[By: Amy Lean MacArthur and Robert A. MacDonald, 2024]

Abstract

In a world increasingly concerned about resource-depletion and environmental degradation, the idea of sustainability as a business strategy has garnered considerable attention. Using the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework, this paper seeks to demonstrate how sustainability, and particularly in approaches informed by Scripture, may be positioned as a strategy in support of organizational mission, vision, and values. Discussions are presented to provide business practitioners, especially Christians, insights on practical strategies to deliver sustainability objectives. We conclude that the pursuit of shalom will entail sacrifices that ultimately bear witness to a stewardship that brings glory to the Creator.

Introduction

The concept of strategy in the context of business has evolved over time. Drucker (‘70s) considered strategy representative of the overarching answer to the questions of “What is our business, what should it be, [and] what will it be?”1 In the 1980s, Porter defined “the essence of strategy formulation [as] coping with competition” and famously proposed an analysis of industry competition built around five basic forces.2 Contemporary definitions of strategic management emphasize the “pattern of positions that the firm seeks out or creates for itself in its competitive environment,”3 and emphasize a resource-based view of the firm advanced by theorists like Barney who stressed the importance of leveraging firm resources for the derivation of competitive advantage.4 Integrating an internal resource-based view (what do we have?) with an external industrial organization perspective (what does the market need?),5 shapes a perspective that considers organizations to be dynamic open systems wherein resources (drawn from the external environment) are transformed and deployed (within the internal environment) and products, services, ideas, etc., are released (into the external environment).

Due to the constant interactions across a firm’s environments, strategy cannot exist in isolation from a firm’s fundamentals. It needs to align with the company’s mission and vision.6 While organizational mission (or purpose) has sometimes been used interchangeably with vision and values, each plays a distinct role within an organization. A mission statement reflects what a business does and why it exists. A vision statement articulates a desired future state.7 This “today/tomorrow” perspective is shaped by values, i.e., “stable, evaluative beliefs that guide our preferences for outcomes or courses of action.”8 Mission, vision, and values will inform strategic formulations that determine what activities will, or will not, be pursued by the firm.9

As an example, the mission statement of Chick-fil-A is “To be America’s best quick-service restaurant at winning and keeping customers,”10 whereas its vision is “To glorify God by being a faithful steward of all that is entrusted to us. To have a positive influence on all who come into contact with Chick-fil-A.”11 These reflect the values of the firm’s founding leadership, which are articulated as “We’re here to serve. We’re better together. We are purpose-driven. We pursue what’s next.”12 Collectively, the firm’s strategy is to emphasize customer service and the provision of a limited though quality product, while recognizing the significant pressures in its competitive environment.13

Sustainability from a Missional Perspective

The term “sustainability” originates in the Latin sustinēre, meaning to maintain, to support, or to endure.14 In business it is used to describe the renewal of various organizational components associated with the firm’s survivability and success.15 The concept emphasizes extended time horizons, such as in reference to “systems and processes that are able to operate and persist on their own over long periods of time.”16 Stead and Stead note that to be sustainable entails “a firm’s ability to continuously renew itself in order to survive over the long term.”17 Often this renewal is described in terms of social transformation, ecological protection, and corporate governance. Ruiz-Mallen and Heras offer that sustainability can be pursued “based on the reciprocal relationship between the environment and the tandem society-economy that supports economic growth.”18

Common to these perspectives is the idea that sustainability is a long-term strategic objective achieved through a culture of consistent stewardship of resources to promote stakeholder (human and environmental) flourishing. Sustainability is an important aspect of strategy as it not only focuses on optimizing the well-being of the external world around the organization, but also helps optimize processes within the organization to operate better.19 Understandably, this optimization is often the catalyst for competitive advantages through innovation and cost reduction. In fact, research demonstrates that “the most sustainable companies are also the most profitable.”20 The caution here is that a firm might be accused of “green washing” (being missional in word only) if sustainability strategic initiatives are not congruent with the firm’s mission and values.21 On the other hand, strong leadership in the cultivation of a culture of sustainability can result in “innovative sustainability solutions, which produce win-win-win outcomes for the environment, society and firms.”22

