[By David Miller and Timothy Ewest, 2017]

“Whatever you do, work heartily, as for the Lord and not for men” Colossians 3:23 (ESV)

Introduction

In many church circles, mere mention of the word “stewardship,” particularly on “Stewardship Sunday,” brings but one thought to mind… the annual “Pledge Sunday” when the faithful are asked to tithe and commit to a financial pledge for the upcoming year. While that certainly is important and has its rightful place in the life of the church, equating stewardship to annual giving diminishes the use of a powerful word. The dictionary defines stewardship as the “managing of something, especially the careful management of something entrusted to one’s care.”1

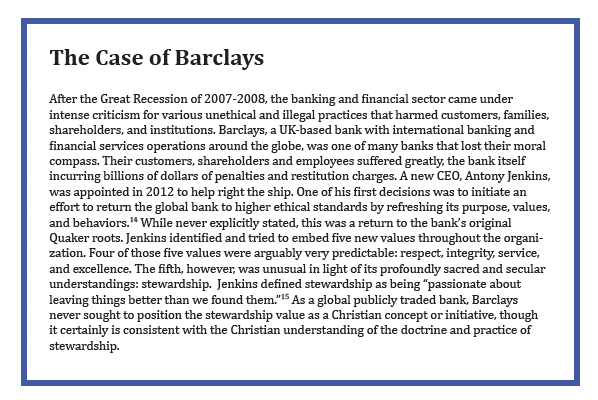

The term stewardship is not a uniquely Christian concept, and indeed it has many commercial and historical roots outside the church. For example, stewardship is also commonly used in reference to land management, financial investment, administration of public utilities, and even disease management. Since 1980, the use of the word stewardship has more than doubled in published materials.2 Today, the concept of stewardship has also found a growing application by business leaders and the organizations they lead as an idea to guide their actions as they enrich the lives of their employees and surrounding communities, while simultaneously caring for the environment and making robust profits. As the example of Barclays Bank later in this paper demonstrates, it seems the practice of stewardship is on the increase by leaders in businesses, initially emerging out of the 1990’s (labeled the “busy decade” where work became unhealthy and unbalanced3), one of the most robust economic eras in American history.4

Stewardship Today

As a means to return balance and focus for the American manager, in 1993 Peter Block reintroduced and popularized the idea of stewardship for business managers. Block’s book, Stewardship: Choosing Service over Self Interest, asked managers to practice stewardship, which entails individual leaders who take personal responsibility for their own actions and the actions of organizations. Block’s book captured a rising sentiment within corporate America,5 for a return to using the strength of profitability to help employees, the planet and communities flourish. As many organizations and their leaders were already embracing or practicing personal and organizational stewardship, others joined anew, creating a revolution.

Recent research on those who hold the Chief Executive Officer or other executive positions reveals a trend for these professionals to guide their organizations towards sustainability, with up to 64% of these executives moving in that direction.6 Many of these executives have a core set of personal values that accent caring for the world and people regarding their jobs as a sacred trust.7 The result has been the creation of numerous environmentally and socially responsible organizations, which do so without jeopardizing robust profits. The concept of stewardship has also found corresponding support within the academic community, with an increasing emphasis on researching the ideals, methods and realities of organizations which are good stewards. Even the United Nations has undertaken implementing the ideals found in stewardship – directing efforts to strengthen business operations and ensure the principles are taught to business students so future leaders are equipped to practice stewardship as they manage organizations.8

It is becoming common for companies, and those who manage them, to endeavor to be responsible stewards of their organization’s conduct and its impact on wider society and stakeholders. This is often referred to as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The CSR movement is broad and energizing with well-known brands dominating the headlines. Companies such as Apple, Amazon, Starbucks, Berkshire Hathaway, Disney, Southwest Airlines and 44 other companies are ranked by Forbes as being responsible corporate citizens.9 These companies endeavor to serve the wider society not just through the goods and services they provide, but also by taking responsibility for their employees, communities, and environmental wellbeing, as part of a continued commitment to increasing return on investment.

