Brand and Celebrity Worship:

Confronting Biases Underlying Business Idols

[By Cora Barnhart]

Abstract

A predisposition to idolatry influences decision-making in all facets of life, including business. This article examines how and why idolatry underlies contemporary business practices, whether through well-known pursuits of money, acceptance, and fame, or alternative forms of idolatry such as brand identity and celebrity CEOs. The article develops a biblical framework that connects humanity’s inherent need to worship something to God’s original purpose for humanity and how the Fall distorted that purpose. The article then analyzes the first two commandments and the Israelites’ challenges with idolatry, identifying two critical consequences for business. First, individuals and organizations often mirror the shortcomings of the idols they worship. Second, becoming enslaved to an idol comes at the price of losing freedom. The paper considers how organizations capitalize on the desire to belong and the culture around influencers to attract followers. It then summarizes how cognitive biases amongst leaders parallel Scriptural warnings against wealth accumulation, self-promotion, and other behaviors that stem from the pursuit of idolatry. It concludes by offering a model for business leadership that is based on humility. It emphasizes transparency, accountability, and subdued individual discretion as safeguards against biases that compromise long-term value and integrity.

Introduction

In 2014, the small start-up Theranos appeared to have struck gold when it developed a process that required only a few drops of blood to perform over 1,000 medical tests.1 Over the previous eleven years, Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes had raised millions in seed capital and secured a $50 million deal with Walgreens to open wellness centers inside Walgreen stores featuring Theranos’ technology. Holmes also actively promoted her image, dressing in black turtlenecks, drinking green juice, and adopting other mannerisms that reinforced the media’s fawning perception of her as the next Steve Jobs.2 The company was valued at $9 billion, netting Holmes a personal worth of $4.5 billion. Four years later, the company collapsed after the much-hyped technology was exposed by the Wall Street Journal to be a sham. Holmes was convicted of four counts of defrauding investors and sentenced to eleven years in a federal prison in 2023.3

How could Walgreens and the seasoned investors in Theranos be fooled?4 Their previous professional successes likely contributed to the blatant lack of diligence in their due diligence process. Exclusive access to a seemingly lucrative project touted by luminaries and fellow billionaires increased the allure. Finally, there was the “hurricane of self perpetuating hype” that amplified Holmes’ celebrity CEO image.5

The preoccupation with wealth, acceptance, and fame underscores many instances of idolatry in the marketplace. The Theranos saga highlights some new enablers of idolatry in business – the worship of brand and the celebrity status of successful business leaders. This article hypothesizes that the creation of these and other idols in the marketplace stems from an inherent human need to worship someone or something. These ill-conceived pursuits inevitably mislead stakeholders and result in ruinous consequences.

We begin by reviewing idolatry’s connection to God’s first two commandments. Examining idolatry’s destructive impact on the Israelites’ relationship with God reveals two concerns critical for business. First, idols’ dysfunctions are often mirrored by the individuals and organizations that worship them. Second, idolatry inevitably results in a loss of freedom. We draw parallels between modern day marketplace celebrities and Old Testament leaders where self centered pursuits of wealth and influence, and their preoccupation with worshipping the creation instead of the creator, often lead to cognitive biases in decision making which cost the organization in the long run.

Idolatry in Business

“You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself an image in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below” (Exodus 20:3-4).

Idolatry is not limited to worshipping ancient pagan gods or graven images. Martin Luther argued that obeying the first commandment requires recognizing that “upon which you set your heart and put your trust is properly your god.”6 One way to recognize the worship of a false god is that it has replaced the Creator God as “whatever your heart clings to or relies on for ultimate security.”7 In banning the creation of an image which is believed to possess divine power, the second commandment established a distinction between the Creator and His creation. Imagining an image is somehow connected to God would distract humans “from God’s true being.”8

Even for committed Christians, the temptation to treasure God’s creation over the Creator indicates that a range of areas of life are vulnerable to idolatry. Keller identified money and success as being among the “surface idols” many are tempted to rely upon to amass power, security, a sense of belonging, and other “underlying idols.”9 Thomas Aquinas argued that human decisions are subconsciously driven by the pursuit of money, power, pleasure, fame, and 3 things that are not inherently corrupt but could become idols once obtaining them becomes the ultimate goal.10 The appeal of these idols is apparent in media messages that encourage consumers to indulge themselves or that fawn over charismatic CEOs and influencers with a multitude of followers.