Galpin et al. consider sustainability to be the most significant strategy of the 21st Century, submitting that “the phrases sustainability, corporate social responsibility, corporate social performance, going green and the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) all refer to organizations enhancing their long-term economic, social and environmental performance.”23 Many corporations seem to corroborate this claim, with over 92 percent of the largest firms posting a corporate social responsibility report annually.24 In their 2009 survey of corporate thought leaders, Berns et. al. found that when it came to the principal benefit of adopting sustainability as a strategy, respondents identified a “broad continuum of rewards that were more grounded in value creation––particularly sustainability’s potential to deliver new sources of competitive advantage.”25 Indeed, the connection between firm performance and sustainability as a strategy is well documented, as the latter can serve as a vehicle to provide “long-term value to both the company and society,” provided that it is “integrated… in a way that complements the firm’s goals and overall mission.”26

The concept of environmental sustainability in business practices has garnered considerable attention in recent decades, given society’s growing focus on matters of the physical environment. The concern about negative impacts of human activity on the environment has translated into calls upon businesses to take responsibility to help reduce any negative impacts.27 Stead and Stead posit that sustainable strategic management processes “are economically competitive, socially responsible, and in balance with the cycles of nature,”28 de-emphasizing the short-term (given that natural processes take time) and encouraging a holistic stakeholder approach (emphasizing both profitability and social responsibility). This is commonly referred to as the TBL and highlights the interrelationship between economic, ecological, and social (or profit, planet, and people) factors.29 Table 1 summarizes the key components of this framework and Figure 1 conceptualizes it in a Venn diagram.

The economic factor, often referred to as profit, describes the economic performance and success of the organization, the element that not only provides returns to shareholders but also oversight through corporate governance. Strategies related to competitive advantage and economies of scale tend to be the focus when an organization’s purpose is profitability or return on assets.

The ecological or planet factor describes the practices of organizations that seek ecological protection and pursue planet-focused strategies that “[integrate] environmental thinking into supply chain management, including product design, material sourcing and selection, manufacturing processes, delivery of the final product to the consumer, and end-of-life management of the product after its useful life.”31 Purposeful planning to limit harmful chemical usage, reducing the distance that products and raw materials travel within the value chain, and using recyclable materials in production are top of mind when seeking to improve environmental health.

The third factor is the social or people element which references the firm’s commitment to social responsibility, particularly its impact on the community. “Product or process-related aspects of operations that affect human safety, welfare, and community development are objectives articulated within a people-focused bottom line.”32 An organization that considers its societal impact concerns itself with justice and equity issues, consumer affordability, and the holistic health of all its stakeholders.

The TBL framework suggests that sustainable practice equates to positive impact while the reverse implies a negative impact. The integration of profit, people, and planet factors can lead to sustainability that “can be characterized as socially desirable, economically viable, and environmentally sustainable development of society.”33 A strategy of sustainability so defined can lead to positive long-term outcomes not only for the firm, but for all stakeholders as well.

The UN Commission on Sustainable Development, established in 1992, has developed several goals with respect to sustainability, which include working to prevent climate change, conserving oceans and marine resources, and protecting, restoring, and promoting the sustainable use of the earth.34 It is worth noting, however, that the Commission’s goals were not founded on a biblical view of reality, nor do they express “the importance of spirituality and agreement upon fundamental, absolute moral principles.”35 In other words, they are not articulated so as to suggest an underlying understanding of a sovereign originator of all creation. How might strategic sustainability be understood theologically? We will address this question next.

Biblical Strategic Sustainability

Understanding why and how sustainability initiatives create value from God’s perspective requires an understanding that sustainability rightly construed reflects a right relationship with God. As noted by Schaeffer, healing between humanity and nature can only result once humanity’s relationship with God is healed.36 Only when humanity rightly understands how the Creator values creation will it seek to value it similarly. A useful approach to a biblical understanding of sustainability is from the perspective of creation care (i.e., care of and for the physical environment and humankind). Genesis 1 presents God creating a world that is intrinsically good because he pronounces it so. Further, God values his good creation, as demonstrated by his ongoing care for it. Contrary to the perspective of deism, God remains involved in what he has made and makes provision for its ongoing existence (Ps. 104:13-14). He has promised all living creatures the freedom from destruction by flood (Gen. 9), built his wisdom into creation (Ps. 19), and articulated his will to redeem all he has made when Christ returns (Rom. 8:19-21).37 Clearly God values creation.

