[By Jill Risner, Thomas Betts, and Bob Eams, 2017]

Abstract

This essay expands on existing research into the ways that businesses can value all their stakeholders by exploring a business’s responsibility to its customers. Businesses will go to great lengths to learn about their customers in an effort to forge lasting relationships with them – and capture the profitability that those relationships bring. This paper will explore areas of alignment and misalignment between the current treatment of relationships in marketing practices and a Christian perspective on relationships. The idea of “authentic relationships” is introduced as one way that businesses can redeem customer relationships with behaviors demonstrating honesty, respect, and love.

Introduction

A customer of a large retailer receives an email asking her to sign up to receive text messages from that retailer “because friends text.” The customer questions whether a store could really be her “friend.” The owner of a small auto repair shop decides to give one of his regular customers free labor on a brake job which causes the customer to experience a sense of loyalty and gratitude. When the customer picks up his car, he brings in donuts for the employees to enjoy. A retailer decides to implement a loyalty card program which allows them to gather data about customer preferences and shopping habits. This information is used to target ads to customers that are specific to their needs. Upon receiving these ads, some customers appreciate the personalization of the messages while others feel their privacy has been invaded.

Each of the above examples relates to a concept that is popular in the field of marketing, relationship. Often viewing long-term customer relationships as a path to increased profitability, companies invest large amounts of money into customer relationship management (CRM) programs that allow them to learn more about their customers, segment them into groups, and then target them with personal and relevant advertising messages.1 Christians will find the idea of relationship building to be consistent with biblical values. However, there are areas of alignment and misalignment between the modern marketplace’s view and a Christian worldview of relationships.

In this paper, we explore relationships in business and how Christians can foster them in a way that both supports current mainstream marketing practice and contributes to the redemption of a fallen business world. We start with a brief look at the evolution of and current use of relationships in marketing. Next, we will discuss a Christian perspective of relationships in marketing. We will then discuss the areas of alignment and misalignment between the marketing and Christian perspectives of relationship. Finally, we will introduce an approach to relationships, called “authentic relationship” that can be used to build on existing business practices that value relationships, but are more aligned with a Christian worldview. We close with some examples of how authentic relationship is applied in practice.

Marketing Perspective of Relationships

Over the past 60 years marketing has evolved from focusing internally on production and sales to externally on customer relationships.2 To manage the relationships businesses are building with their customers, marketers have increasingly relied on CRMs. CRM is “a strategic approach that is concerned with creating improved shareholder value through the development of appropriate relationships with key customers and customer segments.”3 Many companies view CRM as a key to increasing their long-term profitability.4 This focus on customers has also evolved into the recent increase in collection and analysis of “big data” available through consumer interactions. Businesses use big data to build customer relationships by learning the best way to market to them, the most effective way to handle purchase transactions, and successful strategies for attracting lost customers.5

Customers are one of an organization’s primary stakeholders as they are necessary for business survival and success.6 At times, marketing has become too focused on customers at the exclusion of other stakeholders (i.e., employees, suppliers, investors, and the community). There has been some movement toward stakeholder theory and stakeholder marketing, both of which expand the view of the responsibility of the organization to more broadly consider all stakeholders and how value can be created for multiple stakeholders simultaneously.7

While marketing theory considers stakeholders and a variety of financial and social outcomes through stakeholder marketing, most mainstream marketing practices remain focused on profit as the goal of relationship building. Marketing practitioners often justify the high cost of CRM systems with an expected return on investment (ROI) for the company. As businesses become more outcomes driven, marketers have increasingly relied on tangible measures such as profitability to justify their strategies.

Christian Perspective of Relationships

An exploration of Scripture reveals the goodness of relationships and God’s intention for humans to live in community. For example,

“Then God said, ‘Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness; let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth.’ So God created man in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them. Then God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply; fill the earth and subdue it; have dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves on the earth.’” (Gen. 1:26-28 NKJV)

In this passage, we are told that God created man in His own image. This included not just one man, but “the plurality of humankind, which includes a plurality of the sexes.”8 This community of men and women is connected to God’s own communal nature. When we are in a community, we are reflecting the nature of God and existing in a way that aligns with our own created nature.