Aquinas warned that choosing “substitutes for God” would not “satisfy the craving for happiness.”11 One reason that pursuing success, money, and other false idols leaves people empty is that they are positional goods.12 Amassing them leads to social comparison and people can never acquire enough to feel fulfilled. This pursuit can lead to objectification, defining someone in terms of success, power, or other “enviable characteristics.” Sometimes individuals self-objectify, defining themselves in terms of their wealth, achievements, or other worldly rewards that leads to hubris, or pride. Pride is particularly problematic. Saint Augustine observed that unlike other vices, pride hides in good things and, per Aquinas, it results in misery.13

Imagery in Creation and Idol Worship

Imagery in Creation carries an important message: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27). Also, in Isaiah, “Bring my sons from afar and my daughters from the ends of the earth—everyone who is called by my name, whom I created for my glory, whom I formed and made” (43:6-7). These passages make two important points: God created human beings in His image to glorify Himself – so that the world would be filled with reflectors of God, and “to display the original — to point to the original, glorify the original.” 14

In what ways are humans to display the original? The opening chapters of Genesis indicate that creation and work were among the avenues through which God intended humans to display His glory. Genesis 1:31 (“And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day”) recognizes God as the creator of work and the goodness inherent in work. His purpose for humanity is apparent in Genesis 2:15 (“The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to work it and keep it”) in that God intended humans to work and take care of His creation. And yet Adam and Eve placed their desire for the forbidden fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil ahead of their obedience to God (Gen. 2:17). An element of “self worship” is evident in the first couple’s conclusion that their need was superior to that of God’s plan.15

The temptation to succumb to false worship is visible in many aspects of business today. Increasingly in today’s culture, there is a desire to connect to big or famous brands, either through owning their products, following those associated with them, or joining the teams that create and manage them. Social media and news outlets reward influencers and leaders who promote the products and services, and who encourage cultural immersions that build devotion and loyalty, in some instances to the point where fans cross the boundary into the realm of “idol worship.”

Idol Worship: Reflecting That Which Surrounds Us

Piper suggests that humans are intentionally designed by God to mirror their environment.16 Scripture makes two observations related to this. First, although God intended humankind to reflect Him, anyone who does not obey Him will reflect and ultimately worship something else in His creation. Followers thus become identified with the idols around them. Psalm 115:8 warns that those who make and love idols will become “as empty and lifeless as the idols they worship.”17

The worship of idols also leads to the loss of freedom. God liberated the Israelites from slavery in Egypt to provide them the freedom to worship him, yet the Israelites sought safety and security from a king instead of God.18 Their 4 desires for security and being like the surrounding nations led them to ask for a king (1 Samuel 8:5). God warned them that supporting a kingdom would result in the king taking their sons, daughters, and money (1 Samuel 8:11–17). The first king, Saul, was a military success, but his pursuit of self-image and security led to two acts of disobedience that resulted in God rejecting him as king.19 Similarly, their next king, David, also succeeded militarily but made numerous missteps.20 David’s reign provided the Israelites with security against external enemies but required them to enlist in the military. Seeking security from a source other than God always comes with a significant cost – the sacrifice of freedom that God has promised.

It may be interesting to cast the reverence consumers afforded Nike, Apple, and other successful brands in light of the Israelites’ experience: “consumers flock to them, competitors fear them,… brands stand immovable and unshakeable, at least they like to think they do.”21 Following a king in the Promised Land and a popular brand share similarities, such as a feeling of significance by being affiliated with an important group, being a part of something that “owns their segment of the market,” and enjoying a connection to something that “casts a large shadow.”22

Social Media and the Power of Access

Idol worshippers expect favors from the deity after they have completed a task or paid a price.23 Joining an exclusive group (such as a brand community) can confer benefits or power, thus enhancing the members’ loyalty. This recognition underscores how organizations change their strategy in attracting new customers. Traditionally, big brands required celebrities to commit to standard endorsement deals, but many now use celebrities’ and other influencers’ social media accounts to promote the brand but also to gain access to the followers.24 Apart from cost savings, this new strategy also lets the organization monitor engagement metrics, including likes, shares, and online conversations, enabling better estimates of the return generated.25 This approach also shortens the engagement period between the influencer and the organization, reducing the exposure for both parties.

The transition from standard endorsement deals to social media campaigns, by placing the emphasis on the number of likes, shares, and follower counts, risks objectifying influencers and leading to harmful social comparisons among followers.26 Failure to examine social media details may result in blindly pursuing accounts with followers who turn out to be unlikely customers.27 Careful background research does not prevent an influencer from going rogue and behaving unprofessionally online.28 Organizations less experienced in using social media promotions may lack quality control mechanisms over transactions and have platforms that are prone to scams.29 Such missteps hurt the brand’s value and risk other, such as reputational, harms as well.