Included in God’s creation are human beings, which in addition to being uniquely made as the imago Dei (Gen. 1:27), are also given a unique responsibility––to exercise dominion over God’s world (Gen. 1:26, 28). The exercise of dominion, given the value God places on creation, invites not destructive exploitation, but rather caring cultivation in keeping with the role of a gardener.38 Schaeffer observes that, “When we have dominion over nature, it is not ours… It belongs to God, and we are to exercise our dominion over these things not as though entitled to exploit them, but as things borrowed or held in trust, which we are to use realizing that they are not ours intrinsically.”39 This describes a stewardship responsibility, whereby human beings are from the beginning charged with the task of managing something that they do not own.

Several conclusions can be made. First, the stewardship responsibility extends not just to individuals, but to human communities as well (and thus corporations). Second, it calls for a response that is neither creation worship (biocentrism), nor exploitation (anthropocentrism), but a God-pleasing, responsible use of the creation (theocentrism). Lastly, there are limitations placed on humans with respect to the personal benefit to be derived from the management of God’s world––the Divine owner intends that the development of creation should contribute to the flourishing of all, not just some, of humanity.40

Humans are not only charged with ecological stewardship, but also with a biblical responsibility to love both God and neighbor. In Mt. 22:37-40 Jesus explains that after loving God with all of one’s heart, soul, and mind, the second great commandment is to love one’s neighbor as oneself. According to Stott, a theocentric understanding of creation considers this commandment to be “a noble calling to cooperate with God for the fulfillment of his purposes, to transform the created order for the pleasure and profit of all. In this way our work is to be an expression of our worship, since our care of the creation will reflect our love for the Creator.”41 In this regard, businesses can create “goods that are truly good and services that truly serve”42 and in so doing demonstrate love of neighbor.

Care for the physical environment can also be understood as an expression of love for neighbor, because the maintenance and preservation of creation seek not only to improve conditions for others in the here and now, but also for those who will come afterward––neighbors displaced by time.43 Moreover, preserving creation for the benefits of neighbors might also be considered a matter of justice. By his commandments to Israel regarding the need to let fields rest every seven years (Ex. 3:20; Lev. 25:1-7) and his protection of animals from the destruction of a catastrophic flood (Gen. 6:19-7:4), God demonstrated that the resources of creation should be sustained for the future so as to provide for subsequent generations. Business activities involving the use of creation today should thus be undertaken with tomorrow in mind, for the benefit of those not yet born.44

Ultimately, sustainability might be considered as partaking fully in God’s intended design for all of life, i.e., a state in which human beings experience the full meaning of shalom (physical, emotional, spiritual, social, individual, communal, and systemic).45 Shalom embodies God’s redemptive mission, signifying “wholeness, health, peace, welfare, prosperity, rest, harmony, and the absence of discord.”46 Working toward this kind of flourishing is to participate in God’s redemptive effort in the world. It should be considered a fundamental motivation for human behaviour.47

Shortt explains that the Hebrew word shalom (typically translated as ‘peace’) is presented in the Bible as “a rich, full and positive concept… [which] signifies wholeness, completeness, integrity, soundness, community, connectedness, righteousness, justice and well-being.”48 As an idea shalom predates Aristotle and describes a state of human flourishing and the common good, as can be seen in Jeremiah’s call to his exiled readers to seek the shalom of Babylon, for in so doing they would find their own shalom (Jer. 29:7). This is not a call to withdraw from the world, but rather to adopt a posture of engagement, working for the good of all and in so doing bring glory to God.49 Wolterstorff argues that shalom is relational in nature, “to enjoy living before God, to enjoy living in one’s physical surroundings, to enjoy living with one’s fellows, to enjoy life with oneself.”50 The ideal is thus one of “persons in relation to one another, persons in relation to the otherness of the physical creation, and persons in relation… to the Transcendent Other, to God, whether or not he is acknowledged by all and whether or not he is even explicitly mentioned.”51 Thus, an organization embracing a mission of shalom might pursue a strategy of employee engagement that provides good work, work that identifies an individual’s talent (e.g., problem-solving, designing, leading, etc.) and coordinates it in a way that not only utilizes but also develops the employee’s gifts.

