[By William A. Morehead & Robert L. Perkins, 2015]

Abstract

The responsibility of a steward is to protect, use wisely, and be accountable for another’s resources. This article discusses the concept of biblical stewardship and research that examined the effectiveness of the systems of internal control in American based non-governmental (NGO) and non-profit (NPO) organizations with field operations in developing countries. The concepts, principles, and theories of stewardship, internal control, and accountability were explored. The data indicate weaknesses exist in the systems of internal control in these NGOs and NPOs. Relevant best practices are proposed to address these weaknesses and to give practical guidance on how to respond as both individual and corporate stewards of God’s resources.

Introduction

Donors to non-profit organizations championing worthy causes expect their gifts to be used for the cause. Yet, how many donors really know whether these organizations have sound systems of internal control to ensure monies are used wisely and in accordance with the donors’ giving instructions? Why should donors even be concerned about these organizations’ internal control systems, and what does this have to do with stewardship? Internal control is defined by the accounting profession as a process designed to provide organizations with reasonable assurance they accomplish their objectives of financial reporting, efficient and effective operations, and compliance with laws and regulations.1 Stewardship is similarly defined as the responsible use of resources, money, time, and talents, in the administration, management and control of an organization.2 Stewardship responsibility applies to both the individual giver and the corporate receiver. As individual stewards we are required to be productive with our time, talents, and resources. As corporate or organizational stewards, we have been entrusted with and are responsible for the resources of others. In the spirit of stewardship and consistent with sound internal control as defined by the accounting profession above, we should safeguard donors’ resources and ensure the optimal allocation, use and accountability of those resources.

Stewardship and Internal Control – A Biblical Viewpoint

A good steward does not give and forget but maintains an interest in and monitors the organization to which he has given. He does so to ensure gifted resources are used in a manner consistent with the donor’s intent and the organization’s mission and policies and procedures. A careful study of Scripture shows over half of Jesus’ parables have to do with the stewardship of time, talents, and resources .3 When Jesus speaks to nonbelievers, his message is about repenting of sins, letting him save you, and following him. However, when he speaks to believers he tells us how to have the abundant life, how to be the light and salt of the earth. Jesus also tells us how to be good stewards and managers of the material things in life.

A good steward does not give and forget but maintains an interest in and monitors the organization to which he has given.

Genesis 1 tells us God is the owner of all of creation and all of its resources. God places man in the Garden of Eden as a steward over His creation. Later in the Gospels, Jesus instructs us through the Parable of the Talents in Matthew 25:14-30 to manage our talents in such a manner that those gifts are multiplied and not squandered. Jesus reminds us of our responsibility as stewards again in Luke 12:48 where he says, “…when someone has been given much, much will be required in return; and when someone has been entrusted with much, even more will be required.”4 As believers and stewards, we cannot pretend to be innocent. In order to protect us from ourselves and to be good stewards, we must actively monitor the distribution of the gifts we have given or received from others and ensure proper internal controls and accountability are in place.