Celebrity CEOs and Kings in Scripture

Attracting followers is an increasingly recognizable aspect of organizational leadership. Customers may “spread the word” and become “committed followers” of those leaders found to be charismatic.30 The phenomenon of the celebrity CEO is born. Although social media and cable TV have amplified the visibility of the celebrity CEO, it is worth noting that Henry Ford, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt were among the most widely recognized business leadership icons in modern history.31

Celebrity CEOs are expected to attract new opportunities for their organizations, including improved brand image, higher stock prices, and elevated morale.32 However, a study by Collins identified “a gargantuan personal ego,” or pride, that can be attributed to the CEOs as a contributing factor in two-thirds of the less successful organizations.33 Despite their organizations’ weak performance, several of these CEOs became celebrities, gracing magazine covers, becoming the subject of popular autobiographies, and receiving massive compensation packages. Their celebrated status also invited opportunities to join other firms’ boards and network with other prestigious leaders. The study concluded that this group of leaders “were ambitious for themselves… but they failed utterly in the task of creating an enduring great company.”34

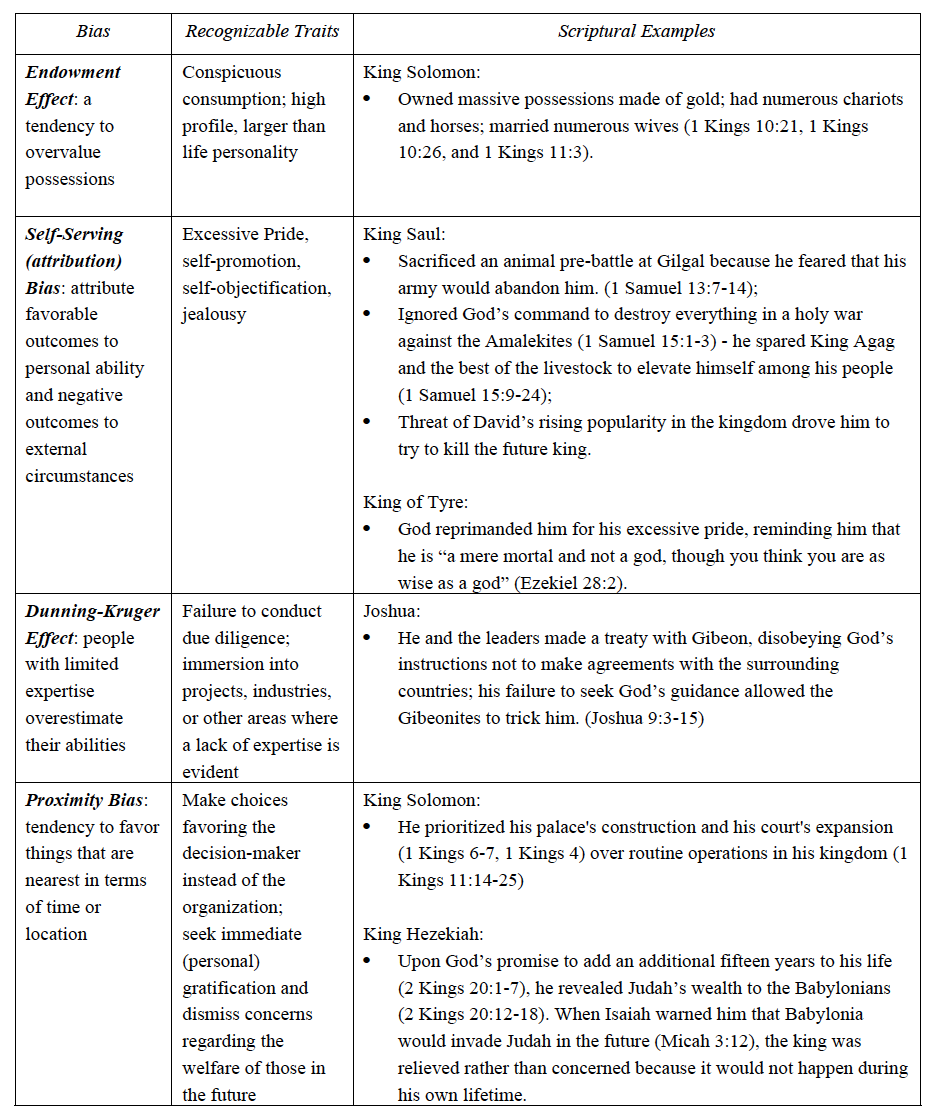

Collin’s study also identified hubris as a cause of an organization’s failure to thrive.35 It manifested in actions such as the pursuit of growth at all costs, plunge into industries where the firm had little expertise, or choices conferring only personal short-term payoffs. Celebrity CEOs who promote themselves at the expense of the organization’s long-term success are hamstrung by behavioral choices that reflect distinctive cognitive biases which also appear to have affected many charismatic leaders in Scripture. Table 1 offers some examples.