Another way that sustainability practices create value from God’s perspective is by pursuing good wealth – income that is distributed justly, and not solely for the enrichment of owners. As Naughton suggests, “Profit is like food. We need it if we are to be healthy and sustained in life, but we ought not to live for it. It is a means, not an end; a reward, not a motive.”52 Wealth should not be seen as a source of identity or security, but rather as a tool to be employed in the promotion of flourishing for all stakeholders.

As stewards, humans are meant to care for creation in accountability to and in reverence of God, their creator.53 Stevens defines it as an act of servant leadership which combines the aspects of service to God with managing what he has provided. The fact that the Creator has entrusted the nonhuman portions of creation to humankind represents a significant act of trust within an accountable relationship.54 Business leaders are reminded that they are entrusted with that which should be used for God’s purposes, and their sustainability efforts must be holistically focused, not simply to maintain the human but rather the overall natural order.55 In light of this holistic approach, Van Duzer suggests a framework for how Christians should conduct business: (1) the purpose of the business is to serve, (2) its practice should be to operate sustainably and, (3) it should partner with other organizations in a concerted effort to pursue the common good.56 Strategically, Christian business leaders should pursue products and services that benefit communities (internal and external), promote human flourishing by engaging God-given skills in meaningful work, and ensure justice through the use of accumulated wealth.

Similarly, Stuebs and Kraten address sustainability and social responsibility as a godly calling for all managers, noting that “each manager must build a sustainable business (and, by extension, a sustainable life) on the foundation of a sustainable relationship with God.”57 Therefore Christian businesses ought to be involved in strategic activities of protection, restoration, and transformation, recognizing that while faithful environmental stewardship may not always pay economically, there are other metrics that are important, including the well-being of neighbors (in a universal sense), and that environmental stewardship should be seen as “an extension of the Great Commandment” of Mt. 22:37-40.58 Salgado reminds us that strategy is dependent upon “the leaders’ presuppositions about nature, the world, and the way things work…it depends on the outworking of their worldview.”59 Therefore, the Christian worldview is the identifier that separates biblical strategic sustainability from its secular counterpart. As Oliver states, “The worldly CSR company does good for the world’s sake. The Christian business leader credits God as the source, inspiration and power behind the business results.”60

A Framework for Biblical Strategic Sustainability

Within the TBL framework, in what ways would adherence to biblical strategic sustainability (e.g., a vision of shalom) shape business practices? We return to the TBL conceptualization depicted in Figure 1 and draw attention to the areas of intersection between the three factors:

- Bearable (People-Planet Intersection): operations with focus on social and environmental impacts.

- Viable (Planet-Profit Intersection): operations driven by environmental and economic goals.

- Equitable (Profit-People Intersection): operations with emphasis on economic and social outcomes.61

This tripartite classification presents a possible deficiency, i.e., it is unlikely that a responsible business would strategically choose to frame its mission to completely exclude one of the three principal goals (i.e., people, planet, profit). Would a firm, for example, that falls within the “bearable” enclave operate in such a way that works to deliver ecological and social goals to the exclusion of economic consequences? This omission is even more glaring given the Christian understanding of mission within the context of biblical strategic sustainability.