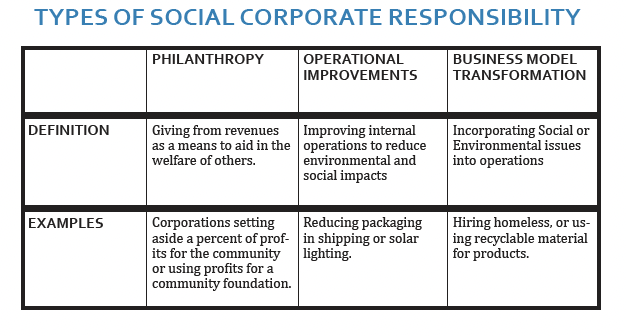

A group of Harvard researchers studying the activities of companies identifiable as socially responsible found three distinct types of practice (see chart). The first were companies that practiced philanthropy; the second were companies that improved operations to lessen social or environmental impacts; and the third pursued total operational transformations. The third group actually incorporated the social or environmental issues into their revenue generating production as a means to make profit.10

Whether it is referred to as stewardship, corporate social responsibility, or otherwise, today companies have multiple commercial motivations to think beyond quarterly returns, e.g., building a strong brand, enhancing social standing, increasing employee motivation, explaining market share, acting ethically, ensuring future sustained growth, or simply being good corporate citizens. The emergence and growth of CSR has deep resonances with the Christian ideal of stewardship and may even share some similar motivations, but the Christian’s primary motivation for stewardship is very particular and grounded in Biblical teachings.

Christian Stewardship

Christian Stewardship was a command given by God before the fall to guide humanity’s purpose in work. God commanded that humans work with creation to help build flourishing societies, and do so as a means to honor God who is the sustainer and owner of all things. Right after He finishes his work, God “placed humans in the garden” and commanded that humans should, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (Genesis 1:28).

Tim Keller’s church and ministry in New York City is known for intentionally helping Christians connect their everyday work to God’s work. Keller hears in these early passages from Genesis a call from God to build human society as a means to make humans flourish. Keller asserts that God’s principal command to humans was to subdue the earth, which he suggests was not a license to exploit nature, but rather a trusteeship to build harmony within creation.11 This central doctrine of stewardship which is entrusted to us is, in the Christian tradition, also called “Co-regency.” The term emphasizes an important dimension: that we work with God, and also work as God worked in this initial creative act, mirroring or imaging God.12

Coregency does not suggest that humans are equal to God, rather that they seek to imitate God, as they are created in the image of God. Therefore, as God invested himself in his creation, so Christians are to imitate God and invest themselves in creation, using their gifts to create, plant, grow and harvest and thus bring out the goodness God placed into creation through their work. Primarily God commands Christians to be a coworker in creating harmony within creation, to help creation flourish. God as owner of all things wants his good purposes known in his creation, and so this command has not changed even after the fall of humankind. While the fall of humanity has increased human’s burden, it has not diminished their purpose.

The Christian practice of stewardship can be found in the earliest expressions of Christianity in America. Examples in our history are not hard to find: Quakers, Moravians, and Puritans are but a few examples of early Christians in America who took responsibility, and used their organizations to help humans flourish within the new world. These early American Christians considered the building of these early societies as cities of light and in turn established long standing businesses that were intended to help communities flourish. These businesses were community minded, and dedicated to service and supporting the churches’ mission.13 Today, Christian business leaders have the same commitment to help their employees, communities and the created order to flourish. Barclays Bank is such an example [see box: The Case of Barclays].

It All Belongs to God

Most organizations are rightly motivated to protect and enhance shareholders’ interest. It might surprise some that Christians should also protect and enhance shareholders’ interest, in part because they are agents of and trustees for the owners. But also, playing out the metaphor, Christians consider God to be their majority shareholder.

