[By Randy Beavers, Denise Daniels, Al Erisman, & Don Lee, 2018]

Abstract

While the unintended consequences and high pace of change associated with technology will change the nature and types of our interpersonal relationships, Christian theology provides a lens through which we can evaluate these changes. In this paper we outline some theological principles that undergird our understanding of what God intends for relationships, as well as ways that our relationships are either consistent or inconsistent with God’s intentions in terms of healthy and unhealthy relationships. We then discuss ways in which communication technology can amplify both positive and negative aspects of relationships, providing examples from the workplace. We classify the impact of technology on relationships through one of four categories: connectivity, closeness, engagement, and/or reciprocal understanding. Finally, we summarize our conclusions about ways that Christians could think about and engage with technology, and we discuss some areas where future research would be useful.

Introduction

For centuries of human history, relationships have been rooted in presence. What a person said and did in a variety of situations were factors in shaping a relationship. A person was brave, bold, kind, caring, collaborative (or the opposite of these) and this was evident in what that person said and did in the presence of others. For the most part, relationships occurred face-to-face. Historically, technology supplemented face-to-face relationships, for example through letter writing.

Recently, technological advancement has enabled new methods of interpersonal interactions, changing our understanding of what a relationship is and how we engage in it. For example, instead of requiring two people to be in the same place at the same time in order to interact, technology allows people to engage while in different places, or to communicate at different times. It has opened opportunities for many more relationships, allowed global teams to work together from different locations, allowed access to new talent or new customers, and created unprecedented collaboration across the world. These changes provide positive opportunities for us to create and extend relationships, but they also create significant challenges. Because technology is changing at such a rapid pace, we are often unaware of the ways in which it affects us and our interactions with others.

Assuming that relationships and technology are both under God’s dominion, it is particularly important for Christians to be attentive to how technology might impact our view of and communication with others, as well as how we might utilize technology to be aligned with God’s purposes for us. We need to ask how technology influences relationships and to what extent these impacts facilitate or hinder God’s intent.

Technology is “the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency in every field of human endeavor,” according to Jacques Ellul.1 Often, though not always, it is associated with the application of science to achieve some practical end. The term “technology” has often been used to refer to information technology or digital devices, but the subject is much bigger. There are implications of technology that we should be aware of if we want to understand the role of technology in our lives. We will highlight two: one that applies to technology generally, and one specific to information technology.

First, technology has unintended consequences.2 A technology created to solve one problem might later solve a different problem. The automated teller machine (ATM) was created to shorten the lines inside a bank, but it ultimately resulted in the advent of 24-hour banking when it was moved outside the bank building. Conversely, a technology used to solve one problem can create a different problem. The automobile improved the ability to move from place to place in a timely way, but also introduced pollution, traffic accidents, and so forth. The same technology used for good (driving to see friends) can be used for evil (bank robber’s getaway car), and various technologies can be combined to create something completely new and altogether un-envisioned by their creators. For example, the computer chip, a modem, the internet, and security technologies are combined to make online commerce possible. While we will never eliminate unintended consequences, we can evaluate what might go wrong in the use of technology, and seek to mitigate against the potential misuse of the technology. Certainly after the evidence of misuse is recognized, we can seek to manage it. For example, debating something in email may lead to divergence of understanding, and a face-to-face conversation may be better to resolve a misunderstanding.

Second, information technology in particular has a very high pace of change. Moore’s law says that every two years the number of transistors per square inch will double.3 Roughly interpreted, this means that every two years any device dominated in cost by the transistor will either drop by a factor of two for the same performance, or double in performance for the same price. When combined with unintended consequences discussed above, this means that completely new ways of doing things can appear almost overnight. This has two important consequences: 1) Since people absorb change at different rates, there will be some people who quickly get on board the new way of doing things, while others (for reasons of priority, cost, or learning) are left behind. This suggests we should make relationships a significant factor in deciding whether or not to use a given technology. Rather than use video conferencing because we can, we should ask what might be missing in how we relate to each other, and seek other solutions to fill in; and 2) Each new opportunity opens the possibility for exploitation that can be used by those with nefarious intent. There is a time lag, sometimes significant, between when someone discovers a way to exploit the technology and when others uncover what is going on. Toxic mortgage-backed derivatives and the polluting effect of Volkswagen diesel engines are illustrations of this.