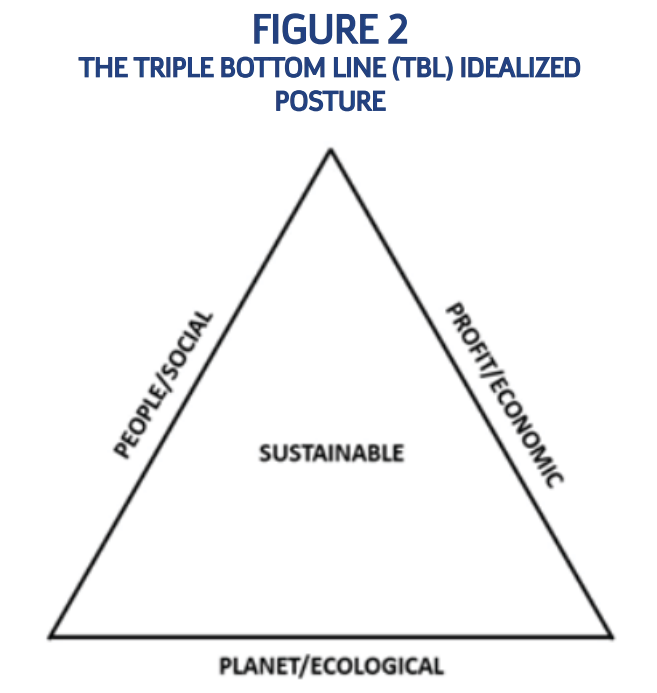

We present a modification to this conceptualization in the Venn diagram by engaging a triangle where each side represents a principal TBL metric (people, planet, or profit). In Figure 2 an equilateral triangle is used to portray a wholistic approach to sustainability as mission. From a biblical worldview it would represent a firm fully devoted to the principles of shalom, where economic, social, and environmental considerations promote long-term sustainability by caring for God’s creation to serve both present and future generations, and the responsible use of resources in a way that allows all life to prosper.62 This visualization suggests that any trade-offs between profit, people, and planet would represent a less than perfect stewardship in the sense that it would not fully meet the requirements of the biblical trusteeship as presented in previous discussions.

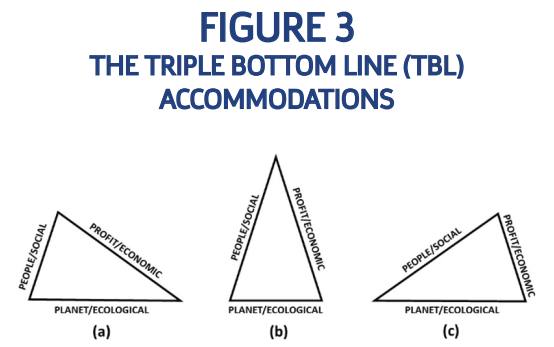

In reality the ideals of shalom are a challenge to business operators. Per Gen. 3, physical and spiritual death (i.e., separation from God) became a fundamental human condition, as the infection of sin passed to all of humanity (Rom. 5:12, 19).63 People thus suffer from depravity which impacts social structures and communities (i.e., the people factor), including the business community.64 Sin has also resulted in an unhealthy individualism, whereby it makes one increasingly self-centered and self-seeking and thus invites conflict that arises out of misplaced passions (e.g. James 4:1-2).65 Because of the Fall, most firms’ practical outcome in pursuit of sustainability will not reflect a perfect triangle, but rather isosceles or scalene relationships.

Human sin has had catastrophic effects on every aspect of the TBL. In addition to its negative impact on the people factor, it can also result in an overemphasis on profit at the expense of other goals. This is in contrast to what the Apostle Paul says in Phil. 2:3-5 when he calls for Christians to seek not only their own interests, but also the interests of others.66 With respect to the physical environment, besides greed-driven resource depletion, human sinfulness resulted in the earth being cursed (Gen. 3:17-18), such that the created order would no longer function in the same way as God had originally designed (Rom. 8:19-22).67 The impact of the Fall has been far reaching and devastating, and thus we must envision a realistic approach to sustainability that is less than perfect.

Figure 3 illustrates three examples of approaches that better depict the reality of business practice from a TBL perspective. Figure 3a represents an organization pursuing environmental and profitability goals at some social cost. Consider, for example, a firm that employs “cleaner” and more efficient technologies in the pursuit of economic success, but these efforts result in redundancy and necessitate a corresponding reduction in headcount. This would not necessarily imply that management is unconcerned for its employees. Rather, the layoffs are a natural, though unfortunate, outcome of the conscious pursuit of reasonable planet and profit goals. This reflects the strategy undertaken when luxury parka manufacturer, Canada Goose, made the decision to lay off seventeen percent of the company’s global corporate workforce. CEO Dani Reiss stated that “the job cuts are meant to put the company in a better position for scaling and will help the Toronto-based business focus on efficiency and key brand, design and operational initiatives.”68 Although the corporation’s commitment to sustainability, the environment, and the community states “we all have an inherent responsibility to give back, protect our planet and make an impact,”69 its strategy to sacrifice jobs to maintain ecological pursuits and increase economic efficiency ultimately threatened its social impact.