They believe God owns their business and from these core convictions their workplace stewardship behaviors and practical business actions should flow. Each of these practical activities are a means to use and express the gifts God endowed each person with, as a means to bring harmony to the created order, to make it flourish, and in turn imitate the creator God by serving creation on God’s behalf. Christians join God through their life’s work, including the practices of business by inventing, developing, growing, and profiting.Inventing is creating products and services to ease suffering, extending life, reducing resource consumption through operational efficiencies, curing diseases through technological innovation or creating compelling expressions of art. Inventing happens when Christians use their personal gifts to create new harmonies in the existing created order, bringing out and celebrating the good in creation as a means to honor God. Famous composers such as Bach, Handel and Gaupner, whose compositions are still as compelling and engaging today as when they were written centuries back, all signed their creative works with Soli Deo Gloria, “Glory to God alone.”16

Developing can be represented by initiating new internal or external ways of recognizing human flourishing, including starting community outreach activities or addressing human rights issues. Christians use their personal gifts to develop their inventions, creating organizational structures for workers, supervisors, managers, and leaders to flourish. An example of this is John Tyson, chairman of Tyson Foods. He introduced new core values and related policies, including that Tyson Foods “strives to be a faith friendly company.” This means they welcome and embrace each employee’s faith tradition as a valued part of that person’s identity.17 Through this development, Tyson has become a marketplace leader seeking to constructively address human rights issues of respecting faith in the workplace.

Growing can be seen when leaders coach employees, build great structures, expand into new markets, address social needs at a large scale or find a better design for an existing product or service. Christians use their personal gifts to practice growing when they help individuals, organizations and the environment live to their full designed potential. Many times it works from a vision of what the organization, person or community can become. In Barcelona, Spain, the Sagrada Família is one of the greatest structures; its construction, begun in 1882, is only now nearing completion. The estimated cost for the construction will be in excess of 570 million Euros. The Sagrada Família is arguably one of the most beautiful basilicas in the world, and has employed thousands of workers, and mesmerized thousands of tourists, but its initial design was offered by one person of faith, Antoni Gaudí. Gaudí’s design is still alive and growing, pulling together resources from the Barcelona community.18

Profiting can be seen whenever leaders responsibly reap the benefits of their collective work in the marketplace, often by producing satisfactory financial profits and returns. Yet Christian thought teaches that profiting cannot be measured by financial or monetary indicators alone. Creating a healthy culture, employee engagement and good will, the enhancement of brand image, the solving of a community problem or tackling long-standing environmental issues within their supply chain are also profitable outcomes. Christians active in such endeavors benefit through inventing, developing, growing, and ultimately profiting from organizational and marketplace activity done in a God-pleasing way. This process of stewardship also leads Christians to be generous and cheerful philanthropists to share the fruits of their labor. For example, after a successful career of innovation and growth in the energy business, Bob McNair’s Baptist faith led him to direct a significant portion of his wealth to support health care and education through the McNair Foundation19, ensuring everyone shares in the benefits of success.

Today, Christians engage in inventing, developing, growing, and profiting activities as a means to use their gifts to make the created order flourish. Christian stewards, acting out of their love and devotion to God, seek to honor God in and through their work. However, this longstanding doctrine of stewardship is missing something when compared to generations past – an emphasis on the second coming of Christ.

Christians consider God to be their majority shareholder. They believe God owns their business and from these core convict ions their workplace stewardship behaviors and practical business actions should flow.

All Things New

Historically, the Christian practice of the doctrine of stewardship has been attentive not only to the work God has given us for our lifetimes, but also with a view toward the life to come. Christians were once anchored theologically to the doctrine of the end times (eschatology), believing that through the work of the Church in the world they could help usher in the Kingdom of God (amillennialism). In the past, Christians understood the world they were in was rich with blessing and goodness, but because of the Fall, human work would be difficult and done “by the sweat of your brow” (Gen 3:19). Christians in the past worked for today, but also worked with a view of the world to come. They had their minds set on “things to come” (Colossians 3:10). What has been lost from the doctrine of stewardship, as practiced by many of today’s Christians, is forgetting the final goal, a new creation.