Methodology and Hypothesis

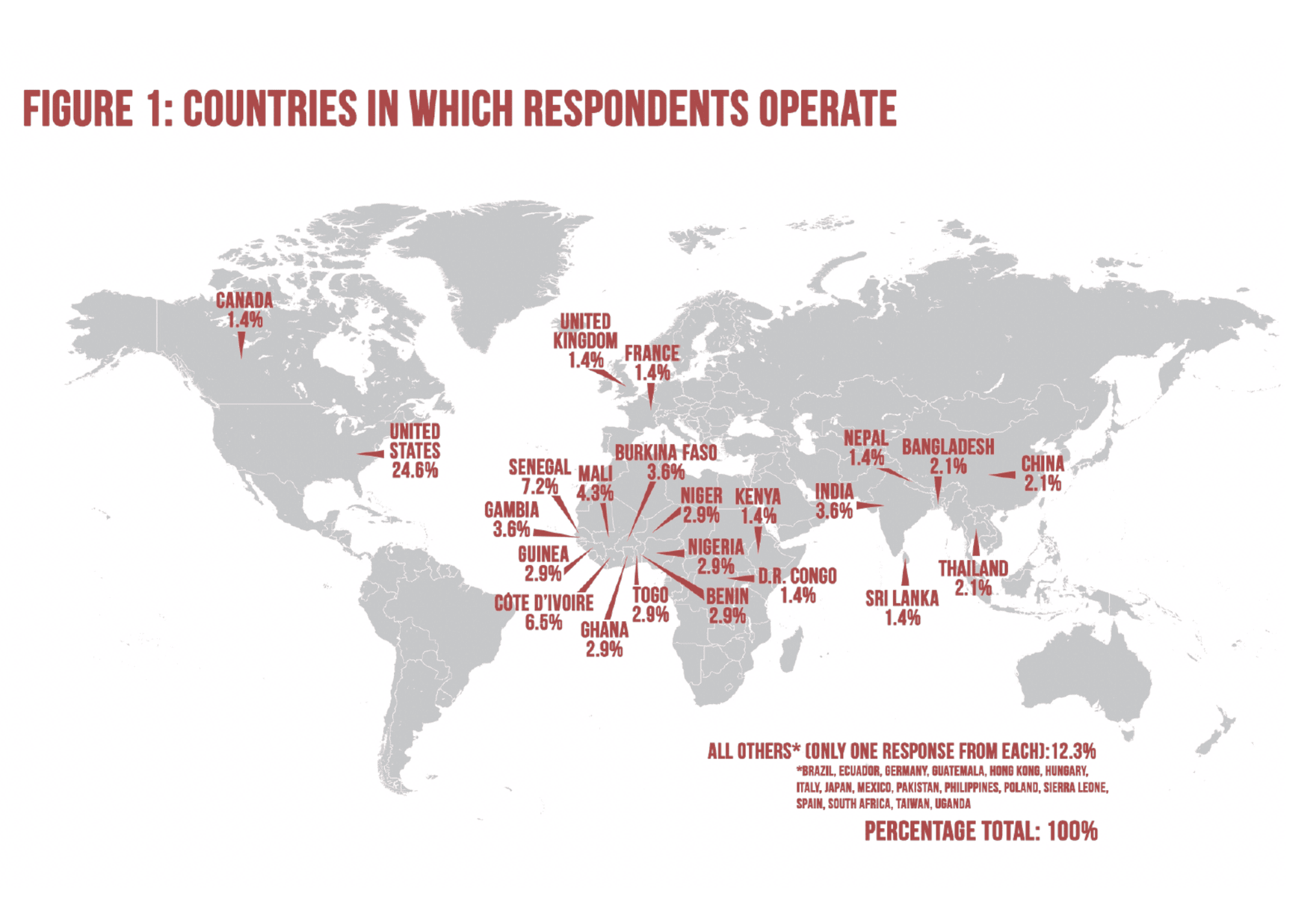

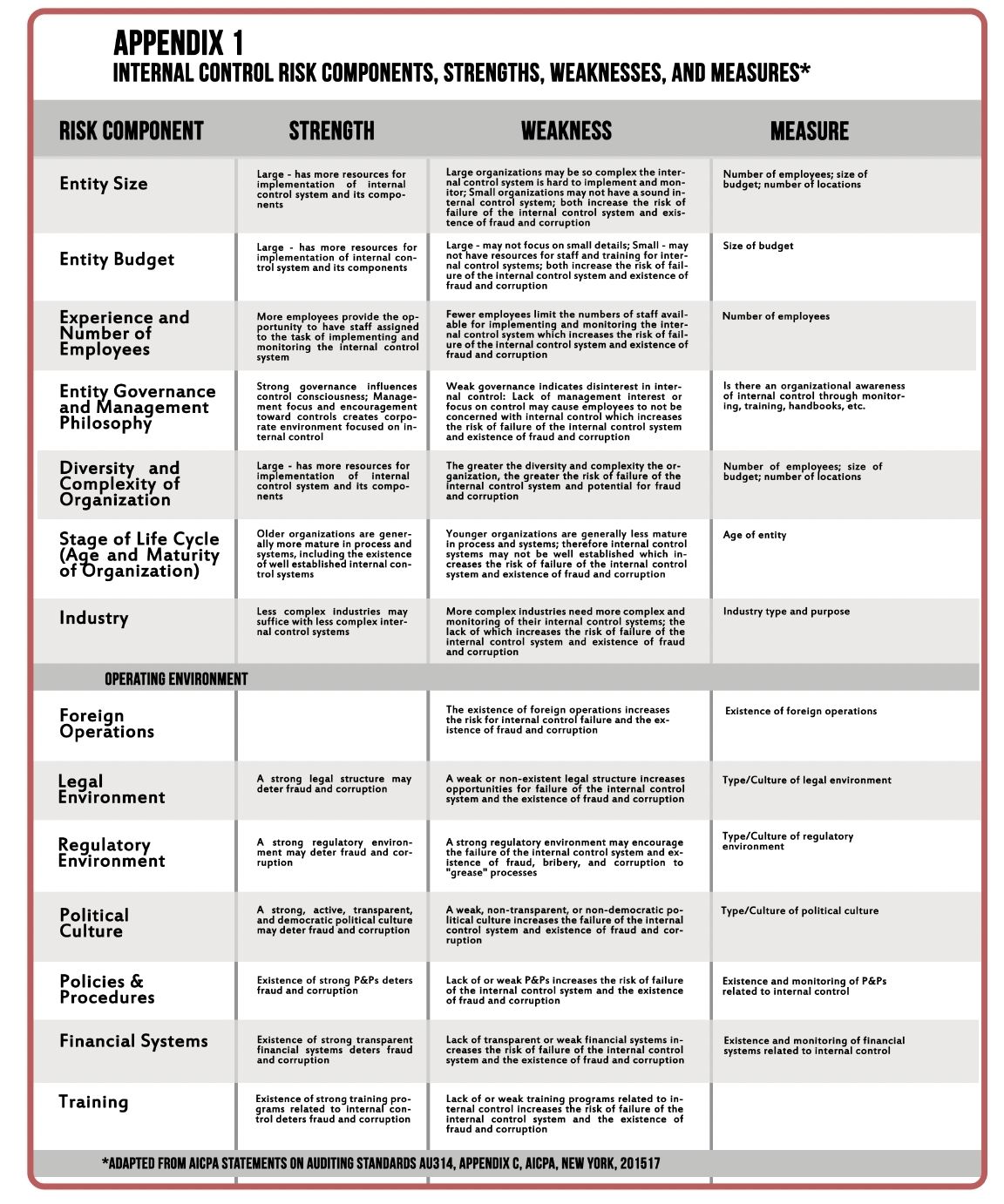

Christians give to many non-profit organizations including local churches, charities, and organizations with operations overseas. Our research specifically explored American-based non-governmental (NGO) and non-profit (NPO) organizations (hereafter, NPOs) with field operations in developing countries (see Figure 1). Nevertheless, most of our findings and recommendations easily apply to organizations here at home as well as those overseas. We examined the internal control systems of NPOs to determine their effectiveness and their ability to adapt to the various control risk components identified by the accounting profession which threaten an organization’s success (see Appendix 1). Our research also examined whether the corporate stewardship of accountability was followed by these NPOs, especially from the standpoint of internal control adequacies.

Our hypothesis is this: The internal control systems of these NPOs are not adequately designed, implemented, and monitored and therefore corporate stewardship for donors are not adequately practiced.