Figure 3b represents an organization pursuing economic and social objectives at the cost of negative impacts on the environment. Consider, for example, a company seeking to profitably employ community members in an area that has been economically depressed, perhaps in the harvesting of a natural resource. Natural resource depletion, even in the context of attempts to mitigate negative environmental impacts, could be construed as a cost to the planet bottom line. In eastern Canada, J.D. Irving Ltd. understands that the production of affordable, quality paper products would naturally deplete New Brunswick’s forests. In response it plants multiple trees for each one it cuts down. A company statement relates that “In 2021, we [the firm] planted over 15 million trees on lands we own or manage. This long-term commitment will create a healthy future forest for generations to come.”70 While this arguably represents a decent compromise in the pursuit of the TBL, it is noteworthy that Irving replaces hardwood trees only with softwood species, a perhaps less-than-ideal effort for the ecological objective.71

Figure 3c represents an organization pursuing social and environmental factors at some expense of the firm’s profitability. For example, envision a not-for-profit organization seeking to develop sustainable agriculture in support of a community. Profitability is not a priority as the emphasis will be placed primarily on the positive impacts on people and planet. In the commercial realm, ice cream maker Ben & Jerry’s, a subsidiary of U.K.-based Unilever, has historically placed a significant emphasis on social and environmental causes. At times this stance has served to compromise sales and irritate investors, impacting profitability and investor returns. Yet some have considered this an acceptable, and even desirable reflection of company values.72

The recognition that accommodative actions might be required in the pursuit of a TBL strategy is not to suggest that the shalom ideal should be abandoned. It is a reflection that, in a broken creation, nothing can be rendered perfectly. As Wong and Rae note, there will be trade-offs when Christians pursue sustainable practices. For example, social and environmental protection often require a financial investment or an avoidance of practices that offer positive short-term returns.73 Sacrifice is a concept that Christians should understand. As Jesus notes in Mt. 10:39, it is through sacrifice that one may ultimately find life. This is also what we are called to do as Christian business practitioners––“to build a sustainable business on the foundation of a sustainable life with God.”74 When business strategies implemented by Christians reflect both the idealism of shalom and the sacrifice necessary for its pursuit, decisions made with respect to the stewardship of people, planet, and profit will bear witness to our sacred trusteeship from God.

Conclusions

While sustainability can be considered a viable business strategy as demonstrated through approaches like the TBL, Christians would understand that it also portrays the relational expectations of our Creator God. Shortt relates that human beings were “created for right relationships, relationships with our fellow human beings, with our physical environment and supremely with God.”75 While these relationships have been fractured (and continue to be fractured) by human sinfulness, Christ came to restore what has been broken through his atoning death and resurrection. His ultimate sacrifice ushers in a “kingdom of shalom which is both now and not yet.”76 To pursue sustainability in the context of business is to pursue God’s kingdom of shalom. The fact that these attempts––even with the best intentions––may fall short need not be considered as a surrender to secular pragmatism. Instead, these shortfalls may be construed as necessary sacrifices in a fallen world. The ideal is preserved in those sacrifices that can ultimately bear witness to a God-given trusteeship with regards to people, planet, and profit.

About the Authors

Amy Lean MacArthur is Assistant Professor in Business Administration and head of the Marketing concentration at Crandall University, New Brunswick, Canada. Amy also serves as the university’s Strategic Communications Specialist. Her research interests are in communication, student engagement, transformational learning, and mentorship. Her recent publication, Thriving in First Year Higher Education Settings, a chapter in Wellbeing in Higher Education Settings (edited book), is available through Emerald. Amy recently presented at the International Conference on Educational Leadership and Management in Jamaica. In addition to her academic work, she and her husband own and operate commercial buildings in their hometown.

Robert A. MacDonald holds the Stephen S. Steeves Chair in Business and is Professor of Business Administration at Crandall University, New Brunswick, Canada. Robert’s research is focused on case study development, faith integration in business, strategic management, human resource management, and the governance of not-for-profit organizations. His past projects, publications, and presentations stem from research into municipal policy, not-for-profit governance and control, charitable giving among Canadians, and challenges faced by small business enterprises. His work has appeared in several publications including the Christian Business Academy Review, the Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, the Case Research Journal, and Accounting Perspectives. Robert is a member of the North American Case Research Association (NACRA) and the Christian Business Faculty Association (CBFA) and serves on the editorial board of the Case Research Journal.