The idea that we are created in God’s image means that we have a calling to carry out God’s intended purpose for us. That purpose is to reflect the nature of our Creator for the sake of all creation.9 The nature of our Creator is communal as the triune God is comprised of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. As men and women are created in the image of God, our calling is to reflect God’s communal nature by seeking perfect fellowship with one another, the created world, and the Creator. This fellowship will involve a reflection of the out-going, self-giving love of God as we seek to love others with their benefit in mind. Scripture also tells us that relationships involve not only a love for others, but a love for ourselves as well. The book of Matthew tells us, “Therefore, whatever you want men to do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets.” (Matt. 7:12). Thus healthy relationships involve care for both parties. A person in a relationship has a responsibility to protect herself from being unfairly taken advantage of by the other.10 The Christian view of relationships has a communal nature.

Christian Perspective on Business Relationships

A substantial body of work exploring business from a Christian perspective has developed over the past two decades, providing the groundwork on which to build a better understanding of relationships. Hagenbuch states that marketing must build relationships if it is to be called a Christian vocation.11 He points to Scripture passages such as 2 Corinthians 5:18-19 which describe our call to reconciliation: “Now all things are of God, who has reconciled us to Himself through Jesus Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation, that is, that God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself, not imputing their trespasses to them, and has committed to us the word of reconciliation.” Hagenbuch argues that living a life of reconciliation is at the core of all Christian vocation. Reconciliation, which is focused on “restoring, building, and maintaining strong relationships”12 must therefore be supported by marketing efforts in order for marketing to be considered a Christian vocation.

Van Duzer argued that the true purpose of business consists of: 1) providing meaningful work to people and, 2) providing beneficial goods and services to society.13 With this perspective, the role of profit is to sustain the operations of a business, but not to serve as its end goal. Wong and Rae made a distinction between the use of relationships in mainstream marketing practice where businesses attempt to create deep emotional connections with customers with the goal of getting them to make more purchases and the Christian perspective of relationships, which they term “authentic relationships.”14 Wong and Rae described authentic relationships as relationships “built on dignity, trust, mutual respect and true concern for others.”15 In these relationships, customers are treated as valued friends.

A faith-based perspective of relationships leads us to conclude that businesses should show care and concern for relationships with all stakeholders. Businesses should not focus on the benefit of one stakeholder at the sacrifice of others. Marketers should fully embrace the concept of stakeholder marketing and pursue the betterment of all stakeholders to the greatest extent possible. However, in this paper we focus on the important primary stakeholder group of customers. The successful management of customer relationships will ultimately lead to benefits not just for customers but for all stakeholders.

Some Clarifications

Some debate has occurred over whether or not a customer can actually enter into a relationship with a brand. Relationships involve interdependence in which partners jointly affect, define, and redefine their relationship so the question of whether or not a brand can interact with a customer should be explored.16 Kotler defines a brand as being a promise made to customers to deliver a fulfilling experience at a certain level of performance.17 The brand is a representation of a promise made by people within an organization to the customer

By “living the brand” those people work to carry out that promise. In this way, the brand serves as a conduit through which the employees of a company engage in a relationship with their customers. With this understanding, we assume that even though customers build what some would call relationships with brands, the relationship is actually being built between people, the customer and the employees of the company. This brand conduit serves as a unifying element to add consistency to the interactions that one customer might have with multiple people within a company as they interact with the company, its products, and its brand in various settings. We assume that whether we are discussing customers building relationships with brands, products, or companies, the actual relationship is occurring between people (the customer and those within the company) and sometimes the interactions of that relationship are carried out through marketing strategies such as branding.

Even in instances where marketing actions such as emails or website are automated, we hold that a relationship between the customer and a representative of the company is occurring. An automated computer process must be set into place by a person who is deciding how the details of that automation will occur. That person’s decisions about the automation will impact the customer in either a positive or negative way. For example, a person may establish a program for a bank where customers are automatically reminded when they have a payment due, thus helping customers manage their finances more effectively. Alternatively, a person may program a digital game in a way that is addictive and offers in-game purchases to continue playing, thus encouraging customers to spend money and time in unproductive ways. In both scenarios relationships are occurring between two people through the medium of technology.

