[By Hallqvist Albertson, 2016]

Abstract

A survey of a small group of Christian CEOs was employed to examine the meaning and implications of the First Commandment in the modern marketplace. The study illustrates the difficulties for business leaders to integrate faith in everyday business practices. The paper offers some practical insights for Christian business leaders who desire to integrate their faith at work but must battle competing interests, even “idolatries” in the secular business environment.

Introduction

George, an older man, was a successful Christian businessman who wanted to mentor people in life, business, and the Christian faith. He was self-made, amassing a net worth of hundreds of millions of dollars. He lived modestly in a home that he had purchased forty years earlier; drove stock Fords for a decade before trading them in; gave generously of his time to all who asked and to some who did not, and spent most of his wealth during his lifetime helping his church and other Kingdom-enriching causes. In most respects, George was a modern-day exemplar of how the Christian businessperson should live. One thing curious about George, however, was that he would often proclaim: “Don’t do business with Christians. They are idolaters!”

Over the last several decades as I have studied faith and business as both a practitioner and an academic, George’s admonitions have grown faint in my thoughts, being replaced by more practical ideas of faith-work integration in the marketplace — that is, until recently, when I read Kyle Idleman’s Gods at War.1 Idleman’s thesis is that idolatry is very much alive today in the post-modern era. While humans, at least in the modern day West, rarely make statues or other images and bow down to them, we do elevate people, ideas, and objects to the place of God in our lives. This paper is an attempt to probe further the meaning and implications of “idolaters,” as brought forth by Idleman and George, in the context of the First Commandment and the twenty-first century marketplace.

Biblical View of Work

The earliest biblical reference to work appears in Genesis 1:1, in which God began the work of creating the heavens and the earth. This reference concludes in Genesis 2:2 with completion of that work on the seventh day, when God rested.

The biblical narrative continues the concept of work by stating that Adam had a vocation before the Fall: he was a worker in and keeper of the Garden of Eden (Gen 2:15). Adam’s task is described by the Hebrew word Avodah, used elsewhere in the Old Testament over one hundred times to mean “work and worship.”2 Therefore, from the beginning of biblical history, human vocational endeavors correlate with worshiping God.

Various vocations are recorded in the New Testament as well. Mark 6:3 reports that Jesus’s vocation was that of a carpenter. Joseph, and possibly also Mary, worked as a tradesperson (Matt 13:55). Matthew 4:18 calls Andrew and Peter fishermen. Acts 9 tells that Dorcas made clothing, while Lydia was a trader in purple cloth (Acts 16:14). Acts 18:3 indicates that Paul was a tentmaker. The biblical text stresses the importance of working well, as if the worker were working for God (Col 3:23-24; Eph 6:7).

God uses work as part of his plan to spread the gospel message throughout history. Although Christianity spread initially through dedicated evangelists and missionaries, it also spread organically through trade and commerce, as people working in business vocations encountered their non-Christian business partners and shared the faith in that process.3 Prophetically, Isaiah 65:22-23a tells us that in the New Jerusalem we will worship God through our work and enjoy the fruit of our labor.

Work is also used biblically to give cautionary tales against idolatry. For example, in Luke 12:13-21, Jesus tells the story of what has often been called “The Rich Fool.” It could equally as accurately be called “The Doom of the Materialist.” In the text, Jesus warns about the dangers of a life lived without God – a life that worships self, work, and personal comfort. The parable’s foolish main character lived a life as if God did not exist. When he perished, he left all his worldly accomplishments behind. Work had become his idol.4

In accordance with this theme, Colossians 3:5 calls greed idolatry. Greed causes us to trust in things rather than in the God who gave us those things. The Epistle to the Romans was written to a Christian audience and the Acts of the Apostles was written to non-Christians. Wright asserts that Romans portrays idolatry as rebellion against God and spawning wickedness, while Acts portrays idolatry simply as ignorance and valueless.5 This certainly implies that God will judge believers more harshly than non-believers on the issue of idolatry.