While the unintended consequences and high pace of change associated with technology will change the nature and types of our relationships, Christian theology provides a lens through which we can evaluate these changes. In this paper we outline some theological principles that undergird our understanding of what God intends for relationships, as well as ways that our relationships are either consistent or inconsistent with God’s intentions. We then discuss ways in which communication technology can amplify both positive and negative aspects of relationships, providing examples from the workplace. Finally, we summarize our conclusions about ways that Christians could think about and engage with technology, and we discuss some areas where future research would be useful.

Theological Values Undergirding Relationships and Technology

Before we turn our attention to a discussion of relationships and the ways in which technology can influence them, we need to start with an overview of some theological principles that help us understand God’s intent for both technology and relationships. While there are a large number of Christian scriptures that have implications for technology and relationships, in this section we focus on three principles from the creation narrative that are critical, as well as some additional concepts emphasized in the New Testament.4

Implications from Creation

First, we learn from the opening chapters of Genesis that humans are created in God’s image: “[In] the image of God he created them. Male and female he created them.”5 While this can mean many things, most agree that it places particular worth on humankind. Thus in relationships we should seek to recognize the particular worth – the imago Dei – of another person.

A second theological principle derived from the creation narrative with implications for relationships is that each member of the Godhead is in relationship with the other members of the Trinity. We see this allusion when God says, “Let us make man in our image…”6 A foundational view of God in Scripture is one of being in relationship – we see the three persons of the Trinity interacting and communing with one another. So we too are designed to be in relationship with God and with each other. When God sees that Adam is alone since no animal was like him, God says “It is not good,”7 and creates for Adam a partner in Eve. To the extent that technology allows us to communicate better and to develop and maintain relationships, it may be one avenue through which we can live out God’s purposes for humanity.

The third theological principle is derived from the Creation Mandate (sometimes referred to as the Cultural Mandate), where God tells Adam and Eve to “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”8 Later God gives Adam the responsibility to name the animals. These commands require that humans continue creative activities that God began. We are invited to use our creative energies to cultivate the raw materials of creation into something new. While there may be obvious implications of the Creation Mandate for reproduction and agricultural cultivation, many theologians have also understood it to apply to every aspect of humanity’s creative impulses, from physical artifacts such as making clothes, building houses, and creating art, to organizational policies and practices, to creating government structures9 – and yes, even creating technology. God could have created a computer tree from which we gather hardware and software, but instead chose to provision the world perfectly, and invited us into the creative process. The human creation of technology is one of the ways in which we reflect God’s design for humanity. In the same way that God’s creativity produced an order that sustained human life, trees that were “pleasing to the eye and good for food,”10 human creativity too can contribute to order, be aesthetically pleasing, and useful in meeting human needs.

Other Biblical Implications

One result of sin in the Garden was the breaking of relationships, both between humans and God and between humans themselves. We see this clearly in Genesis 3 as Adam blames Eve and God for the sin (“that woman you gave me” he says to God). But the Bible is very clear that relationships remain important, rooted in the fact that other humans are image bearers, even in the presence of sin.11 Further, Jesus’s teachings on healing broken relationships12 and the importance of another person13 underscore our need to prioritize the role of relationships.

We must recognize that not every aspect of our relationships or creativity will align with God’s purposes. Nonetheless, it is important to see that from the very beginning, the importance of relationships and creativity are rooted in who God created us to be. It is also important to note that as followers of Christ we are to be agents of reconciliation in the world,14 and this includes bringing reconciliation to our relationships. Because we are designed for good relationships, yet we are living in a world marred by the fall, the relationships that we build and maintain, will have both healthy and unhealthy components. A vital step is not to attempt to “go it alone” as an individual. Wise counsel can be a great support to helping us overcome our own blind spots; and in Matthew 18 we are reminded when we get stuck in a relationship issue, we should engage others. In the next section we discuss some factors that determine the health of relationships.