A sound internal control system is the primary accountability and governance tool an organization can establish and use for achieving reliability of financial reporting, operating efficiency and effectiveness; the compliance with laws, regulations, and organizational policies; and to provide accountability and stewardship for stakeholders.5 No two entities will, or should, have the same internal control system. Organizations and their systems of internal control diff er dramatically based on their industry, size, purpose, management philosophy, diversity and complexity of its operations, local culture and operating environment, and legal and regulatory requirements.6 For Christian organizations, biblical ethics and values should be a part of any good internal control system. In fact, it should drive the entire design of the system. While no system is foolproof, the absence of sufficient internal control creates an opportunity for abuse, fraud, and corruption. It sends a message to employees, stakeholders, and individuals outside of the organization that management does not care about protecting the entity’s assets.7

The concept of stewardship accounting has its foundation in the early stages of accounting centuries ago and contributes to the understanding of accountability and internal control. Stewardship accounting was founded on the separation between capital ownership and management and centered on the notions of responsibility, accountability and control.8 The concept of a steward making financial exchanges for someone else creates accountability among two or more parties who rely upon reciprocity and trust. When shared with the public, this trust creates a stronger sense of accountability and an awareness the steward was a secure keeper of their funds and accountable for his or her actions. Today, organizations fulfill the concept of stewardship accounting and internal control by providing similar accountability function to its stakeholders.9

Internal Control and Stewardship in NPOs

Financial reporting requirements for nonprofits are quite different from for-profit entities. By comparison, things are fairly simple in the for-profit world. The goal of a for-profit business is to make money for its owners; and, most owners are content as long as their dividend checks are deposited in a timely manner without knowing any other specific organizational details. In the nonprofit world, however, donors want to know what is going on with NPOs. As good stewards, NPOs are required to maintain accountability and credibility with the donor base demonstrating they have operated the programs efficiently, effectively, and consistently to honor the use of the funds and accomplish their mission and goals.

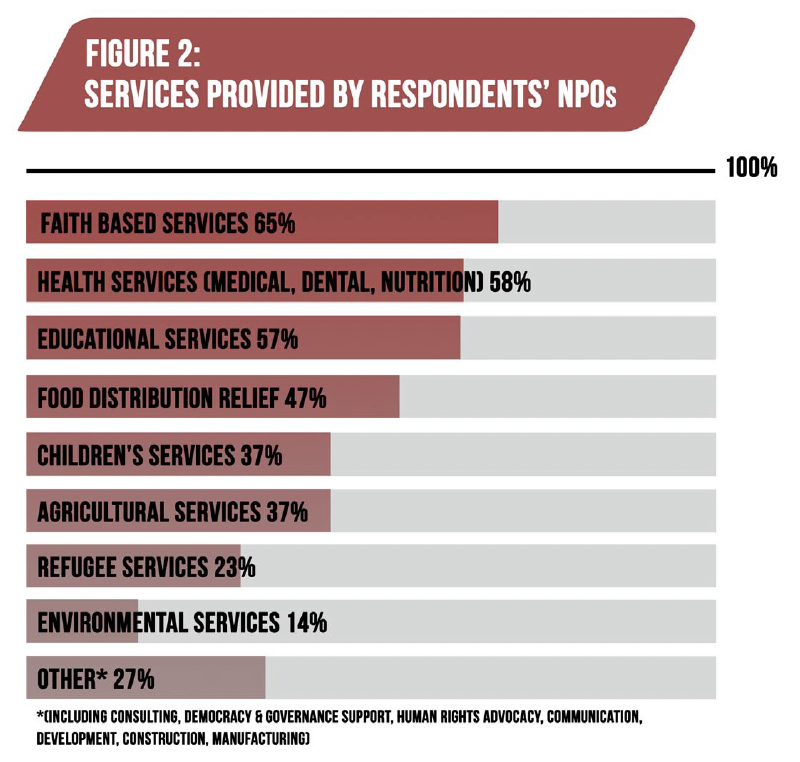

The missions of the non-profits are inherently service-driven (for example: NPOs may provide faith-based, educational, disaster relief, medical services, and food distribution services – see Figure 2). Because their missions are not profit driven, NPOs must focus on performance driven goals and answer the question: are their services provided with efficiency, effectiveness, and in compliance with donor wishes and organizational policies and procedures? As the NPOs are performance driven and service delivery focused rather than profit focused, they are often more vulnerable to breaches in their internal control.10