Consequently, it appears that from a biblical perspective, there is a link between work and serving God. Veith argues that Ephesians 2:10 expresses how the Christian worker is “God’s workman” and is to do “good works” in order to serve others, as commanded by Matthew 20:28.6 Sherman and Hendricks argue that God created work for five reasons, i.e., (1) serve humanity; (2) provide for humanity’s own material needs; (3) provide for the family’s needs; (4) create wealth to give to others; and (5) love God.7

Faith at Work: A Historical Survey

Sometime between the early New Testament period and the Reformation, the idea of vocation as secular work became subjugated to a calling in the Church in terms of honor and holiness.8 With the advent of the Reformation and the notion of the priesthood of all believers, both Martin Luther and John Calvin advocated for more intensive Scriptural education and training for persons in secular vocations, as well the adoption of theology in which secular work was once again viewed as equally important as clerical work.9 By the end of the nineteenth century, the minister Charles M. Sheldon introduced the idea of, “What would Jesus do?” and suggested that this question should be considered in the context of the political, social, and cultural changes occurring in America at the time, including in the workplace.10

In the early twentieth century, when Christianity was still the dominant religion in North America, it was considered inappropriate to pray or discuss faith at work.11 This was often called the “Sunday-Monday gap.”12 Yet many companies, particularly assembly line manufacturers on the East Coast, scheduled work hours for their employees so that they could attend a weekday Mass or special religious services without missing work.13

Beginning in the 1960s and continued into the nineties, a number of factors brought about the breakdown of the separation between faith and work.14 In this time period, literally hundreds of books were published that dealt with a biblical view of work.15

In the last fifteen years, there have been a plethora of books published on the subject of biblical work, faith and work, tent-making, and business as mission (BAM).16 The literature tends to be predictably formulaic, usually divided into four parts. The first part begins with an argument that business is an actual calling from God as much as, if not more than, a paid fulltime Christian ministry position.17 The second part is commonly a manifesto for collapsing the sacred and secular and living as Christians every day at work and not just on Sundays, truly applying beliefs in the marketplace.18 The third part usually includes a how-to guide for integrating faith and business, based on the author’s personal experiences in the marketplace.19 The texts often finish with glowing stories of individuals and companies who applied biblical principles to the marketplace, how they prospered and changed the world for Christ.20

It is important to note that the idea of “integration of faith at work” potentially means different things to different people at different times and in different places. To some, integration of faith at work might mean praying before a meal. To others, it might mean personal evangelization in the workplace. To still others, it might mean pursuing Christ-like conduct in business transactions.21 For this paper what is important is whether the study participants tried to integrate their faith at work in some fashion, and not what that specifically meant to them.

We examine the following hypothesis in this essay: there would be a recognizable level of integration between a Christian business leader’s faith and praxis, and those who consciously attempt to integrate faith at work would demonstrate consistently proactive effort and success. In this study, a small survey was conducted to shed light on this hypothesis.