Healthy relationships recognize the dignity of others, are characterized by appropriate levels of trust, and reflect reciprocity.

Healthy and Unhealthy Relationships

What determines whether a relationship is healthy or not? This is where Christian theology can provide helpful guidance. As Scripture highlights, humans are created in the image of God. We are God-breathed soul inhabitors, made for life beyond the world that we know. C.S. Lewis (1941) famously said, “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations – these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub and exploit.”15 Healthy interpersonal relationships are marked by a recognition that others are intrinsically and eternally valuable, regardless of what they do or do not do for us. When we view others as important simply because of who they are, rather than objectifying and viewing them as instrumental to our own ends, we both honor God and the person made in God’s image.

Appropriate levels of trust also characterize healthy interpersonal relationships. This trust needs to be mutual so far as possible16 and built on demonstrating trustworthiness. Healthy relationships are marked by a level of personal sharing and vulnerability appropriate to the particularities of the relationship. For example, sharing intimate details about oneself with a spouse or very close friend who holds that information in confidence is healthy. Sharing the same information with a neighborhood acquaintance, who then shares it with others, might be quite unhealthy. In the latter case, the depth of the relationship is not commensurate with the information shared; there may be inappropriate vulnerability not supported by the reality of the relationship. In other words, there may be unfounded assumptions about trust with the acquaintance. Intimate relationships could be unhealthy in an opposite way. Being unwilling to share personal vulnerability with anyone – including close friends or family members – is a marker of low trust levels and an unhealthy relationship.

Of course, appropriate levels of trust are predicated on the trustworthiness of the two parties in a relationship. Trust is formed by a cognitive process through which we evaluate the ability, benevolence and integrity of another in order to discern who is trustworthy.17-18 In other words, one’s trustworthiness inspires trust.19 Note, however, that trust can be formed in an unhealthy manner in situations where there is deception resulting in a false belief that the trustee is trustworthy. Relationships are unhealthy when beliefs about trustworthiness are distorted by lies, deception, and accusations.

Finally, healthy relationships are reciprocal. One side is not always giving and the other taking, but rather there is a back and forth that characterizes the relationship. Unhealthy relationships are one-sided. One person makes assumptions about the other person in terms of their level of engagement and commitment to the relationship that are not true. This may occur when one person makes demands on the other without ever providing anything in return. It could also occur when one person assumes a level of connection or intimacy with the other that is not shared by the other.

In a business setting, healthy relationships are fundamental to the culture and performance of an organization, but the business setting itself sometimes works against healthy relationships. Due to the pressures of business, it is easy to treat another person as a means to get something done, rather than a person made in the image of God. Further, in a business setting, we are often put together with people we might not choose for a relationship, requiring a stronger commitment to gain mutual understanding. Finally, technology may filter our perceptions of others, reducing them to a response, a voice, or a message, and making it more difficult to see them as a whole person. Meeting face-to-face, having meals together, and learning non-work-related things about another person brings them to life, allowing us to see others as more fully human. Exploring how trust and relationships are a part of the bigger story of organizational culture is important and has a business value.20

We are made in God’s image, designed for relationship, and designed to create. Because of the Fall our relationships may be either healthy or unhealthy. Healthy relationships recognize the dignity of others, are characterized by appropriate levels of trust, and reflect reciprocity. In the next section we explore how our creative impulses have resulted in technologies that can both enhance and damage our relationships.