For example, the missionary is focused on evangelism and the healthcare worker is focused on saving lives; yet, neither is focused on internal control although it is necessary to keep both in the field. One NPO administrator emphasized what is at stake: “When trust gets shaken, it reflects in the bottom line of charitable organizations. The average small donor bases a lot on trust. When that’s eroded, it reflects on the organization and the nonprofit community as a whole.”11

Just in this millennium in the United States, donors have seen many examples of fraud and corruption scandals where assets were misappropriated and donated funds were misdirected into other projects or toward personal gain by one or more of the organization’s leaders in both profit (e.g., WorldCom, Tyco, Enron) and non-profit organizations (e.g., United Way, Red Cross, International Mission Board). These scandals have raised the general public’s awareness of and demand for stewardship and accountability from all types of organizations, especially NPOs. The vigilant efforts of NPOs to demonstrate accountability is critical to their ongoing financial viability and is necessary to keep donors interested in the continued investment of their time, talents and resources.

Empirical Findings

Our research sought answers to 55 questions (See Appendix 2) developed to determine whether the NPOs’ internal control systems were vulnerable to the various risk components identified in the professional auditing standards. From the survey data, we discovered the NPOs experienced challenges and weaknesses in their present internal control systems, supporting our hypothesis.

Finding One: Foreign Operations

The very existence of foreign operations does not mean the internal control system will fail. However, due to unstable and developing economies and political environments, it often signals to management there is need to compensate for this weakness by strengthening controls over other risk components.12 The data show respondents lived and worked in countries they perceived to be corrupt, were politically and economically unstable, and where some within the NPOs even admitted to paying bribes in order to obtain government services. These situations indicate a greater risk for an unsuccessful internal control system. NPOs operating in foreign environments must be prepared for cultural and political differences and must ensure their systems of internal control make appropriate accommodations for the countries in which they operate.

Finding Two: Organization Diversity, Size, Complexity and Type.

The data from the research show the NPOs operate a variety of diverse and complex services (faith-based, medical, educational, environmental, and agricultural, etc.) requiring the skills of very specialized or technical staff (evangelists, doctors, teachers, engineers, and farmers, etc.).13 Further, these NPOs had few employees and limited budgets at their field offices. The staff and resources also were generally focused on the field services, not internal controls. NPOs should ensure their internal control systems to be modified to accommodate the diversity, size, complexity and type of organization. Staff assignments should also include establishing, maintaining, and monitoring elements of internal controls.

Finding Three: Operating Environment.