Table 1

Biases, Traits, and Examples from Scripture

To discourage the worship of idols manifested in wealth, power, and success, God has expressly instructed in Deuteronomy 17:16-18:

The king, moreover, must not acquire great numbers of horses for himself or make the people return to Egypt to get more of them, for the Lord has told you, “You are not to go back that way again.” He must not take many wives, or his heart will be led astray. He must not accumulate large amounts of silver and gold. When he takes the throne of his kingdom, he is to write for himself on a scroll a copy of this law, taken from that of the Levitical priests.

King Solomon’s vast wealth and many wives blatantly disobeyed these instructions. His foreign wives had him build “high places” so that they could worship their false gods (1 Kings 11:1-10). Despite God’s reprimand twice in dreams, Solomon ignored the warnings. The idolatry reflects a “larger than life” obsession stemming from an endowment effect, which also affects the behaviors of many celebrity CEOs in the postmodern marketplace.

A related bias is the tendency to attribute favorable outcomes to personal ability and negative outcomes to outside circumstances, commonly known as the self-serving or attribution bias. King Saul’s attempt to kill David was very much an act of jealousy as an affirmation of his exaggerated sense of self-worth.36 Ezekiel 28:2 warned another king against falling prey to this idol: “Son of man, say to the ruler of Tyre, ‘This is what the Sovereign Lord says: “‘In the pride of your heart you say, ‘I am a god; I sit on the throne of a god in the heart of the seas.” But you are a mere mortal and not a god, though you think you are as wise as a god.” Pride and self-promotion characterize many CEOs celebrated by the business media, including Holmes.37 Amid the hurricane of media hype, Holmes was featured on magazine covers including Fortune, Vanity Fair, Glamour, and Inc.38

Research suggests that firms that are struggling may be particularly prone to selecting an “outsider CEO” whose celebrity status stemmed from a successful record in an unrelated industry.39 The Dunning-Kruger effect is a cognitive bias that causes those who have enjoyed success in one area to overestimate their abilities in areas that are unrelated to their specialty. Previous ventures celebrated by Walgreens (and its investors) could have made the firm less careful in assessing its partnership with Theranos. The highly respected public figures, such as William Perry, George Shultz, and Henry Kissinger, who sat on Theranos’ board, apparently lacked technical and financial expertise in steering this much hyped new venture. A comparable example in Scripture is Joshua allowing the Hivites to trick him into signing a peace treaty. In spite of the fact that God had prohibited the forming of any alliances with these tribes, the Israelites failed to conduct any due diligence. Their previous successes had made them arrogant and overconfident in their own judgement instead of seeking God’s guidance.40

Proximity biases also tend to hamper a leader’s performance. Organizations may seek out a “high-profile, larger-than-life leader” whose personal ambitions may be at odds with what best serve the company’s long-term interests. Often, leaders give preference to whatever is physically closer or more available, just as King Solomon paid more attention to his palace’s construction and his court’s expansion instead of what was happening in the far-flung corners of his empire.41 King Hezekiah, instead of being concerned with the archenemy’s ulterior intention in spite of Isaiah’s warning (Micah 3:12) when he showed off Judah’s wealth to the Babylonians (2 Kings 20:12-18), would resign to the thought that “will there not be peace and security in my lifetime?” (2 Kings 20:19). Apparently, his own personal safety and well-being in the short run trumped what could happen to the kingdom in the distant future.

Countering Idols in the Postmodern Marketplace

The fact that idol worship in the marketplace leads to decision biases with detrimental implications for business raises the question of what could be a valid spiritual response for faith-driven business leaders. Proverbs 22:4 reminds us 8 that “the reward for humility and fear of the Lord is riches and honor and life.” Humility is the perfect counterweight to hubris and enables a substitute of God-centeredness for “everything else but God-centeredness”! God uses discipline to develop humility in his followers.