Notes

1Peter F. Drucker, An Introductory View of Management, (New York: Harper’s College Press, 1977): 115–118, 467.

2Michael E. Porter, “How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy.” In Strategy: Seeking and Securing Competitive Advantage, edited by Cynthia A, Montgomery and Michael E. Porter (Boston: HBR Books, 1991): 11. Porter defined these forces as industry competition, threat of new entrants, bargaining power of suppliers, threat of substitute products or services, and bargaining power of suppliers.

3Patrick C. Woodcock and Paul W. Beamish, Concepts in Strategic Management (6th Edition). (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 2003): 2.

4Jay B. Barney and William S. Hesterley, Strategic Management & Competitive Advantage. (Upper Saddle River: Pearson, 2018).

5Tanya Sammut-Bonnici, “Strategic Management.” In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management, edited by C.L. Cooper, M. Vodosek, D.N. Harog and J.M. McNett, (2015), 1.

6Jake Brereton, “Understanding the Distinctions: Vision, Mission, and Strategy,” LaunchNotes Blog, https://www.launchnotes.com/blog/understanding-the-distinctions-vision-mission-and-strategy, February 1, 2024.

7“What is the difference between mission, vision and values statements?” [n.d.], https://www.shrm.org/topics-tools/tools/hr-answers/difference-mission-vision-values-statements.

8S.L. McShane, S.L. Steen, and K. Tassa, Canadian Organizational Behaviour (9th ed.). (Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 2015): 348.

9Principles of Management (OER). (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2010).

10Armand Gilinsky, Business Strategy for a Better Normal. (Cham: Palgrave, 2023): 5.

11Larry S. Julian, God is my CEO: Following God’s Principles in a Bottom-line World. (New York: Adams Media, 2002): 213.

12Chik-fil-A, “Purpose,” https://www.chick-fil-a.com/careers/culture

13Julian, 216.

14Margaret Robertson, Sustainability Principles and Practice. (New York: Routledge, 2017): 3.

15Edward W. Stead and Jean Garner Stead, Sustainable Strategic Management (New York: Sharpe, 2004): 6.

16Margaret Robertson, 3.

17Stead and Stead, 6.

18Isabel Ruiz-Mallen and Maria Heras, “What Sustainability? Higher Education Institutions’ Pathways to Reach the Agenda 2030 Goals,” Sustainability,12 (2020), 3.

19“The Importance of Sustainability in Business,” Vanderbilt + UBC, https://business.vanderbilt.edu/corporate-sustainability-certificate/arti…, December 20, 2023.

20Natalie Chladek, “Why You Need Sustainability in your Business Strategy,” HBS Online Business Insights blog, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/business-sustainability-strategies, November 6, 2019

21Timothy Galpin, J. Lee Whittington, and Greg Bell, “Is your sustainability strategy sustainable? Creating a culture of sustainability,” Corporate Governance, 15 (2015): 1-17.

22Ibid.

23Ibid, 1.

24Will Oliver, “The Quadruple Bottom Line,” Center for Christianity in Business, No. 9 (Fall 2020), 52-60; https://hc.edu/center-for-christianity-in-business/2023/06/08/the-quadruple-bottom-line/, June 8, 2023.

25Maurice Berns et al., “Sustainability and Competitive Advantage,” MIT Sloan Management Review, 51 (2009): 23.

26Galpin et al., 7.

27Robertson, 6. These include calls to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, reduce waste, etc.

28Stead and Stead, 36

29Anastasia Dalibozhko and Inna Krakovetskaya, “Youth Entrepreneurial Projects for the Sustainable Development of Global Community: Evidence from Enactus Program,” SHA Web of Conferences, 27 (2018): 3.

30Kelsey Miller, “The Triple Bottom Line,” HBR Business Insights Blog, https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/what-is-the-triple-bottom-line, December 8, 2020.

31Hannah Stolze, Wisdom-based Business (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2021): 164.

32Ibid, 63.

33Dalibozhko and Krakovetskaya, 4.

34Cafferky, “Sabbath: The Theological Roots of Sustainable Development,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 18 (2015): 42–45.

35Ibid.