“He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and there will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain, for the former things have passed away. And the One seated on the throne said, “Behold, I make all things new.” Revelations 21:4-5

Christians, when they act as stewards, are modeling and predict ing the initial goodness that was intended to be in the created order, and the goodness that is to come when Christ returns

After the fall God’s creative power did not abate. He returned to his fallen creation and continued to employ his creative powers to redeem and restore this newly fallen creation. The grand narrative is that God is using his people to help restore the fallen world and remind us of the new creation that is coming. Christians, when they act as stewards, are modeling and predicting the initial goodness that was intended to be in the created order, and the goodness that is to come when Christ returns.20

Conclusion

The MBA dictum of decades past that the sole purpose of a company was to maximize profits is increasingly seen as a failed theory, even threatening the very health of the company, if not democratic capitalism as a whole. There are a growing number of secular organizations in the competitive marketplace that take responsibility to care for the planet, people and profit. Corporate executives, whether Christian or not, realize that their customers and employees are concerned not only with making money, but also with doing well in the world. Yet corporate leaders and business owners who are Christians do so with a different set of motives. The Christian businessperson is expressly motivated by the doctrine of stewardship, and its teachings of inventing, developing, growing, and profiting. Further, they realize that neither they nor the shareholders ultimately own the company; God does. They are holding these work related assets, resources, and gifts in trust for God, and God’s promised coming kingdom. Christians are called by God to be stewards of the workplace and through it to demonstrate care for their neighbors and the environment, even as God carries out His plan of redemption and restoration for humanity and the world.

Notes

1 https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stewardship

2 According to Google Books Ngram Viewer.

3 Mary Costello, Still Full of Sap: Reflections on Growing Older (iUniverse, 2005).

4 Alan B. Krueger & Robert Solow (eds), The Roaring Nineties: Can Full Employment be Sustained? (Russell Sage Foundation, 2002).

5 Peter Block, Stewardship: Choosing Service over Self-interest (2nd ed) (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2013).

6 Terry Yosie, P. J. Simmons, & Sam Ashken, Sustainability and the Modern CMO (Corporate Ecoforum and World Environment Center, November 2016), accessed http://www.corporateecoforum. com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Sustainability-andthe- CMO_FINAL.pdf. Or See the 19th Annual Global CEO Survey (January 2016), accessed https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/ceosurvey/ 2016/landing-page/pwc-19th-annual-global-ceo-survey. pdf.

7 Research indicates that organizations which practiced sustainability had top management visibly supportive of their organizations’ sustainability practices. They did so because of deeply embedded personal core values. See Jena Wirtenberg, et. al. (eds.), The Sustainable Enterprise Fieldbook: When it All Comes Together (Oxford: Greenleaf Publishing, 2008). Also see Sheila Bonini & Anne-Titia Bove, Sustainability’s Strategic Worth: McKinsey Global Survey Results (McKinsey & Company, 2014), Accessed http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainabilityand- resource-productivity/our-insights/sustainabilitys-strategic- worth-mckinsey-global-survey-results.

8 See Morela Hernandez, “Toward an understanding of the psychology of stewardship,” Academy of Management Review (April 2012), 37(2), 172-193.

9 https://www.forbes.com/sites/karstenstrauss/2016/09/15/ the-companies-with-the-best-csr-reputations-in-the-world-in- 2016/#55e99ed27506.

10 Kasturi Rangan, Lisa Chase, & Sohel Karim, “The truth about CSR,” Harvard Business Review (Jan-Feb. 2015), 93(1/2), 40-49.

11 Tim Keller, Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work (New York: Penguin Random House, 2012), 56.

12 This is referred to as the functional image of God, See Richard Middleton, The Liberating Image: The Imago Dei in Genesis 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2005).