Prior successes can shield individuals and organizations from life’s pitfalls and poses the risk of a “success trap.” The trap results from self-serving biases and causes people to forget or misidentify factors that contributed to their success. The pride that develops leaves the individual or organization susceptible to being shaken and possibly devastated by challenges.42 Their lack of resilience means they fear failure and are more likely to address blunders by concealing, disavowing, or defending them.43

One indication of a success trap in an organization is that it develops a culture of fear.44 Signs of fear are often apparent in organizations that have floundered, including Theranos. Doubts about its financial standing or “proven” technology were met by a leadership team that “shut down, ignored, bullied or threatened” those making the inquiries.45Another sign of fear is high employee turnover. Holmes hired highly respected experts in science, advertising, and computer electronics, but many left as Theranos’ leadership began to quash any constructive criticism that they offered.46

Organizations can protect themselves from the success trap through some of the same intentional processes that help individuals develop humility. Humility takes root when we allow others to hold us accountable.47 One way organizations can place an emphasis on accountability and transparency is by evaluating decision-making not only on outcomes but also on the process leading up to them.48 This approach helps an organization become more inclined to perceive failure as the cost of learning rather than something to disguise or dismiss.49

Humility can also counter the Dunning-Kruger effect, narcissism, and other factors that “blind” leaders to perceptions of the world that differ from their own. Research estimates that 5% of the general population and 18% of CEOs possess narcissistic traits, including “a grandiose sense of self-importance, sensitivity to criticism, a sense of entitlement, a lack of empathy, and a need for admiration.”50 Organizations can mitigate the Dunning-Kruger effect and narcissism by cultivating a culture of humility that makes decision-makers more inclined to consider diverse viewpoints.51