Relationships are defined by a series of interactions over time between individuals in which each interaction “affects the future course of the relationship, even if only by confirming the status quo.”18 Based on this definition, there are certain customer interactions that would not be considered a part of the relationships that businesses are establishing. For example, if an individual is on vacation and stops at a local, independent gas station to buy a drink, that person is not in a relationship with the owner of the gas station because the two only interact on one occasion. Similarly, if a company places an ad in a magazine and that ad is viewed by an individual who does not become a customer of the company, that person is not in a relationship with the company. This paper focuses on interactions that occur between the representatives of a company and their customers over time. Again, these interactions often occur through the medium of a brand or other marketing mix elements (product, price, place, and promotion strategies).

Areas of Alignment and Misalignment

There are areas where modern marketplace practice aligns well with a Christian perspective of relationships. Marketing facilitates exchange relationships. Clark and Mills define an exchange relationship as one that occurs when the “parties involved understand that one benefit is given in return for another benefit.”19 They contrast this with communal relationships in which each person has a concern for the welfare of the other and benefits are given with no expectation of receiving anything in return (such as a relationship between close friends or family members).20 As an example, if we helped a friend move, we would not expect payment for the benefit given. In fact, we may be hurt or confused if our friend offered to pay us. Both exchange and communal relationships are needed for a society to function. Exchange relationships are needed because they provide motivation to businesses. Because the norms of exchange relationships dictate that one benefit be given in return for another, businesses have been motivated to develop a wide variety of products to meet customer needs. Also, because of exchange relationships people can specialize and then trade for the goods and services they need. Communal relationships are needed in a society because they allow for needs to be met in individuals who are unable to return the favor.21

The customer focused approach of marketers also supports the idea of providing for society’s needs. Customer relationship management is based on the idea that in order to succeed, businesses must understand customer needs and respond to them. The idea of meeting customer needs aligns well with one of Van Duzer’s stated purposes of business, the provision of beneficial goods and services to society.22 Stakeholder marketing requires the development of relationships that include shared values and exchanges of value between multiple stakeholders, not just customers, in order to produce the desired financial and social outcomes that are valued by primary and secondary stakeholders.23 At their core, marketing relationships allow for exchange to occur, providing for the needs of our society.

The fact that marketing practitioners are embracing relationships is positive. However, sometimes a good thing is being misused. In the field of marketing the relationships that are built with customers are valued because they bring better company performance. Marketing textbooks promote the idea that relationships with customers are a means that can be used to achieve greater marketing efficiency and effectiveness and ultimately improved profitability.24 The literature in CRM theory and big data consistently emphasizes the outcome of gaining power and leverage over customers in order to maximize profitability or increase shareholder returns.25

Drawing on the distinction made by Clark and Mills between exchange and communal relationships, we assert that businesses are focused on building exchange relationships with customers (in which they receive a specific return for the efforts they put into relationship building) under the guise of building communal relationships. For example, when a company asks a customer to sign up to receive text messages from the company “because friends text,” the company is presenting itself as a friend to the customer. A friend is someone whom we enter into a communal relationship with and by its communal nature, there is an expectation that the parties have genuine concern for the other’s welfare with no expectation of a return being received for a benefit given. However, relationship marketing efforts are measured in terms of how much value customers return to the company. This is more aligned with the expectations of exchange relationships. Furthermore, if customers do not return sufficient value to the company, efforts to maintain the relationship are often ended. This raises several concerns including the fact that businesses are being dishonest and customers could possibly get hurt or taken advantage of in the process.

Karns confirms this concern about the mainstream business perspective of exchange when he discusses the contemporary paradigm of exchange.26 The contemporary paradigm of exchange sees economic interactions as a means by which people seek their self-interested personal happiness. Marketers are encouraged to foster long-term relationships with the goal of achieving long-term profitability. The central values influencing this paradigm are materialism and consumption.

A biblical perspective of exchange relationships reveals inconsistencies between the Christian themes of relationships, love, and covenant and the contemporary exchange paradigm. The current exchange paradigm elevates self over others and uses relationships as instruments. We are called to love others, which involves a self-sacrifice, but with the current exchange paradigm businesses choose to “love” certain customers more than others based on their calculated profitability. Also, businesses often break covenants with their customers when they become unprofitable, abandoning previously held commitments.27 There is clearly a misalignment between the current exchange paradigm which is self-focused and a Christian perspective of relationships which is others-focused. Below we will propose a path to bring these two perspectives into better alignment.