13 Timothy Ewest, “Sociological, Psychological and Historical Perspectives on the Reemergence of Religion and Spirituality within Organizational Life,” Journal of Religion and Business Ethics, 3(2) (2015):1-14. See also David Miller & Timothy Ewest, (2013) “Faith at Work (Religious Perspectives): Protestant Accents in Faith and Work,” In Handbook of Faith and Spirituality in the Workplace, ed. Judi Neal (New York: Springer, 2013), 69-84.

14 Co-author David W. Miller serves as an external ethics advisor to Barclays, though all information reported here is public domain.

15 https://www.banking.barclaysus.com/our-history.html, accessed May 17, 2017.

16 See John Butt, The Cambridge Companion to Bach (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1997), and Michael Allen, Reformed Theology (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010).

17 See http://www.tysonfoods.com/we-care/faith-in-the-workplace. Also David Miller & Timothy Ewest, “A New Framework for Analyzing Organizational Workplace Religion and Spirituality,” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 12(4) (2015), 305-328.

18 Valerie Gladstone, “Architecture: Gaudí’s Unfinished Masterpiece Is Virtually Complete,” New York Times, August 22, 2004.

19 Chang, L. N. D., College of Science Annual Report 2009-2010.

20 Stanley Grenz & John Franke, Beyond Foundationalism: Shaping Theology in a Postmodern Context (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2000).

About the Authors

David W. Miller joined the faculty of Princeton University in 2008, serving as the founding Director of the Princeton University Faith & Work Initiative. His signature class is “Business Ethics & Modern Religious Thought.” His previous appointment was at Yale, where he served as the Executive Director, Yale Center for Faith & Culture, and taught at both the Divinity School and School of Management. Before receiving his Ph.D. in ethics, he spent 16 years in senior executive positions in international business and finance, including eight years in London. He is the author of the critically acclaimed and best-selling book, God at Work: The History and Promise of the Faith at Work Movement (Oxford University Press). Alongside his work at Princeton, David serves as an advisor to CEOs in matters pertaining to ethics, values, leadership, and faith at work.

David W. Miller joined the faculty of Princeton University in 2008, serving as the founding Director of the Princeton University Faith & Work Initiative. His signature class is “Business Ethics & Modern Religious Thought.” His previous appointment was at Yale, where he served as the Executive Director, Yale Center for Faith & Culture, and taught at both the Divinity School and School of Management. Before receiving his Ph.D. in ethics, he spent 16 years in senior executive positions in international business and finance, including eight years in London. He is the author of the critically acclaimed and best-selling book, God at Work: The History and Promise of the Faith at Work Movement (Oxford University Press). Alongside his work at Princeton, David serves as an advisor to CEOs in matters pertaining to ethics, values, leadership, and faith at work.

Timothy Ewest is Associate Professor of Management at Houston Baptist University and a Visiting Research Scholar at Princeton University’s Faith & Work Initiative. His research interests include issues surrounding the integration of faith at work and prosocial leadership, with a number of published journal articles and books on leadership and faith at work. Tim consults with organizations focusing on strategy, ethics and leadership development, and his prior work experience includes 11 years in ministry, 15 years in higher education and 5 years in corporate America. Tim is an ordained minister in the Christian & Missionary Alliance and holds a Master’s Degree in Theology from Wheaton College, a Master’s degree in Theology from Regent University, and an M.B.A. and Doctorate in Management from George Fox University.

Timothy Ewest is Associate Professor of Management at Houston Baptist University and a Visiting Research Scholar at Princeton University’s Faith & Work Initiative. His research interests include issues surrounding the integration of faith at work and prosocial leadership, with a number of published journal articles and books on leadership and faith at work. Tim consults with organizations focusing on strategy, ethics and leadership development, and his prior work experience includes 11 years in ministry, 15 years in higher education and 5 years in corporate America. Tim is an ordained minister in the Christian & Missionary Alliance and holds a Master’s Degree in Theology from Wheaton College, a Master’s degree in Theology from Regent University, and an M.B.A. and Doctorate in Management from George Fox University.