Impact of Technology on Relationships

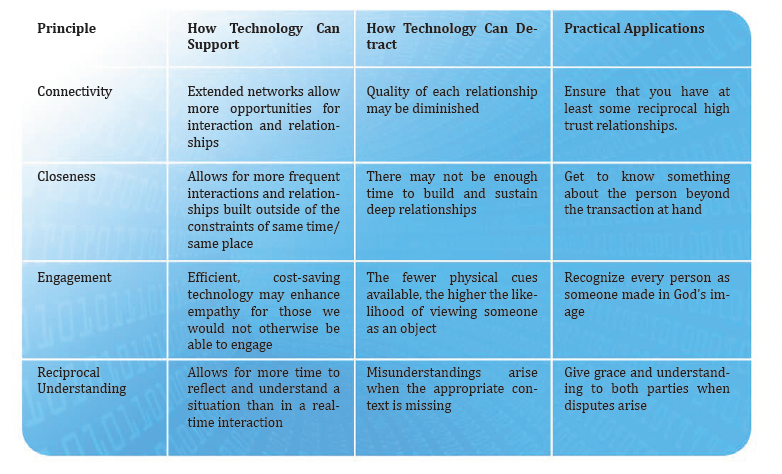

Technology has an amplifying effect on interpersonal relationships. Technology is neither an unmitigated good nor evil, but it is powerful, and its consequences can result in good or bad outcomes. Technology can amplify the health or flaws in relationships, pushing them to become either more or less healthy. In order to explore this amplification effect, we discuss the impact of technology on four characteristics of relationships:21 Connectivity, Closeness, Engagement, and Reciprocal Understanding.

Connectivity

First, relationships are based on connectivity, the level to which one can gain access and interact with another. Two or more counterparts need to be connected in order to interact and build a relationship. Through communication technology, humans can build and maintain relationships regardless of location and time, synchronously and asynchronously. Various modes of communication, such as email exchange, blogs, online forums, and texting, give us the opportunity to extend conversations and thus maintain relationships even if communication only occurs sporadically. Acquaintances can be made more quickly than before, and more acquaintances can be made than before. Social network platforms (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.) and virtual online communication tools (Skype, FaceTime, various video conferencing tools) have changed the way we interact, enabling us to build relationships in new and different ways.22 Through social media technology we can become acquainted with another in an instant by a click of the mouse or a tap on a screen. Our networks extend through our current connections, allowing us access to a constellation of others with whom we can start potential relationships. We can become acquainted with people far beyond our neighborhoods through use of technology, something that would not have been possible without technology.

This increase in connectivity may be positive in that it allows us to sustain relationships with friends or co-workers who are no longer in geographic proximity. This initial connection through technology often leads to face-to-face connections. One recent study showed that users of digital technology heavily frequent public spaces such as cafes, restaurants, and religious centers, and consequently might be more likely to have offline interactions.23 In this respect, communication technology allows us more opportunities to express our God-given design for relationship.

While many more interpersonal interactions are possible due to technology, the quality of these relationships may be diminished since technology does not provide us with any more time than we had in the past. The consequent challenges are much deeper than those in the relationships we had without technology: Do we have the time with another person to understand who that person really is beyond the transaction we are engaged in? Do we have time to build the trust and understanding of our neighbor or co-worker when there are so many competing relationships? Is the relationship reciprocal, or are we simply eavesdropping on another person’s life via social media? Increased connectivity may also imply a level of trust with someone else that is no longer based on our personal experience with them. Moreover, it allows those we do not know to reach us. When we receive a message from someone we do not know, how do we understand the validity and the intentions from the conveyed message? While increased connections due to communication technology allow us more opportunity for relationships, they may also diminish the extent to which we view others with dignity, lead to lack of reciprocity, and result in unfounded assumptions about trust.

Closeness

Second, closeness depicts the mental or physical distance between one another in an interaction. Technology might enhance the sense of closeness between two people by allowing for communication and interactions that are more frequent. For example, technology that provides high fidelity and allows people to interact in different places at the same time (such as Skype or FaceTime) might enhance their closeness to each other. Such interactions may cultivate trust and better allow us to see the image of God reflected in the other person. On the other hand, increased speed and the enhanced ability to reach more acquaintances through communication technology may also have negative effects on relationships. Communication technology may hinder one’s dedication of time to build and maintain relationships due to the frequency of communication one is expected to make on a regular basis – for example, the volume of e-mails, instant messages, and posts that are expected to be replied and responded to. In addition, people may have unequal access, knowledge, and motivation to use rapidly changing technology, resulting in relational diminished closeness between users and non-users of the technology, or even isolation between the different populations (e.g., between generations, populations of social economic status, regions). The type of technology may also affect the sense of closeness people experience. Particularly, when interactions occur at different times and in different spaces, people may not be able to catch the value-based cues that are usually transferred in same time/same place interactions, which can affect the perceived trustworthiness of the other. For example, texting, which is increasingly replacing face-to-face and telephone conversation for younger people,24 may not convey adequate emotion or nuance necessary for the full development of trust. In the era of social networking, one can have hundreds of “friends,” and tens of thousands of second level relationships. Nevertheless, the number of connections does not imply closeness; and in fact, some data suggests that those with large numbers of connections in their social networks may actually have weaker interpersonal relationships – or less closeness – than those who have fewer connections in their social networks.25