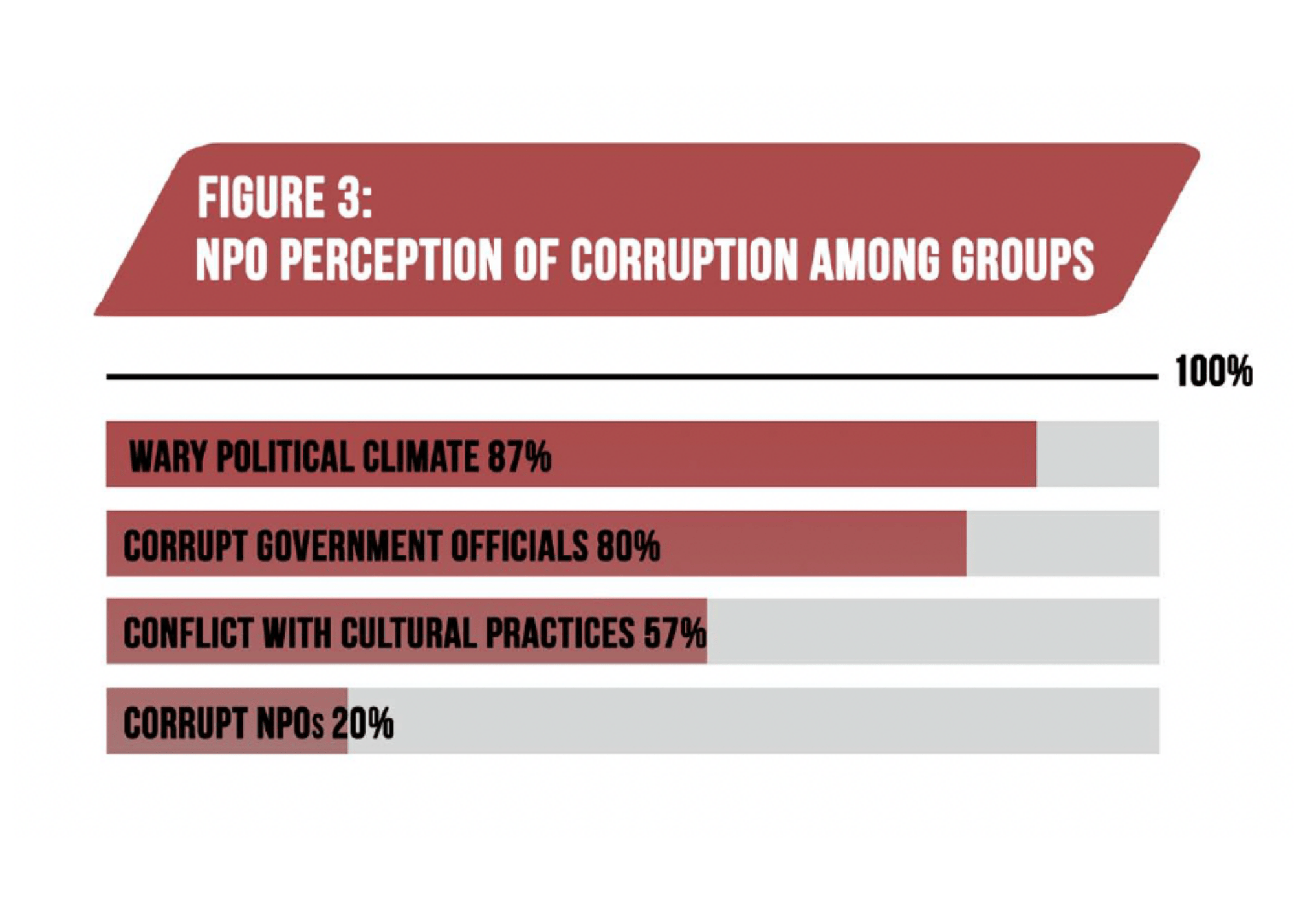

The operating environment (including the local culture, legal and political climate) contributes to the success or failure of the internal control system.14 The more stable the operating environment, generally the more successful the internal control system. Survey respondents working in NPO field offices were asked several questions to gauge their perception of corrupt behavior among business people, political leaders, clergy, and other groups of individuals in the field country where they work. The data show a high level of perception of corruption among government officials and other local NPOs. Staff were wary of the political culture in the countries in which they operated, and their organizational values were often in conflict with local cultural practices (see Figure 3). This shows NPOs must pay special attention to their operating environments and incorporate specific elements (such as maintaining extra security, using redundant financial checks and balances, and transferring funds to the field only as needed, etc.) within their systems of internal control to address such vulnerabilities.

Finding Four: Organizational Policies and Procedures.

Organizational policies and procedures, codes of ethics and sound financial systems exist to encourage transparency, accountability, stewardship, and successful internal control. They need to be reviewed and updated at least annually.15 Survey respondents indicated their organizations generally had good policies, procedures, codes of ethics, and financial systems. Yet, only 20% indicated these had been reviewed or updated within the 24-months period prior to the survey. This signals a weakness in control per professional auditing standards and should be addressed.

Finding Five: Training over Internal Controls.

Two-thirds of the respondents indicated they had received training on internal controls.16 Yet, only 36 percent of the respondents indicated their training was culturally adapted to address specific issues found in their local field offices. NPOs must regularly provide employees with training regarding updates of policies and procedures. The training should also cover organizationally specific risk components they face due to its operation, location, complexity, etc.

NPO Best Practices

No internal control system will completely ensure organizational success in achieving the objectives of integrity of financial reporting, efficient and effective operations, and compliance with applicable laws and regulations. A sound control system exhibits management’s best effort to lead their organization in the right direction while providing stewardship and accountability over organizational resources.