The Empirical Study

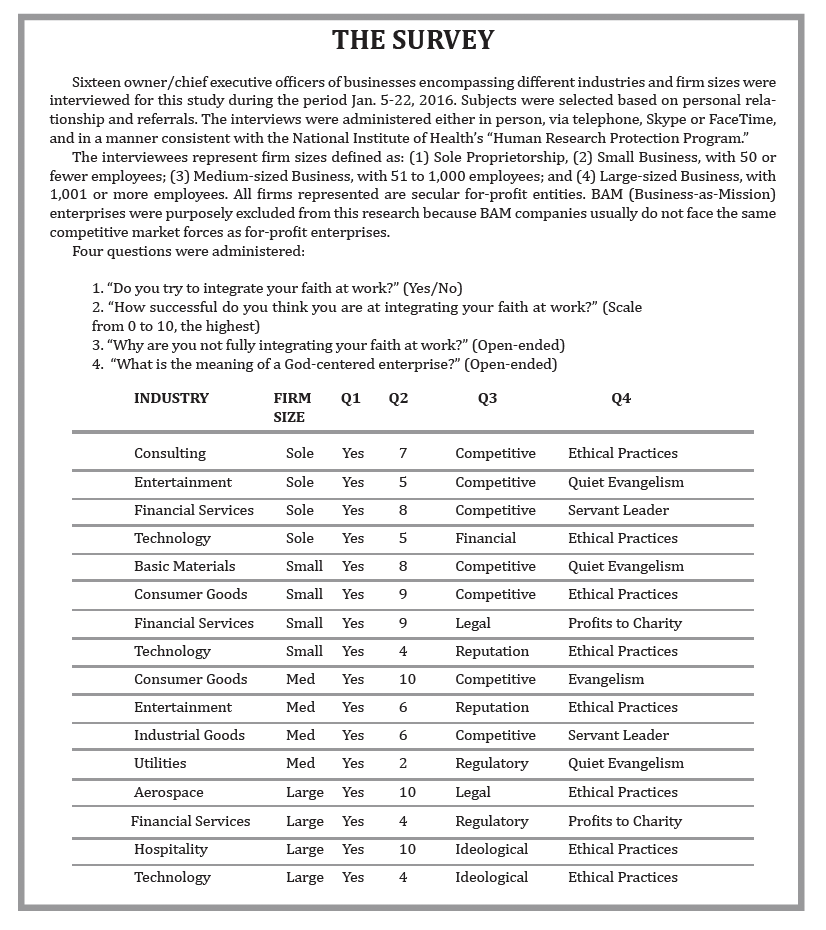

The study looked at the experiences of sixteen business leaders and CEOs.22 Four questions were administered in personal interviews.

- “Do you try to integrate your faith at work?” – answer yes/no

- “How successful do you think you are at integrating your faith at work?” – answer on a scale of zero to ten, with zero being the lowest and ten being the highest.

- “Why are you not fully integrating your faith at work?” – answer open-ended

- “What is the meaning of a God-centered enterprise?” – answer open-ended

A summary of the answers is provided in the box The Survey.

Observations

The response to the first question, in which all the respondents indicated that they do try to integrate their faith at work, is expected. Since these business leaders were all self-professed Christians and volunteered their time to help with this research, it would follow that they are conscious in their effort in integrating their faith at work, albeit to varying degrees of success.

It was a bit of a surprise to find that, in response to the second question, more respondents did not report a higher degree of success at the integration effort. It has been the author’s experience that people tend to overestimate their achievements in matters of faith, so the fact that only half of the interviewees rated their success as at least 7 out of 10 (a “C” or better) is disappointing. There could be a variety of explanations for this result. For example, because the respondents were leaders who regularly make difficult judgments on performance, they might be hyper-self-critical. Another possible (if ironic) explanation may be related to their personal faith. These individuals may presumably see themselves, as the Bible asserts: “humans as sinners.” This perspective echoes Paul when he wrote “What a wretched man I am!” (Rom 7:24 NIV). In light of the answers from the following open ended questions, the first explanation is perhaps more likely (see discussion below)

Questions three and four were the most interesting with regards to the intent of this research: exploring the meaning and implications of the First Commandment in the context of the twenty-first century marketplace. Seven of the sixteen (43%) interviewees reported that they are not currently fully integrating their faith at work because of “competitive” reasons, meaning they feel they would be at a competitive disadvantage by integrating their faith more fully. Another four (25%) reported that they do not integrate their faith and work because of legal and/or regulatory concerns. Two of the sixteen (13%) were ideologically opposed to integrating faith and work. They believe in the Sunday-Monday gap, in which the faith one practices on Sunday at church should not influence what they do in the office on Monday. Two more (13%) reported being afraid that integrating their faith and work would hurt their reputation and that they would be thought of as the “type of Christians one sees on television and the movies,” being mocked by mainstream culture, or as a “Bible-thumper.” Finally, a single individual (6%) reported that he did not integrate his faith at work because of “financial” reasons.

In summary, a majority (88%) of the survey participants failed to integrate their faith at work because of fear: fear concerning competitive advantage, personal reputation, legal and regulatory ramifications, and financial consequences.

Fear is a powerful motivator and can be God-given. For example, if a child has ever touched a hot stove with her hand and been burnt, she is unlikely to repeat this behavior because of healthy fear. Mature Christians who succumb to fear of personal loss in contrary to the biblical narrative can fall into idolatry, however.23 Mouw tells how, when he was President of Fuller Theological Seminary, had dispensed with pastoral and biblical niceties when terminating employees because he had to instead focus on the “legal considerations” of termination.24 His fear over legal consequences overshadows proper conduct in accordance with biblical principles. When a Christian business professional operates out of fear, he is worshipping fear, rather than God.