Authentic Relationship

As stated above, marketers value relationships, but they are often built with customers to achieve the end goal of profit. We believe that a marketer’s interactions with his or her customers should involve more than a focus on profit. Profit is necessary for the operation of a sustainable business and must be considered when making marketing decisions. However, there is something more that should be considered: a concern for reconciliation and relationship.

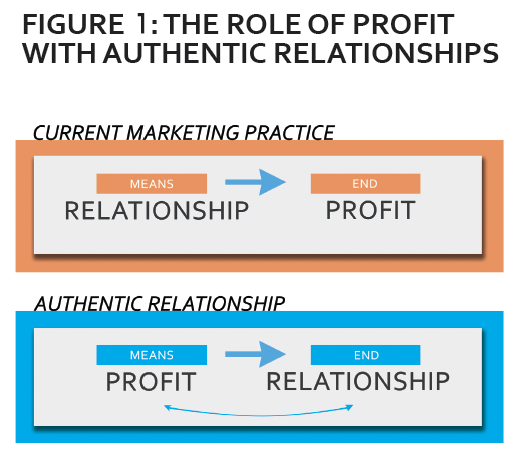

We propose an approach that uses profit to make the necessary investments to pursue and sustain relationships (see Figure 1). We distinguish this from the current marketing paradigm of relationships by referring to it as the “authentic relationship” approach, borrowing it from the language of Wong and Rae.28 Authentic relationship marketing repositions caring for customers’ needs as an end rather than a means and views profitability as something that allows this process to occur. With the authentic relationship approach marketers seek to use all of a business’s creative power and innovative capacity to serve customers in a way that is profitable and sustainable.29 In relation to Clark and Mill’s distinction between exchange and communal relationships, an authentic relationship approach incorporates both. An exchange relationship does exist, but the communal relationship is also honestly pursued and is the goal of the interaction.

The authentic relationship approach involves showing customers respect, honesty, and love.

30 We respect our customers because they are God’s image bearers (Gen. 1:27). Made in the image of God, our customers deserve the same respect that we would give our Heavenly Father. Respect should be given to all customers, not just those who promise a high ROI. God does not show favoritism (Acts 10:34), nor should we. The Bible also commands us to be honest (1 Pet. 2:1; Ex. 23:1-3) which is the second element in building authentic relationships. Being honest with customers involves being transparent, open, and generous with communication whenever possible, even if some of the power we could hold over them needs to be given up. Finally, authentic relationships require that we love our customers. We are to love God and love our neighbor as we would ourselves (Matt. 22:37-39). Also, our love must involve action (1 John 3:18), not just words. By approaching customers with respect, honesty, and love, Christians in the modern marketplace can build on the positive aspects of existing marketing practice while contributing to the transformation and redemption of business. Doing so also allows Christians to pursue relationships with all stakeholders that are communal in nature, seek perfect fellowship rather than self-serving exchange, and provide adequate levels of protection or self-care in order to assure sustainability of the organization.

Authentic relationship marketing repositions caring for customers’ needs as an end rather than a means and views profitability as something that allows this process to occur.

Authentic relationships often are reciprocal. In a reciprocal relationship customers seek to show honesty, respect, and love to the company that has shown these things to them. They do this through actions such as showing brand loyalty, providing positive word of mouth, and not abusing liberal company policies. Although this is not the end goal of the exchange, this reciprocal relationship often leads to increased profit for the company, creating a continuous loop of mutual benefit (see Figure 1). This also means that the outcomes of both current marketing practice and an authentic relationship approach may look the same from the outside, yet marketers’ intentions may be different. While the intentions of a marketer are not always observable, these intentions are still God-honoring and can often be experienced in subtle ways within the space of customer-marketer interaction.

Authentic Relationship in Practice

To gain a better understanding of the authentic relationship approach, it is helpful to explore what this model looks like in practice. In this section of the paper we will discuss the process-oriented nature of authentic relationships, how certain organizational structures/designations can foster authentic relationships, how to manage the needs of various stakeholders while pursuing authentic relationships, and some practical steps that individuals can take to adopt this approach to marketing.