Engagement

Third, there is a sense of engagement between counterparts in relationships. Engagement conveys the attention one gives to a communication interaction. A person may be fully engaged with all senses in a synchronous, faceto- face interaction, but less engaged in an asynchronous e-mail communication. As anyone who has ever taught an online class knows, the level of engagement when interactions are technology-mediated can be hard to gauge. The typical indicators of engagement, such as eye contact, facial expressions, and body language, are less available. When the interaction occurs at different times, such as with email communication or via Google docs, engagement is yet harder to determine. Engagement is impacted by whether the interaction occurs synchronously or asynchronously. Issues of trust become difficult to evaluate: Are they who they say they are? When we are less engaged with another, it becomes easier to think of them as an object rather than fully human. One of the significant implications of this objectification is that empathy and compassion toward the other are often diminished, resulting in behaviors toward them which minimize their humanity. Some evidence suggests that online interactions are more likely than face-to-face interactions to elicit interpersonal hostility.26 On the other hand, other research indicates a positive correlation between some types of social media use (chatting and Facebook) and empathy.27 The contrasting research findings suggest that the relationship between technology use and empathy is complex and will require more exploration before we have a clear picture of the interaction.

Ellul argues that efficiency is a core value of all technologies. 28 Businesses often focus on the efficiency and cost savings associated with technology, ignoring the longer-term effects of technology’s impact on our view of human dignity, trust, and reciprocity. Healthy relationships require a commitment of time and effort to build and maintain. Because technology can make communication “quick-and-easy,” it may also prevent the formation of meaningful relationships. The ease of interaction that technology provides may make the relationship more transactional rather than “covenantal.” For example, technology can help us schedule more meetings and enable us to make each meeting shorter. However, this process of efficiency focuses on the tasks to be achieved, reinforcing the idea that the person with whom we are engaged is a part of the task, rather than an agent in a covenantal relationship. Efficiency does not leave room for the casual conversation away from the formal agenda, where you may really be able to understand another person. The challenge is to embrace the value of technology without losing the healthy aspects of relationships that are central to our identity as image bearers of God.

Reciprocal Understanding

The extent to which there is reciprocal understanding is another characteristic of relationships. Misunderstanding others is always possible, and can be amplified by technology. Consider the situational factors that can lead to misunderstanding between two people: language, culture, background, and environment all play a part in building and maintaining relationships. A low level of reciprocal understanding depicts a situation where counterparts are communicating with each other but lack the understanding of the other person’s world. For example, engineers may talk about the functional meaning of the various components of the product, whereas finance people might talk about the cost of the same components. A lack of appreciation for or understanding of the other’s perspective might cause a misalignment in communication (“not being on the same page”), potentially putting the relationship between the engineers and finance people at risk. On the other hand, a high level of reciprocal understanding may depict a situation wherein relationships are built and maintained despite the differences of situational context in which communication occurs.

To what extent does technology influence an understanding of the situational context? On the one hand, since the content of a message often requires context for full understanding, it is easy to see how misunderstandings can develop when context is stripped away through technologies that minimize contextual cues. In may be difficult to communicate context and develop trust without “living life together” and knowing the person beyond the message. On the other hand, in some cases technology may allow for more time for reflection and understanding than face-to-face or real-time interactions. When narratives need to be interpreted, elaborated, or explained, the time and space distance that technology can allow could be beneficial. In these cases technology can help us contextualize the conversations and thus help us have a better understanding of the communicator’s intent, increasing the trustworthiness and meaningfulness of a relationship. With more frequent communication an individual’s motivations and interpersonal style would be more evident.29 Therefore, asynchronous communication via technology, compared to an instantaneous, physical face-to-face interaction may give people more time to help contextualize the communication by clarifying, interpreting, and explaining their perspectives.