The study shows most NPOs attempted to exercise good stewardship and provide transparency and accountability to their stakeholders. Yet our findings indicate these NPOs faced numerous challenges with various risk components in internal control. Some of these risks were internal, such as updating policies and procedures and providing adequate training, while others were external, such as the cultural, legal and political environments. Despite the challenges, management should design its own system of internal control addressing each risk component (per Appendix 1), paying careful attention to those specific risks the organization may be most vulnerable to (see ICS Design Considerations).

Although our research focused on NPOs operating in developing countries, the lessons and concepts of good stewardship and internal control apply to NPOs operating anywhere. As stewards of God’s resources, we have the responsibility to use resources wisely. At the same time, we must be watchful of the organizations we support financially to ensure they fulfill their stated objectives.

Leaders with corporate (recipient) stewardship responsibilities must make sure the organization’s mission is properly fulfilled as they are fully accountable to their financial supporters. They must design the accountability systems with sound principles of internal control, carefully addressing the various risk components (including the diverse operations, size, location, purpose, and operating environment) where the organization is most vulnerable.

May all givers be as in Exodus 36:2-7, where, as productive individual and corporate stewards, they give out of their abundance to the point where there is no more need. Giving occurs like this when we view giving as the Apostle Paul did, as something we want to do rather than something we have to do. Furthermore, may corporate stewards ensure the talents, gifts, and resources of their donors are used in the most efficient, effective, and mission focused manner and accounted for with the highest level of integrity. Only then will all deserve the accolade from the Owner, “Well done, my good and faithful servants” (Matthew 25:21).

ICS Design Considerations

An Internal Control System (ICS) is an intangible structure unique to each entity and designed to help the entity achieve efficient and effective operations, financial reporting, and compliance with laws, regulations, and entity policies. As such, the implementation of the ICS and the evaluation of the individual risk components should vary from organization to organization. Consider Entity Size. Possible tangible measures include number of employees, size of the budget, and number of locations of operation. When examined with the various strengths and weaknesses, the following may be considered:

- If an entity has a small number of employees assigned to several locations each with limited operating budgets, it should consider various separation of duties among the limited number of employees to ensure no single employee has complete responsibility for all financial duties. For example, one person may have all the responsibilities of paperwork generation and data entry of the financial operation, but a separate person can simply provide the final signature or electronic approval to authorize the transaction. This one element ensures at least two people review all transactions and will provide a separation of duties (a check and balance) over the financial operations.

- Multiple locations create more challenges in an ICS. Yet with increased technology, financial operations can be centralized to a corporate location where enhanced internal control procedures are in place. This would minimize risks of financial reporting failures or unauthorized transactions.

- Larger budgets may provide greater resources for enhanced ICS such as better financial systems, enhanced technology, more resources (i.e.: better skilled staff , more staff , staff with a focus on internal control, training for staff , etc.). Smaller budgets will likely impact an entity adversely.

Designing Internal Control Systems based on biblical values and ethics

For faith-based entities, the priority for the ICS should be the entity’s vision and mission to determine whether specific organizational goals and objectives are being achieved. The organization’s purposes must be biblically grounded and ethically driven. The organization’s board of directors and administrators should make operational decisions which are God honoring. From a practical standpoint, management may find it wise to consult with a financial accounting professional or industry specific guidance to establish the most effective ICS. Soliciting accounting professionals with a Christian focus through the “word of mouth” method may be the best route. Once a professional is hired, make sure the scope of work is clearly documented in writing through a letter of engagement. NPO management must accept the responsibility of establishing the ICS as a “hands on task” as management is clearly responsible for the ICS. Once established, the ICS must be monitored and periodically evaluated, at least annually, to ensure entity objectives are being achieved.

Appendix 2 Partial Listing of Questions Asked in survey

- Are you currently (or formerly) an employee of an American-based non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-profit organization (NPO) that has headquarters in the U.S. and field offices outside the U.S.?

- My organization provides field staff with training regarding business internal controls?