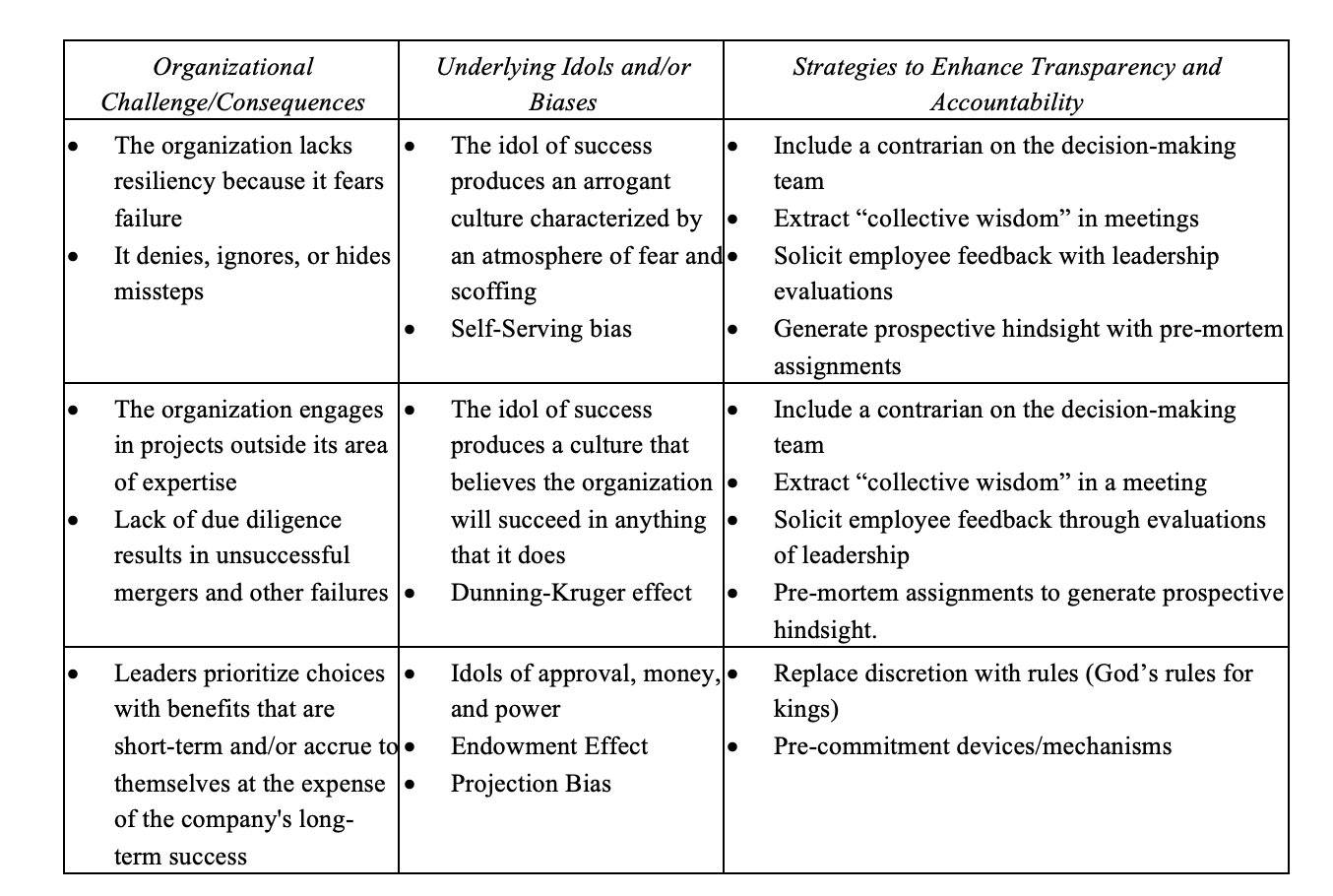

One obstacle imposed by the Dunning-Kruger effect and other cognitive biases is that they are easier to see in others than in ourselves. Jesus warns of this distortion in Matthew 7:3: “Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?” The blindness associated with the pursuit of idols prevents an organization’s leadership teams from readily recognizing them. We highlight some possible strategies to deal with these challenges in Table 2.52

Table 2

Organizational Challenges, Idols or Biases, and Countervailing Strategies

One way to begin the process is to consider whether the environment surrounding the decision-making process tolerates alternative opinions.53 As the case of Theranos shows, fear and intolerance of questions or criticism are signs that success has become an idol.54 Another consideration is whether an optimal decision is likely to result from the decision-making team’s design. God used Samuel, Nathan, and other judges and prophets in the Old Testament to correct kings when they contradicted His will. Likewise, a decision-making team could benefit by adding a contrarian or contrarians to encourage constructive dissent.55 Other ways to avoid a culture of fear in the boardroom include soliciting employee feedback through leadership evaluations and generating prospective hindsight through premortem assignments.56

An emphasis on honesty, accountability, and transparency also helps mitigate tendencies to favor choices that benefit leaders at the expense of the organization’s long-term interests. In addition to the endowment effect, the projection bias that causes leaders to favor things or people closest to them in terms of time or distance also contributes to this preference. Recall that God limited Israeli leaders’ material possessions (Deuteronomy 17:16-18) knowing how susceptible they would be to the idols connected to wealth and pleasure. Similarly, instituting a more “rules-based” approach to decision-making can yield favorable results for organizations. A rules approach should also be easy to understand so that policy deviations are quickly identified.57 Rules reduce inconsistencies in judgments which can be costly in terms of reputation and consequences for organizations.58

Organizations can use commitment devices to limit the discretion of decision-makers. Research shows they are particularly effective to combat the idol of pleasure, as preventative measures to force commitment to a “should choice” now rather than a “want choice” in the future often pay off.59 Commitment devices have been shown successful in helping savers and others to stave off the appeal of immediate over delayed consumption.60

Conclusions

The Fall of mankind (Gen. 3) has distorted humanity’s relationship with success and other good things from the world of business. Instead of putting God in His rightful place, there is persistent temptation for people to worship these objects/achievements as idols. Behavioral biases associated with the worship of these idols, including the self-serving bias, the Dunning-Kruger effect, the endowment effect, and the projection bias, posed the same challenges as what plagued the Israeli leaders in the Old Testament as they do for modern day leaders and stakeholders. In recognizing 10 God’s intention for humanity to mirror His glory, it is worth remembering that, as Richard Lints writes, “A mirror reflects. A distorted or broken mirror also reflects, but in a distorted or broken fashion.”61 The intentional adoption of measures that promote accountability, transparency, and honesty can be effective in battling the distortion that idolatry brings.

About the Author

Cora Barnhart is Professor of economics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Her current research interests include the impact of innovation and creative destruction on the economy and applications of faith in business practices. Prior to teaching at Palm Beach Atlantic University, she served as the editor of the tax section of the Bankrate Monitor, and served on faculties at Florida Atlantic University, Furman University, and Clemson University. She has written several tax and personal finance articles published on websites that include Bankrate, Yahoo, and USA Today. Her academic publications include articles in Economic Inquiry, Public Choice, Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, The Journal of Futures Markets, Sport in Society, Christian Business Academy Review, Journal of Biblical Perspectives in Leadership, and Financial Practice and Education. She holds a B.S. from Francis Marion University and an M.A. and Ph.D. from Clemson University

Notes

1Stella Kleinman, “Elizabeth Holmes: Founder and CEO of Theranos,” in Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Elizabeth-Holmes.

2See Kleinman, “Elizabeth Holmes.”