Authentic relationship building is a process. Having authentic relationships is something that businesses strive toward and therefore it is something that is best measured in terms of degrees rather than something that is achieved or not achieved. Pursuing authentic relationships is similar to the Christian faith. There is no finish line. It is a process that we work to grow in daily. Additionally, because of the complexity of organizations, the authentic relationship approach may be embraced at an organizational, divisional, team, or just individual level. Many businesses operate differently in their various divisions and departments. While some individuals in a company may be building authentic relationships with their customers, others may not. Of course, a company’s goal should be to have consistency in processes across the organization, but in reality, this is often not the case.

How an organization is structured and its established mission both affect the pursuit of authentic relationships. We pointed out that when adopting an authentic relationship approach, profit shifts from being the end to a means by which relationships are pursued (see figure 1). Some have argued that once a business organizes as a corporation they have a legal obligation to pursue profit as the end goal. The board of directors of a corporation does have a fiduciary responsibility to all stakeholders, which includes the shareholders. However, when a company incorporates, if they desire, they do have the option of explaining in the articles of incorporation that the ultimate purpose of their company is not to make a profit. An example of a company that did this was the AES Corporation which made its priority specific company values rather than profit.31

For companies that are already incorporated, an alternative to consider as a means of communicating the role of profit to investors is to become a certified benefit corporation or B Corp. B Corps are committed to using business as a force for good to create enduring prosperity for all stakeholders.32 When investors see that a corporation has the B Corp certification it communicates to them that while profit will be considered when making business decisions, it is not the exclusive goal of the company. For example, one of the outcomes that B Corps seek to achieve is to increase credibility and build trust with customers.33 Becoming a B Corp is not synonymous with adopting an authentic relationship approach, but it is a way to communicate with investors that profit is not the exclusive goal of the company.

Outdoor equipment retailer, REI, has avoided incorporation altogether and instead has chosen to organize as a cooperative or co-op, a structure under which the company was originally founded in 1938. A co-op is “a business or organization owned by and operated for the benefit of those using its services. Profits and earnings generated by the cooperative are distributed among the members, also known as user-owners.”34 Co-ops are established with a focus on service and member benefits rather than profit. Remaining a co-op allows REI to focus on the long-term benefit of the co-op members (who are customers), workers, and their communities, rather than company investors.35 The co-op model aligns well with the guiding principles of authentic relationship. Ideally, co-ops are based on truly caring interactions and support between the organization and the customers/members.

Stakeholder theory and stakeholder marketing both hold that when organizations consider the proper role of profit and the allocation of valued outcomes it is helpful to consider what all stakeholders (shareholders, suppliers, employees, and even customers) desire as a good return on the value they give a company and the risk they assume in partnering with them. The beliefs and values of different stakeholder groups can affect the desired return. There are situations where stakeholders are willing to accept a lower level of return because they believe in what the company is providing or stands for. For example, some employees working in Christian organizations accept lower pay because they believe in the mission of their employer. Even customers may decide to pay more for products if they support a business’s mission. Businesses must recognize that stakeholder relations are interdependent. When one stakeholder receives benefits, this will ultimately translate to benefits for other stakeholders, creating an upward cycle of positive outcomes for all stakeholders.36 For example, by paying suppliers well, a firm is able to provide quality products for customers to purchase. Increased purchases allows employees to be paid well so that the firm can hire high quality workers who will serve their customers well, etc.

Authentic relationships thrive when the parties in the relationship are focused on the betterment of the other. However, this ideal exchange does not always exist. There are times, for example, when customers exploit businesses for their own personal benefit. This is especially likely to happen when the company is focused on the betterment of the customer and the customer is focused on his own self benefit. When this occurs, it is important for the business to not enable the customer in his exploitation. To do so would be to abandon the business’s responsibility to sustain itself profitably. As an example, REI’s return policy used to allow customers to exchange or return items purchased at the store for the lifetime of the item. Unfortunately, some customers exploited the policy, returning heavily used items to the store for cash. REI found that a small group of co-op members were making a large number of returns in a way that they believed was not sustainable for the co-op. Because of this they changed their return policy to only one year.37

There are businesses owned by Christians that use the principles of respect, honesty, and love to cultivate authentic relationships. Chick-fil-A is a well-known example. Chick-fil-A is guided by a corporate purpose “to glorify God” and “have a positive influence” on everyone they interact with.38 This results in a guiding philosophy of service which is carried out by “treating customers like friends” and serving “communities like neighbors.”39 This philosophy is not just the belief system of a handful of people, but a part of the company’s culture in which all members of the organization strive to serve others in consistent ways. Evidence of this can be seen in small ways, such as when employees respond to customers with gratitude. Any time a customer says “Thank you” to a Chick-fil- A employee he or she would respond with eye contact, a smile, and a statement like, “It’s my pleasure!”