- This training in internal controls is adapted to fit local cultural interpretations of corruption? Please rate your agreement with this question using a scale of 1-5 where (5) means “Strongly Agree” and (1) means “Strongly Disagree.”

- My organization provides field staff with training regarding fraud and corruption prevention and detection techniques?

- In your field country, have you been required to give a bribe, gift, or favor to obtain a service or product you or your organization were entitled to?

- How many times have you been required to give a bribe, gift, or favor for services?

- What is your perception of corruption in the country where you are working? Please rate your agreement with this question using a scale of 1-5 where (5) means “Very High” and (1) means “Very Low.”

- Has your organization been a victim of fraud or corruption at your field office within the past 0 to 12 months, 13-24 months, 25-36 months, No, or Don’t Know?

- Do you think your NGO operates in a country (countries) or region (regions) that subjects your NGO to more corruption?

- Does your organization have staff whose primary assignments are focused specifically on fraud and corruption prevention and detection?

- How often does your organization review and update its internal control systems?

- How many years of experience do you have in the provision of field services with your present organization? In your career?

- In which country do you presently live?

- In which country (countries) does your field office provide service coverage?

Note: An electronic survey was used with 55 questions. The survey was distributed to 233 individuals and organizations around the world operating as or within American-based NPOs in developing countries. 158 individuals visited the survey; only 64 surveys were considered complete and valid for the research. Because the survey was anonymous, we were not able to determine which individuals or organizations responded. While this research began with the intention of conducing a descriptive statistical analysis, it is much more of an inferential analysis due to the limited data received from the surveys.

Notes

1 Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) of the Treadway Commission, Internal Control – Integrated Framework Update (2013). AICPA New York. www.coso.org.

2 The Oxford English Dictionary, Volume XVI (1989). Oxford University Press. Oxford.

3 Frank Pollard, “The Sermon on the Amount” (sermon preached for The Baptist Hour, December 9, 1993).

4 Luke 12:48

5 Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. 2014 Report To The Nation on Occupational Fraud and Abuse (2014). Austin, TX: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners; Ibid, COSO

6 Ibid, COSO

7 Ibid, and ACFE and American Society of Association Executives, “Self-Regulating the Nonprofit Sector,” Association Management, 56 (4) (2004): 24. Washington, D. C.: American Society of Association Executives. Database: Business Source Elite.

8 Lemarchand, Y. “Double Entry Versus Charge and Discharge Accounting in Eighteenth-Century France,” Accounting, Business & Finance History, 4 (1), (1994): 119-145. 9 Dickhaut, J., & McCabe, K. “The Behavioral Foundations of Stewardship Accounting and a Proposed Program of Research: What is Accountability?” Behavioral Research in Accounting,

9 (1997): 60-87.

10 Zack, G. Nonprofit Fraud: When the Bottom Line is Not the Bottom Line (2003). Austin, TX: Association of Certified Fraud Examiners. Accessed November 2, 2004. http://www.cfenet.com/resources/articles/ print.asp?articleid=228

11 Ibid, ACFE

12 Ibid, COSO

13 Ibid, COSO

14 Ibid, COSO

15 Ibid, COSO

16 Ibid, COSO

17 American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Professional Auditing Standards (2015). AICPA, New York.

About the Author

William Morehead is an Associate Professor of Accountancy at Mississippi College. Prior to joining Mississippi College in 2011, Morehead served 27 years in various roles of government financial management for the State of Mississippi including Vice President of Finance and Administration for Delta State University, Chief Financial Officer at Mississippi State Hospital, and as an auditor for the State Auditor’s Office. Morehead and his wife, Audrey, also served as missionaries in West Africa with the International Mission Board. Morehead holds a Ph.D. in International Development from the University of Southern Mississippi, a Master of Accountancy from Millsaps College, and a Bachelor of Business Administration from Delta State University.

Robert Perkins is an Assistant Professor of Law and Ethics at Mississippi College. Prior to joining Mississippi College, Perkins served as a Special Assistant Attorney General and Director of Licensing for the Mississippi Department of Insurance. Perkins holds a Doctor of Jurisprudence from Mississippi College and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Mississippi.