3See Kleinman, “Elizabeth Holmes.” Also see Erin Griffith, “What Red Flags? Elizabeth Holmes Trial Exposes

Investors’ Carelessness,” New York Times (Nov 4, 2021).

http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/newspapers/what-red-flags-elizabeth-holmes-trialexposes/

docview/2593218461/se-2?accountid=26397. Investors included the Walton family (lost $150 million),

Rupert Murdoch ($125m), the DeVos family ($100m), ex-Defense Secretary Jim Mattis ($85 million), former

Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and New England Patriots owner Robert Kraft

4According to Griffith, “What Red Flags,” an investor invested $6 million even though Holmes failed to produce an

audited financial statement. One investment firm invested $5 million in 2013, despite not understanding the

company’s technologies or its work with the military and pharmaceutical companies it had mentioned. Another

investment professional admitted to not hiring consultants in law, science, or regulatory matters to verify Theranos’

claims.

5Ibid.

6G. K. Beale, We Become What We Worship: A Biblical Theology of Idolatry (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity

Press, 2008).

7Ibid., 17.

8Ibid., 19.

9See Timothy Keller, Counterfeit Gods: The Empty Promises of Money, Sex, and Power, and the Only Hope That Matters (New York, NY: Dutton, 2009).

10Arthur C. Brooks, From Strength to Strength: Finding Meaning, Success, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life (New York, NY: Portfolio/Penguin, 2022).

11Brooks, From Strength to Strength, 71.

12Ibid.

13Ibid.

14John Piper, “Why Did God Create the World?” Desiring God, September 22, 2012. https://www.desiringgod.org/messages/why-did-god-create-the-world.

15Beale, We Become, 134.

16Piper, “Why Did God,” 16

17Beale, We Become, 142.

18Erwin Goodenough, “Kingship in Early Israel,” Journal of Biblical Literature 48, no. 3/4 (1929): 169-205. https://doi.org/10.2307/3259724

19Saul was supposed to wait for Samuel at Gilgal but sacrificed the animal pre-battle because he was afraid his army would abandon him (1 Samuel 13:7-14). In 1 Samuel 15:1-3, God commanded him to wage a holy war against the Amalekites. Rather than obeying God’s instructions to destroy everything, he decided not to kill King Agag or the best of the livestock to elevate his image among his people and offer a sacrifice (1 Samuel 15:9-24).

20He disobeyed God and placed his own priorities ahead of those he was supposed to lead. He committed adultery and planned Uriah’s murder (2 Samuel 11:2-5, 14-17) and called for a census for military draft and taxation purposes (2 Samuel 24:1-4).

21Andy Geers. The Idolatry of Brand Names. coding for Christ at Geero.net October 13, 2008, https://www.geero.net/2008/10/the_idolatry_of_brand_names/.

22Ibid.

23Jason Stansbury, “Sin in Business: Perversion, Defilement, and Idolatry,” Journal of Religion and Business Ethics

5, no. 1 (2022). https://via.library.depaul.edu/jrbe/vol5/iss1/7/.

24Aaron Fronda, “Celebrity Endorsements Focus on Social Media Takeovers,” European CEO. No date.

https://www.europeanceo.com/business-and-management/celebrity-endorsements-focus-on-social-mediatakeovers/.

25Unknown author, “What is Influencer Marketing?” McKenzie & Company, April 10, 2023.

https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-influencer-marketing.

26See Çınaroğlu, M., and E. Yılmazer. “Problematic Social Media Use, Self-Objectification, and Body Image

Disturbance: The Moderating Roles of Physical Activity and Diet Intensity.” Psoriasis: Targets and Therapy, vol.

18, 2025, pp. 931-952. ProQuest, http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/scholarly-journals/problematic-socialmedia-

use-self-objectification/docview/3190904783/se-2 (doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S517193). Also see

Sahin, Elif, and Nevin Sanlier. “Relationships among Nutrition Knowledge Level, Healthy Eating Obsessions,

Body Image, and Social Media Usage in Females: A Cross-Sectional Study,” BMC Public Health, vol. 25, 2025,

pp. 1-14. http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/scholarly-journals/relationships-among-nutrition-knowledgelevel/

docview/3216560809/se-2 (doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22689-1).

27Unknown author, “What is Influencer Marketing?”

28Ibid.

29Andreas Rivera,” What is C2C?” Business News Daily. January 09, 2024.

https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/5084-what-is-c2c.html.

30See Benjamin Galvin, Prasad Balkundi, and David Waldman, “Spreading the Word: The Role of Surrogates in

Charismatic Leadership Processes,” Academy of Management Review 35, no. 3 (2017): 477-494.

https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.3.zok477.

31Janice Edwards, Dave Ketchen, and Jeremy Short. Mastering Strategic Management: Evaluation and Execution.

(BCCampus Open Ed, 1st Canadian Ed.). https://opentextbc.ca/strategicmanagement/chapter/the-ceo-as-celebrity/

32Ibid.