A better understanding of another’s intentions and emotions may increase the experienced trust in the communication, which in turn helps build and maintain relationships. Francis Fukuyama drew this conclusion: “If people who have to work together trust one another, doing business costs less…By contrast, people who do not trust one another will end up cooperating only under a system of formal rules and regulations which have to be negotiated, agreed to, litigated, and enforced, sometimes by coercive means.”30 In some cases communication technology will work against trust development, but in other cases it can be used to enhance it.

Implications Moving Forward

Throughout history, technology has revolutionized communication and has required humankind to respond and adapt to how we move forward as a society. Examples include the printing press, telegraph, and telephone. However, “the internet and mobile phone have disrupted many of our conventional understandings of ourselves and our relationships, raising anxieties and hopes about their effects on our lives.”31 In this paper, we contribute to the conversation by including a theological perspective and combining research from communication, technology, and business. Even when we believe we have resolved how to do effective communication fostering healthy relationships, we know that a new technology will come along and challenge our framework once again. As we gain comfort with a technology, it could change our effective use.

Technology will continue to change rapidly and we cannot expect to predict the practical consequences that may result. Nonetheless, there are theological principles that can guide us: Everyone we interact with, whether face-to-face or via technology, is made in the image of God. God desires us to have healthy relationships, marked by appropriate trust and reciprocity. Our calling to be agents of reconciliation should motivate us to continue to discover ways that technology can be used to enhance and support relationships, and to avoid ways that it undermines these same relationships. There are four aspects of relationships that are affected by technology: connectivity, closeness, engagement, and reciprocal understanding. We summarize the opportunities, challenges, and practical applications associated with each in the attached table.

We have seen that technology opens up many types of communication that can enhance or hurt relationships. A common danger in practice is to make simplistic rules about using or not using technology in communication. Consider the following rule: “Never email a colleague from your office, but rather walk down the hall and talk with them.” If the purpose of the communication is to solve a misunderstanding, that may make sense. If the purpose is to communicate the time of a meeting the next week, the interruption from talking with a colleague would be an intrusion for both of you. Thus, it is important to think carefully about the nature of the communication and use the technology that works the best for the communication at hand. Rather than hard and fast rules regarding technology, we need to utilize our God-given and Holy Spirit-enabled conscience to contribute to human flourishing. The best of these decisions are not just made individually, or even “between me and God,” but rather in community. This helps us get beyond our own self-justification and lack of self-awareness.

In an earlier era, Forrester and Drexler 32 introduced a way of using the various modes of communication for the effective performance of a team, focusing on face-to-face communication for trust building, using same time/different place tools for clarification of goals and objectives, and finally doing individual work with updates communicated through asynchronous communication. As technologies become more capable, each needs to be examined for its ability to support the different motivations for communication, and used appropriately. For example, could we effectively build trust through a holographic discussion or a video chat session, or does trust require physical presence with someone? In addition, the cost of interaction in a relationship must be considered. Working with a colleague on the other side of the world, we might know that face-to-face would be desirable but travel costs may make it prohibitive.

Future Directions

There are many considerations we have not covered or only hinted at in this paper. Throughout the preceding sections we have referenced relationships primarily between two individuals. But we also have relationships with non-human entities, including with our pets, with inanimate objects (e.g., cell phones, Roomba vacuums), with companies, and with artificial intelligence (e.g., Siri or Alexa). What principles should guide our interactions in such non-interpersonal relationships? This may become increasingly important as technology increasingly blurs the line between objects and people.

We have not discussed the ways in which organizational contexts might shape the impact of technology on relationships. For example, the position someone has in an organizational hierarchy might make the use of technology more or less appropriate in their interactions with others. Similarly, the role of the individual with whom you are interacting (e.g., customer, supplier, or community member) may also influence the type of technology that is appropriate, or the extent to which it ought to be used. We are not aware of research that has examined the faith commitments of those in organizational leadership and the extent to which such values influence the decisions that are made about using technology. For example, are Christians any more likely than others to draw on theological principles in considering how to use technology? Future studies may well add value to the discussion of the impact of technology on relationships by considering various and nuanced organizational contexts.