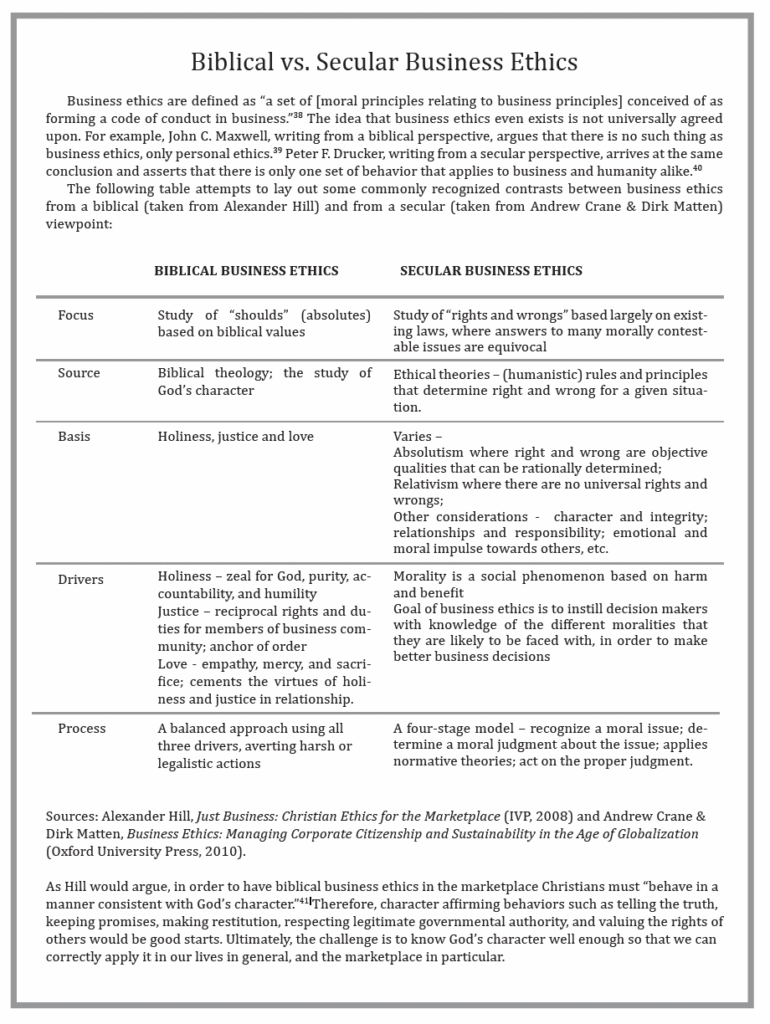

Ethical behavior is important in business, but secular ethics is not necessarily biblical. Half of the respondents felt that a God-centered enterprise implies behaviors that are ethical. However, ethics is often perceived to be relative, meaning different things to different people. To the survey participants, the meaning encompasses concerns for the environment and creation care, providing employees with living wages and benefits, having integrity in paying bills and taxes on time, advocating for LGBT and civil rights, and giving back to the community. Two participants consider it important to give a portion of profits to charity and another two indicate that a God centered enterprise means that they should be servant leaders, using their businesses to advance a higher cause generically defined as promoting human prosperity.

Three of the respondents also felt that a God-centered enterprise should involve “quiet evangelism,” which one of them defined as (mistakenly attributed to St. Francis of Assisi) “Preach the gospel, and if necessary, use words.” Another considers “evangelism” as the use of the company’s resources to preach the gospel and fund missionaries. The difficulty with the ethics-centric view for a God centered enterprise is that ethics, without the grounding of a biblical worldview, is merely a human-construct based on secular values (see box Biblical vs. Secular Business Ethics). Dedicated pursuits of secular ethics could indeed lead to idolatrous practices.

The survey responses are handicapped by the preliminary nature of this study. To provide a better understanding of the reasons behind many of the interview responses, additional research is required, such as interviews with the subjects’ employees and colleagues to determine if the interviewees’ valuation of their abilities align with others’ perceptions.