Dee Ann Turner of Chick-fil-A points out that the unique culture of Chick-fil-A is built and reinforced in three important ways. First their talent selection process focuses on choosing people with the appropriate character, competency and chemistry to fit in and contribute to the culture. Second they nurture talent by being truthful and respectful in stewarding talent in the organization. Finally, they engage their customers or guests in the culture so that they all can share the feeling of being treated with honor, dignity and respect.40 The results speak for themselves as Chick-fil-A continues to lead all limited service restaurants by a large margin in customer satisfaction while retention of corporate staff and franchisees both exceeded 95% for nearly 50 years.41

Concluding Remarks: Authentic Relationships

Company owners who would like to adopt an authentic relationship approach are encouraged to review their existing mission, policies, and practices while considering what the stated end goals of their businesses are. Often mission statements emphasize caring for customers, but practices are driven by profit. Practitioners should reflect on ways that the two can be brought into better alignment.

Individuals who do not have the authority to make large changes at their companies can focus on the influence that they do have. While interacting with customers and other stakeholders of the business, employees can reflect on whether their actions could be described as respectful, honest, and loving. Often when discussing the ethics of various marketing situations with students in class, we hear students respond, “Well, I wouldn’t want it to be done to me, but it is great from a business perspective!” These two ideas should not be separable. What is good for the business must also be good for the customer. A great question to ask when interacting with customers comes back to the Golden Rule: “Would I want to be on the receiving end of this customer interaction?”

Ultimately, a lot of the distinction between an authentic relationship approach and a profit driven approach lies in our personal intentions. The actions of companies using these different approaches can often look the same. So, the first step in implementing an authentic relationship approach is to examine ourselves and the purpose that is driving our decisions. Christians must have the courage to lead by example (1 Pet. 5:2-3), and work toward creating a company culture that values authentic relationships with all stakeholders.

Notes

1 Susan Fournier, “Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research (24(4), 1998), 343.

2 See Theodore Levitt, “Marketing Myopia,” Harvard Business Review (82, no. 7/8, 2004), 138-149; Ajay K. Kohli and Bernard J. Jaworski, “Market Orientation: The Construct, Research Propositions, and Managerial Implications,” Journal of Marketing (54(2), 1990), 1-18.; and John C Narver and Stanley F Slater, “The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability,” Journal of Marketing (54(4), 1990), 20-35.

3 Adrian Payne and Pennie Frow, “A Strategic Framework for Customer Relationship Management,” Journal of Marketing (69(4), 2005), 168.

4 Susan Fournier and Jill Avery, “Putting the ‘Relationship’ Back Into CRM,” MIT Sloan Management Review (52(3), 2011), 63.

5 “Big Data: What It Is and Why It Matters,” SAS, accessed February 9, 2017, http://www.sas.com/en_us/insights/big-data/ what-is-big-data.html

6 R. Edward Freeman, Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach (Marshfield, MA: Pitman Publishing Inc., 1984).

7 G. Tomas M. Hult, Jeannette A. Mena, O.C. Ferrell, and Linda Ferrell, “Stakeholder Marketing: A Definition and Conceptual Framework,” Academy of Marketing Science (1, 2011), 44-55.

8 Stanley J. Grenz, Theology for the Community of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2000), 175.

9 Ibid., 177.

10 Alexander Hill, Just Business: Christian Ethics for the Marketplace, 2nd ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2008), 53-58.

11 David J. Hagenbuch, “Marketing as a Christian Vocation: Called to Reconciliation,” Christian Scholar’s Review (38(1), 2008), 83- 96.