Finally, there are a number of ways in which technology may influence individuals, which we have not discussed. For example, there is empirical research demonstrating the impact of “screens” on children’s brain development, and a number of questions raised about the potentially addictive nature of some technologies. Should there be limits associated with our use of some technology? Does this depend on age, gender, personality, etc.? Does the Scriptural mandate for Sabbath apply to our use of technology? That is, if technology is a tool that helps us to work, then limiting its use one day per week would be consistent with the concept of Sabbath keeping.33 Is there a difference between productive and consumptive use of technology in terms of its impact on the individual? Does the way in which a technology is being used have a bearing on its value? If so, are there criteria that can guide our assessment of it and decision making about its use?

Overall, we hope that our discussion of how technology influences relationships and how theological principles can guide our evaluation of these influences might provide helpful guidance to those in organizational settings who must make decisions about using technology. We also recognize that there are many things we still do not know about technology and how it might influence relationships. It is our hope that future work can expand our understanding of the interaction between technology and relationships in a world of rapid and constant change.

Notes

1 Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, tr. John Wilkinson (New York: Knopf Doubleday, Vintage Books, 1964). Ellul made the distinction between technique (using the stated definition) and technology (which he defined as the study of technique) but for our purposes we will use technology for both.

2 Edward Tenner, Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge of Unintended Consequences (New York: Knopf Doubleday, 1996). Tenner more fully develops the case for the unintended consequences of technology.

3 Mike Golio, “Fifty Years of Moore’s Law,” Proceedings of the IEE (103(10), October, 2015), 1932-1937.

4 For a more thorough discussion of theological values undergirding relationships see Denise Daniels & Al Erisman, “Relationships at Work,” presented at the Christian Business Faculty Association annual meeting, October 19-21, 2017, San Diego, CA

5Genesis 1:27

6 Genesis 1:26

7 Genesis 2:18-25

8 Genesis 1:28

9See Andy Crouch, Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (Westmont, IL.: IVP, 2008) for a fuller description of the implications of the Cultural Mandate.

10 Genesis 2:9

11 Genesis 9:6 and James 3:9

12 Matthew 18

13 Matthew 18:6, Luke 17:2, Matthew 25:40

14 2 Corinthians 5:18, “All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation.”

15 C.S. Lewis, “The Weight of Glory,” Sermon delivered in the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Oxford; reprinted in Theology (November, 1941). Retrieved from: https://www.verber.com/ mark/xian/weight-of-glory.pdf

16 Romans 12:18

17 Mayer, Roger C., James H. Davis & F. David Schoorman, “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust,” The Academy of Management Review (20(3), 1995), 709-34. Accessed at http://www.jstor.org/stable/258792.

18 J.D. Lewis & A. Weigert, “Trust as a Social Reality,” Social Forces (63(4), 1985), 967-85.

19 Fernando Flores & Robert C. Solomon, “Creating Trust,” Business Ethics Quarterly (8(2), 1998), 205.

20Both David Gill and James Heskett make the case that trust is critical to building a healthy organizational culture, and that culture ultimately influences organizational outcomes; see David W. Gill, It’s About Excellence: Building Ethically Healthy Organizations (Executive Excellence Publishing, 2008), and James Heskett, The Culture Cycle: How to Shape the Unseen Force that Transforms Performance, (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Press, 2012).

21 Organizational communication scholars have described various characteristics of relationships, but as far as we are aware,they have not been compiled in any systematic or commonly recognized way. For example, the Fundamental Interpersonal Relationships Orientation (FIRO) is a theory and measure of an individual’s desired and expressed levels of inclusion, control,and openness in relationships; see W.C. Schutz, FIRO: A Three Dimensional

Theory of Interpersonal Behavior (New York, NY: Holt,Rinehart, & Winston, 1958). Also Brito et.al. describe group relationships in terms of their levels of communal sharing, authority ranking, and equality matching; see Rodrigo Brito et.al., “The Contexts and Structures of Relating to Others: How Memberships in Different Types of Groups Shape the Construction of Interpersonal Relationships,” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships

(28(3), 2010), 406-431. We are using the four characteristics of connectivity, closeness, engagement, and reciprocal understanding to describe relationships in this paper.