33See Jim Collins, “The Misguided Mix-up of Celebrity and Leadership.” Conference Board Annual Report, Annual

Feature Essay (2001). https://www.jimcollins.com/article_topics/articles/the-misguided-mixup.html.

34Ibid.

35Ibid.

36See 1 Samuel 18:7.

37Griffith, “What Red Flags.” There are several accounts of Holmes dismissing questions from employees and

experts regarding the technology’s accuracy. A former director at Schering Plough responsible for evaluating

Theranos’ technology described Holmes’ answers to technical questions as “cagey and indirect.” Likewise, a

director at Pfizer described answers to technical questions as “oblique, deflective or evasive.”

38Michael Blanding, “Fake It Till You Fail: Elizabeth Holmes and the Theranos Story.” UVA Darden Ideas to Action

February 26, 2025. https://ideas.darden.virginia.edu/theranos-dardencase#:~:

text=Holmes%20was%20just%2019%20when%20she%20founded,others%20who%20had%20the%20exp

erience%20she%20lacked.%E2%80%9D.

39See Jim Collins, How the Mighty Fall (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009).

40See Cora Barnhart, “Organizational Failures and The Promised Land Experience,” Christian Business Review 13,

no. 1 (2024). https://hc.edu/center-for-christianity-in-business/2024/10/24/organizational-failures-and-thepromised-

land-experience/.

41Barnhart, “Organizational Failures and The Promised Land Experience.”

42Keller, Counterfeit Gods.

43See pages 393 and 394 in Dusya Vera and Antonio Rodriguez Lopez, “Strategic Virtue: Humility as a Source of Competitive Advantage,” Organizational Dynamics 33, no. 4 (2004): 393-408

44Keller, Counterfeit Gods.

45Jezior, “Lessons from the Theranos Toxic Culture.”

46Ibid.

47Another helpful observation from an anonymous referee. See Ernest P. Liang, “Resilience,” Christian Business

Review 1, no. 1 (2012). The article discusses how psychological safety, social capital (which emphasizes trust,

honesty, and self-respect), and accountability are among the Christian virtues that can provide an underlying

foundation in forming organizational resilience. https://hc.edu/center-for-christianity-inbusiness/

2023/06/26/resilience/.

48See Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow. (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011).

49Vera and Lopez, “Strategic Virtue.”

50“Narcissist CEOs are more likely to hire narcissists to top roles,” Neuropsych — May 14, 2024.

https://bigthink.com/neuropsych/narcissist-ceos-more-likely-to-hirenarcissists/#:~:

text=An%20estimated%2018%%20of%20chief%20executive%20officers,of%20empathy%2C%20a

nd%20a%20need%20for%20admiration.

51Vera and Lopez, “Strategic Virtue.”

52For more about addressing biases in decision-making, see Garrett Lane Cohee and Cora M. Barnhart, “Often

Wrong, Never in Doubt: Mitigating Leadership Overconfidence in Decision-making, Organizational Dynamics 53,

no. 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2023.101011.

53Ibid.

54Keller, Counterfeit Gods.

55Cohee and Barnhart, “Often Wrong, Never in Doubt.”

56Ibid. A pre-mortem assignment requires the decision-makers to pretend that a decision under consideration is

enacted, imagine the consequences one year in the future when it fails, and summarize the failure.

57Robert Lucas, “Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique,” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public

Policy 1, no. 1 (1976): 19-46. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:crcspp:v:1:y:1976:i::p:19-46.

58Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass Sunstein, Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (Boston: Little Brown

and Company, 2021).

59To learn more about improving long-term decisions, see Katherine Milkman, Todd Rogers, and Max Bazerman.

“Harnessing Our Inner Angels and Demons: What We Have Learned about Want/Should Conflict and How That

Knowledge Can Help Us Reduce Short-Sighted Decision Making,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 3, no. 1

(2008): 324–338.

60For more regarding how commitment devices impact savings, see Nava Ashraf, Dean Karlan, and Wesley Yin,

“Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a Commitment Savings Product in the Philippines,” The Quarterly

Journal of Economics 121, no. 2 (2006): 635-672. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25098802. See also Richard Thaler

and Shlomo Benartzi, “Save More Tomorrow™: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving,”

Journal of Political Economy 112, no. S1, Papers in Honor of Sherwin Rosen: A Supplement to Volume 112

(2004): S164-S187. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/380085.

61Richard Lints, Identity and Idolatry: The Image of God and Its Inversion (New Studies in Biblical Theology 36;

Apollos/IVP: Downer’s Grove, Illinois; 2015): 22.