Idolatry in the Marketplace – Further Thoughts

This study brings forth some thoughts on how business professionals might attempt to reconcile God’s and their business priorities.

Resist the Idol of Fear

As human beings, we all have diff erent degrees of pride, envy, jealousy, and greed in our hearts. We desire success. We want to be liked. We are willing to tell a “white lie” if it seals the deal, makes things go smoother, or reduces workplace drama. The survey indicates most of us also worship an idol called fear; this is an idol bigger than the 420- foot Spring Temple Buddha in China that people physically bow to in worship.25 Christian businesspeople, including myself, often bow to and worship fear, rather than worshiping the God of the Bible and his admonition to trust him and not fear (Pslm 56:3-4; Matt 6:33; 2 Cor 3:4- 6; 1 Tim 6:17).

Mature Christians who succumb to fear of personal loss in contrary to the biblical narrative can fall into idolatry

Had the Ten Commandments begun just with moral teachings, designed to regulate human behavior toward one and another, such as do not lie, steal, or commit adultery, that text would not be significantly different than the moral teachings found in other religions, such as the Eightfold Path of Buddhism, the Smritis of Hinduism, and the Adj Granth of Sikhism. But these commandments begin with a prohibition of other gods before God. One could obey all the other nine commandments meticulously, yet still betray God’s covenant by having other gods at heart.26

The First Commandment, therefore, is just that: the primary commandment. It is not a suggestion, a good idea, or a mere philosophical construct. It is an absolute. We must repent from worshiping these other gods in the marketplace in order to exhibit obedience to the First Commandment. And we need to remember that repentance is more than just saying we are sorry for worshiping idols; repentance involves a change in current and future behavior.

Integration Follows Mission

Integration follows a clearly defined mission. Christian business professionals need to define their concept of Mature Christians who succumb to fear of personal loss in contrary to the biblical narrative can fall into idolatry. christian leaders on faith and work mission in order to clarify what God-centered enterprise actually means.

Charles Van Engen sees mission in terms of “sentness,” sending the people of God to intentionally cross barriers from church to non-church, faith to non-faith, to proclaim by word and deed the coming of the kingdom of God in Jesus Christ.27 We see this in Ephesians 4:11, in which Paul writes about unity in the body. The apostles had a different mission than the prophets. Christian business professionals have a different mission than each other, but that each does have a mission.

Neill asserts that “If everything is mission, then nothing is mission.”28 When Neill made this statement nearly fifty years ago, the problem he saw in the church was that mission was being defined so broadly that it was increasingly difficult to offer focus. How one perceives mission dictates how one engages in mission.

For example, historically, the church has spoken of God the Father sending the Son, and the Father and the Son sending the Holy Spirit.29 In 1934, Karl Hartenstein, a German missiologist, coined the term Missio Dei based on the work of Karl Barth and his perception of a diff erent movement: one of the Father, Son, and the Holy Spirit together sending the Church.30 Others see mission as just “followers of Jesus…seeking harmony by modeling their lives after his.”31 And then there are those who hold that Christian mission is “to know Christ and to make him known.”32

In business how Christian business professionals perceive mission will dictate their actions in the marketplace If, for example, mission means making Christ known to the nations, then the business leader will ensure that the business operations are set up for that purpose. This model would be different than that of a business whose mission was to make as much money as possible in order to donate a percentage of profits to charity, or if mission was considered to be synonymous with ecological creation care. And all of these approaches would likewise be different from mission as increasing shareholder value. It is not possible to begin the process of integrating faith at work until one knows what the mission is.

God’s Way Is Also Good

Business Christians need to break the conventional wisdom that the world’s ways of doing business are more “successful” or “better” than God’s ways. We tend to believe a lie that being Christian or applying biblical principles in the marketplace is somehow bad for business. Research has shown that ethical business conduct can be a source of competitive advantage because it reduces transaction costs of litigation through its trust-building activities and social capital preservation.33 As Christians in the marketplace, modeling biblical ethical behavior could be good for business.