22 Robert Weiss & Jennifer P. Schneider, Closer Together, Further Apart: The Effect of Technology and the Internet on Parenting, Work, and Relationships (Carefree, AZ: Gentle Path Press, 2014).

23 Keith Hampton, Lauren F. Sessions, & Eun Ja Her, “Core Networks, Social Isolation, and New Media: How Internet and Mobile Phone Use is Related to Network Size and Diversity,” Information, Communication & Society (14(1), 2011), 130-155.

24“Texting Becomes Most Popular Way for Young People to Stay in Touch.” The Telegraph (December 3, 2012). Retrieved on 1/30/2018 from http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/ news/9718205/Texting-becomes-most-popular-way-foryoung- people-to-stay-in-touch.html.

25 Stephanie Tom Tong, Brandon Van Der Heide, Lindsey Langwell & Joseph Walther, “Too Much of a Good Thing: The Relationship Between Number of Friends and Interpersonal Impressions on Facebook,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (13(3), 2008), 531-549.

26See for example, E.A. Jane, “Your a Ugly, Whorish Slut—Understanding E-bile,” Feminist Media Studies (14(4), 2012), 531-536, and “Flaming? What Flaming? The Pitfalls and Potentials of Researching Online Hostility,” Ethics and Information Technology (17(1), 2015), 65-87.

27Franklin M. Collins, The Relationship between Social Media and Empathy (Dissertation submitted to Georgia Southern University (2014)), available at https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern. edu/etd; see also H.G.M. Vossen & P.M. Valkenburg, “Do Social Media Foster or Curtail Adolescents’ Empathy? A Longitudinal Study,” Computers in Human Behavior (63, 2016), 118-24.

28Ellul (1964).

29 Manuel Becerra, & Anil K. Gupta, “Perceived Trustworthiness within the Organization: The Moderating Impact of Communication Frequency on Trustor and Trustee Effects,” Organization Science (14(1), 2003), 32-44.

30 Francis Fukuyama, Trust the Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (New York: Free Press, 1996), 27.

31 Nancy Baym, Personal Connections in the Digital Age. Digital Media and Society Series (2 nd ed.) (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity Books, 2017).

32 Russ Forrester & Allan Drexler, “A Model for Team-Based Organization Performance.” The Academy of Management Executive (13(3), 1999), 36-49.

33 Margaret Diddams, Lisa Surdyk & Denise Daniels, “Rediscovering Models of Sabbath Keeping: Implications for Psychological Well-being,” Journal of Psychology and Theology (32(1), 2004), 3-11.

About the Authors

Randy Beavers is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Seattle Pacific University. His research interests include executive compensation and financial education. Before joining academia, he worked at the Bureau of Justice Statistics. He holds a Ph.D. in finance from the University of Alabama.

Denise Daniels is a Professor of Management at Seattle Pacific University. Her scholarly interests include the meaning of work, Sabbath, leadership, and motivation. Denise consults and provides executive coaching services in the areas of leadership development, workforce retention, and managing diversity. Denise earned her Ph.D. from the University of Washington

Al Erisman is co-chair of the Theology of Work Project. Previously he was Executive in

Residence at Seattle Pacific University (17 years) and retired from Boeing after 32 years as

Director of Research and Development for Computing and Mathematics. He has authored

numerous books and articles, and is editor and co-founder of Ethix magazine. Al holds a

Ph.D. in applied mathematics from Iowa State University.

Don Lee is an Associate Professor of Management at Seattle Pacific University. His research interest includes strategic alliances, spiritual formation and work engagement, and innovation management. Before joining academia, Don worked at the Korean Institute for International Economic Policy and Nike Korea. He holds a Ph.D. in strategic management from the University of Pittsburgh.