36Francis A. Schaeffer, Pollution and the Death of Man: The Christian View of Ecology, (Wheaton: Tyndale, 1970).

37Kenman L. Wong and Scott B. Rae, Business for the Common Good: A Christian Vision for the Marketplace (Downers Grove: IVP, 2011): 237¬–237.

38Richard C. Chewning, John W. Eby, and Shirley J. Roels, Business Through the Eyes of Faith (San Francisco: Harper, 1990): 217–219.

39Mark B. Spence and Lee W. Brown, “Theology and Corporate Environmental Responsibility: A Biblical Literalism Approach to Creation Care,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 21 (2018): 50-51. The authors quote Francis Schaeffer’s Pollution and the Death of Man.

40Wong and Rae, 233. The authors helpfully define anthropocentrism as the belief that creation exists only for the benefit of humans and biocentrism as the belief that creation has value because it consists of living things, not because of its creator. Theocentrism is presented as a Christian approach to creation, with value being derived from the Creator.

41Wong and Rae, 250. The authors quote John Stott’s The Care of Creation.

42Michael Naughton, “The Loss of Wisdom in the University and the Perils of Business Education: Recovering Practical Wisdom Through the Integration of Liberal and Professional Education,” Christian Scholar’s Review, https://christianscholars.com/the-loss-of-wisdom-in-the-university-and-the-perils-of-business-education-recovering-practical-wisdom-through-the-integration-of-liberal-and-professional-education/, June 8, 2024.

43Ibid.

44Chewning et al., 228.

45Wong and Rae, 74.

46Ibid, 72.

47Jonathan T. Pennington, “A Biblical Theology of Human Flourishing,” The Institute for Faith, Work & Economics, (2015):1–2.

48John Shortt, “Is Talk of Christian Education Meaningful?” In Christian Faith, Formation and Education, edited by Ros Stuart-Buttle and John Shortt (Cham: Palgrave, 2018): 37.

49Ibid. Jeremiah’s call is ultimately to work for the common good.

50Ibid, 38. The author quotes Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Educating for Life: Reflections on Christian Teaching and Learning.

51Ibid, 39.

52Naughton.

53Jeff Van Duzer, Why Business Matters to God (Grand Rapids: IVP, 2010): 66-69.

54R. Paul Stevens, “Stewardship,” The Market Ministry Handbook, edited by R. Paul Stevens and Robert Banks (Vancouver: Regent, 2005): 232-238.

55Van Duzer, 66-69.

56Ibid, 151-163.

57Marty Stuebs and Michael Kraten, “Solomon’s Lessons for Leading Sustainable Lives and Organizations,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 24 (2021): 61-71.

58Wong and Rae, 250.

59Leo Salgado, “How a Christian Worldview Defines Strategy,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 14 (2011): 1-15.

60Oliver, 4.

61Dainora Jociute, “The Triple Bottom Line Framework,” Viima Blog, https://www.viima.com/blog/triple-bottom-line, October 20, 2022.

62Cafferky, 42–45.

63Augustus H. Strong, Systematic Theology: A Compendium, (Valley Forge: Judson, 1979): 590–593.

64Ibid, 637.

65Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology, (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1985): 618.

66Ibid, 619.

67Simon Turpin, “Five Effects of the Fall in Genesis 3,” Answers in Genesis Blog, https://answersingenesis.org/blogs/simon-turpin/2016/06/27/five-effects-of-the-fall-in-genesis-3/, June 27, 2016.

68Jenna Benchetrit, “Canada Goose is laying off 17 per cent of its global corporate staff,” CBC News Business, https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-goose-layoffs-1.7155797

69Canada Goose, “Sustainability,” https://www.canadagoose.com/ca/en/sustainability/

70J.D. Irving, Limited, “Irving Woodlands,” https://irvingwoodlands.com/jdi-woodlands-about-faq.aspx

71Ibid.

72Shann Biglione, “Why Ben & Jerry’s Activism Didn’t Drive Unilever’s Ice Cream Split,” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/shannbiglione/2024/04/08/why-ben–jerrys-activism-didnt-drive-unilevers-ice-cream-split/

73Wong and Rae, 230-250.

74Stuebs and Kraten, 61.

75Shortt, 38.

76Ibid.