A lady I know is a supplier to the entertainment industry. She applies biblical principles diligently in her personal and professional lives. While she is honest, trustworthy, reliable, competent, and in high demand, she declines lucrative contracts if the project mocks God, is violent, pornographic, or profane, or in some other way violates what she sees as redemptive activity. One would think that this woman would have difficulty surviving professionally in Hollywood. In fact, the opposite is true; she is so sought-after that she raised her rates several times last year because she had too much work!

This is the case as well, in examples like Arthur Guinness and his mission to create a highly successful beer business that benefits the kingdom.34 More recently, the Christian business leaders at Tyson Foods,35 Aflac,36 and Marriott37 enjoy successful careers while striving to follow the biblical narrative in the marketplace.

Christian business professionals need to define their concept of mission in order to clarify what God-centered enterprise actually means.

Let Our Faith Shine

We need to apply our faith more in our spheres of influence, whether as an entry-level intern or a seasoned CEO. We must actively trust God, his promises, and his word by putting away the idols, especially the idol of fear, and worshipping him alone in the marketplace. Business leaders need to make it easier for their employees, coworkers, bosses, friends, and family members to put away idols as well. By word and deeds, they should exhibit God-fearing behaviors. God is always faithful, and he will not let us down if we honor him as our first priority in the marketplace. In doing so, we will see successes in business, in life, and be a living testimony to others about God’s faithfulness.

Conclusion

In many respects, this research invites more questions than it provides answers. However, it shows many Christian professionals do desire to live integrated and holistic lives. It also appears to confirm that it is easier for the Christian business professional to follow the ways of the world in the marketplace, as it seems to offer more “success” than following God’s way as revealed in the Bible. The First Commandment is unambiguous: “And God spoke all these words: I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery. You shall have no other gods before me” (Exodus 20:1-3 NIV).

This commandment is equally relevant for the twenty-first century marketplace as it was for the ancient Israelites. When we put fear or success or secular concerns in a place of more importance than our worship of God of the Bible, we commit idolatry. The challenges of the First Commandment offers great opportunities for business professionals to lead as faithful witnesses to God’s wisdom and truth.

Notes

1 Kyle Idleman, Gods at War: Defeating the Idols that Battle for Your Heart (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2013).

2 David Miller, God at Work: The History and Promise of the Faith at Work Movement (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2007).

3Jerry Bentley, Herbert Ziegler, & Heather Streets-Salter, Traditions and Encounters: A Brief Global History (Boston, MA: McGraw Hill Higher Education, 2008), 163; and Peter Stearns, Cultures in Motion: Mapping Key Contacts and Their Imprints in World History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 36-37.

4Arland Hultgren elaborates on this idea by writing that “The rich fool is so preoccupied with gaining and maintaining his possessions that he is in fact idolatrous…[H]e places all his trust in his possessions [and] that is a form of idolatry, which is recognized as such in Jewish tradition.” See Arland Hultgren, The Parables of Jesus: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2004), 108.

5Christopher Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2006), 182.

6Gene Veith, God at Work: Your Christian Vocation in All of Life (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2002), 29.

7 Doug Sherman & William Hendricks, Your Work Matters to God (Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress, 1987), 86-88.

8 Veith, God at Work, 19.

9Lake Lambert III, Spirituality, Inc.: Religion in the American Workplace (New York, NY: New York University Press, Kindle edition, 2009), 170-172; 2686-2751.

10 Charles Sheldon, In His Steps (London, UK: Sunday School Union, 1898).

11 Ian Mitroff & Elizabeth Denton, A Spiritual Audit of Corporate America: A Hard Look at Spirituality, Religion, and Values in the Workplace (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1999).