12 Ibid., 87.

13 Jeff Van Duzer, Why Business Matters to God and What Still Needs to be Fixed (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2010), 151-168.

14Kenman L. Wong and Scott B. Rae, Business for the Common Good (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press Academic, 2011), 211-229.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid., 344.

17Philip Kotler, forward to Kellogg on Branding, eds. Alice Tybout and Tim Calkins (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005), ix.

18 Robert A. Hinde, “On Describing Relationships,” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (17, 1976), 3.

19 Margaret S. Clark and Judson Mills, “The Difference Between Communal and Exchange Relationships: What It Is and Is Not,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin (19(6), 1993), 686.

20 Margaret S. Clark and Judson Mills, “Interpersonal Attraction in Exchange and Communal Relationships,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (37(1), 1979), 12.

21 Clark and Mills, “The Difference Between Communal and Exchange Relationships”, 686.

22 Van Duzer, 152.

23 Hult et. al., “Stakeholder Marketing”, 44-55.

24 Roger J. Best, Market Based Management: Strategies for Growing Customer Value and Profitability, 5th ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009), 6.

25 Werner Reinartz, Manfred Krafft and Wayne D. Hoyer, “The Customer Relationship Management Process: Its Measurement and Impact on Performance,” Journal of Marketing Research (41(3), 2004), 295.

26 Gary L. Karnes, “A Theological Reflection on Exchange and Marketing: An Extension of the Proposition That the Purpose of Business Is to Serve,” Christian Scholar’s Review (38(1), 2008), 97-114.

27 Ibid.

28 Wong and Rae, 211-229.

29 Jill R. Risner, Robert H. Eames, and Thomas A. Betts, “Common Grace and Price Discrimination: A Motivation toward Authentic Relationship,” Journal of Markets and Morality (18(1), 2015), 99-118.

30 Ibid.

31 A detailed discussion of this company and its founding principles can be found in Dennis W. Bakke, Joy at Work: A Revolutionary Approach to Fun on the Job (Edmonds, WA: Pear Press, 2006), 1-40.

32 Ryan Honeyman, The B Corp Handbook: How to Use Business as a Force for Good (Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2014), 13.

33 Ibid., 26-28.

34 “Cooperative,” US Small Business Administration, accessed February 9, 2017, https://www.sba.gov/starting-business/ choose-your-business-structure/cooperative

35 “About REI,” REI Co-op, accessed February 9, 2017, https:// www.rei.com/about-rei.html

36 John Mackey and Raj Sisodia, Conscious Capitalism (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

37 Kirsten Grind, “Retailer REI Ends Era of Many Happy Returns,” The Wall Street Journal (September 15, 2013), accessed at https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB1000142412788732454900 4579068991226997928

38 “Corporate Purpose,” Chick-fil-A, accessed February 9, 2017, https://www.chick-fil-a.com/About/Who-We-Are

39 Ibid.

40 Dee Ann Turner, It’s My Pleasure (Boise, ID: Elevate Publishing, 2015).

41 “ACSI Restaurant Report 2016,” American Customer Satisfaction Index, June 21, 2016, www.theacsi.org

About the Authors

Jill Risner is an assistant professor of business at Calvin College and co-founder with her husband of a marketing consultation and graphic design business. Jill has a DBA with a concentration in marketing from Anderson University.

Jill Risner is an assistant professor of business at Calvin College and co-founder with her husband of a marketing consultation and graphic design business. Jill has a DBA with a concentration in marketing from Anderson University.

Thomas Betts is a professor of business at Calvin College. Previously he spent 25 years in marketing and management in the publishing industry. Thomas has an MBA from Western Michigan University.

Thomas Betts is a professor of business at Calvin College. Previously he spent 25 years in marketing and management in the publishing industry. Thomas has an MBA from Western Michigan University.

Robert Eames is a professor of business at Calvin College and director of the Calvin Center for Innovation in Business. He has over 20 years of experience in marketing and as an executive in the insurance, advertising, and office furniture industries. Robert has an MBA from the University of Wisconsin.

Robert Eames is a professor of business at Calvin College and director of the Calvin Center for Innovation in Business. He has over 20 years of experience in marketing and as an executive in the insurance, advertising, and office furniture industries. Robert has an MBA from the University of Wisconsin.