12 C.W. Von Bergen & William Mawer, “Faith at Work.” Southern Law Journal (Fall 2008), 205-218.

13 Lambert III, Spirituality, Inc.

14 Miller, God at Work, 1499-1546.

15Some examples: William Diehl, Christianity and Real Life (Fortress, 1976); Richard Mouw, Called to Holy Worldliness (Fortress, 1980); Wally Armbruster, Let Me Out!: I’m a Prisoner in a Stained-Glass Jail (Multnomah, 1985); Doug Sherman, Your Work Matters to God (NavPress, 1987); Miroslav Volf, Work in the Spirit: Toward a Theology of Work (Oxford, 1991); William Diehl, The Monday Connection: A Spirituality of Competence, Af- firmation, and Support in the Workplace (Wipf & Stock, 1991); Mark Greene, Thank God It’s Monday: Ministry in the Workplace (Scripture Union, 1994); Max Stackhouse, et.al. (eds), On Moral Business: Classical and Contemporary Resources for Ethics in Economic Life (Eerdmans, 1995); James Childs, Ethics in Business: Faith at Work (Fortress, 1995); Thomas Smith, God on the Job: Finding God Who Waits at Work (Paulist Press, 1995); William Pollard, The Soul of the Firm (Zondervan, 1996); Michael Novak, Business as a Calling: Work and the Examined Life (Free Press, 1996); Alan Cox and Julie Liesse, Redefining the Corporate Soul: Linking Purpose and People (Irwin, 1996); and Stephen Graves and Thomas Addington, The Cornerstones for Life at Work (B&H Publishing, 1997).

16 Some examples: Laura Nash & Ken Blanchard, Church on Sunday, Work on Monday: The Challenge of Fusing Christian Values with Business Life, a Guide to Reflection (Joseey-Bass, 2001); Michael Budde & Robert Brimlow, Christianity, Incorporated: How Big Business is Buying the Church (Brazos Press, 2002); Thierry Pauchant, Ethics and Spirituality at Work: Hopes and Pitfalls of the Search for Meaning in Organizations (Praeger, 2002); Wayne Grudem, Business for the Glory of God: The Bible’s Teaching on the Moral Goodness of Business (Crossway, 2003); John Maxwell, Life@Work: Marketplace Success for People of Faith (Thomas Nelson, 2005); Neal Johnson, Business as Mission: A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice (IVP Academic, 2010); Mark Russell, The Missional Entrepreneur (New Hope Pub., 2009); and Steven Rundle & Tom Steff en, Great Commission Companies (IVP, 2011).

17 See, for example: Thomas Addington & Stephen Graves, A Case for Calling (Life@work) (Nashville, TN: Broadman and Holman Publishers, 1997), and Gary Badcock, The Way of Life: A Theology of Christian Vocation (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1998).

18 See, for example: William Diehl, The Monday Connection: A Spirituality of Competence, Affirmation, and Support in the Workplace (San Francisco: Harper, 1991), and Tom Nelson, Work Matters: Connecting Sunday Worship to Monday Work (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2011).

19 See, for example: Ken Eldred, The Integrated Life: Experience the Powerful Advantage of Integrating your Faith and Work (Montrose, CO: Manna Ventures, 2010), and Neal Johnson, Business as Mission: A Comprehensive Guide to Theory and Practice (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009).

20 See, for example: William Goheen, The Galtronics Story (Portland, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2004), and Jeri Little, Merchant to Romania: Business as Missions in Post-Communist Eastern Europe (Leominster, MA: Day One, 2009).

21 See Michael Cafferky, “Religious Beliefs and Models of Faith Integration at Work,” KnowledgeExchange @ Southern, accessed at http://knowledge.e.southern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?arti cle=1027&context=facworks_bus, for a preliminary empirical inquiry on this subject.

22 While it might appear difficult to draw meaningful conclusions from this research with such a small sample size, current anthropological research methodologies indicate that validity begins at twelve subjects and is best between twelve and twenty interviews for qualitative research. See Bernard, H. Russell, Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2011).

23 Idolatry can take many forms. The biblical narrative discusses idol worship, worshiping a false god instead of the God of the Bible (Galatians 4:8; 2 Kings 17:7-18). It also tells how some presume to know and worship the true God but at the same time worship one or more other gods (2 Kings 17:33; Isaiah 42:8, 48:11). In addition, the Bible explains that fear is indeed a form of idolatry (Matthew 10:28, 37; Proverbs 3:5). For additional biblical references on fear see, Deuteronomy 3:22, 31:6; Joshua 1:9; Psalm 23:4, 27:1, 34:4, 34:7, 55:22, 56:3, 91:1-16, 94:19, 118:6-7; Proverbs 12:25, 29:25; Isaiah 35:4, 41:10, 13-14, 43:1; Zephaniah 3:17; Matthew 6:34; Mark 4:39-40, 5:36, 6:50; Luke 12:22-26; John 14:27; Romans 8:38-39; Philippians 4:6-7; 2 Timothy 1:7; 1 Peter 3:14, 5:6-7; 1 John 4:18; and Revelation 1:17.

24 Richard Mouw, “Leadership and Bearing Pain.” Faith & Leadership (January 27, 2015). Accessed February 3, 2016. http:// www.faithandleadership. com/content/richard-j-mouw-leadership- and-bearing-pain?page=full&print=true.

25 http://www.springtemplebuddha.com/statue.

26See Bruce McCormack, Engaging the Doctrine of God: Contemporary Protestant Perspectives (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008). Also John Goldingay, Old Testament Theology (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2003).

27 David Hesselgrave, et.al. Missionshift: Global Mission Issues in the Third Millennium (Nashville, TN: B & H Academic, 2010), 27.

28 Stephen Neill, Creative Tension (London, Edinburgh House Press, 1959), 81.

29 Tormod Engelsviken, “Missio Dei: The Understanding and Misunderstanding of a Theological Concept in European Churches and Missiology,” International Review of Mission (92(4), 2003), 481-497.

30 James Scherer, “Missiology as a Discipline and What It Includes.” Missiology: An International Review (15(4), 1987), 507-522. The author personally rejects the idea that Missio Dei originated from the Trinitarian ideas of Karl Hartenstein and Karl Barth and instead argues that it originates in God’s being itself; therefore, mission is not a question of secondary significance to the Church, but rather is, or should be, a core theology of it.

31 Peter Boyer, “Frat House for Jesus,” The New Yorker Magazine (86(25), 2010), 52-61.

32 Leon van Rooyen, Theology and Life: The Study of God (Tampa, FL: Global Ministries and Relief, 2012), 7.

33 Scott Rae & Kenman Wong, Beyond Integrity: A Judeo-Christian Approach to Business Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2004).

34 Stephen Mansfield, The Search for God and Guinness: A Biography of the Beer that Changed the World (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2009).

35 Scott Kilman, “Tyson CEO Counts Chickens, Hatches Plan.” Wall Street Journal (9/7/2010). Accessed February 3, 2016, http://www.wsj.com/ articles/SB1000142405274870343160457546804124477305 2.

36 Chuck Williams, “Sunday Interview with Aflac CEO Dan Amos.” Ledger Enquirer (3/1/2014). Accessed February 3, 2016, http:// www.ledger-enquirer.com/news/local/article29322955.html.

37 “Stop over-taxing tourists, says Marriott boss Arne Sorenson as he eyes global growth,” Evening Standard (4/12/2013). Accessed February 3, 2016, http://www.standard.co.uk/ business/markets/stop-over-taxing-tourists-says-marriottboss- arne-sorenson-as-he-eyes-global-growth-8569958.html.

38 Oxford English Dictionary, “Business Ethics, n.” OED Online (Oxford University Press, 2016). Accessed May 20, 2016. http://0-www.oed.com.patris.apu.edu/view/Entry/25229 ?redirectedFrom=%22business+ethics%22#eid257220298.

39 John C. Maxwell, There’s No Such Thing as Business Ethics: There’s Only One Rule for Making Decisions (New York: Warner Books, 2003).

40 Peter Drucker, “What is Business Ethics?” The Public Interest (63, 1981), 18-36.

41 Hill, Just Business, 14.

About the Author

Hallqvist Albertson is the Founder and CEO of Hip Capital (www.HipCapital.com), a community of dreamers and doers who drive sustained, high-impact social change by utilizing a market- driven approach to business. Previously, Hallqvist ran an NGO in Asia focused on defending the rights of childrenat- risk and radically attacking the poverty, hunger, and injustice that enslave them. He is also a proven entrepreneur, having started and run a number of successful businesses. Hallqvist graduated with a bachelor’s degree with an international business focus from the University of Washington. He holds an MBA from Seattle University, an MA in theology from Fuller Theological Seminary, and a Ph.D. in informatics from Trinity College. More information about Hallqvist can be found at www.HallqvistAlbertson. com.