[By Susan Van Weelden and Laurie George Busuttil, 2019]

Abstract

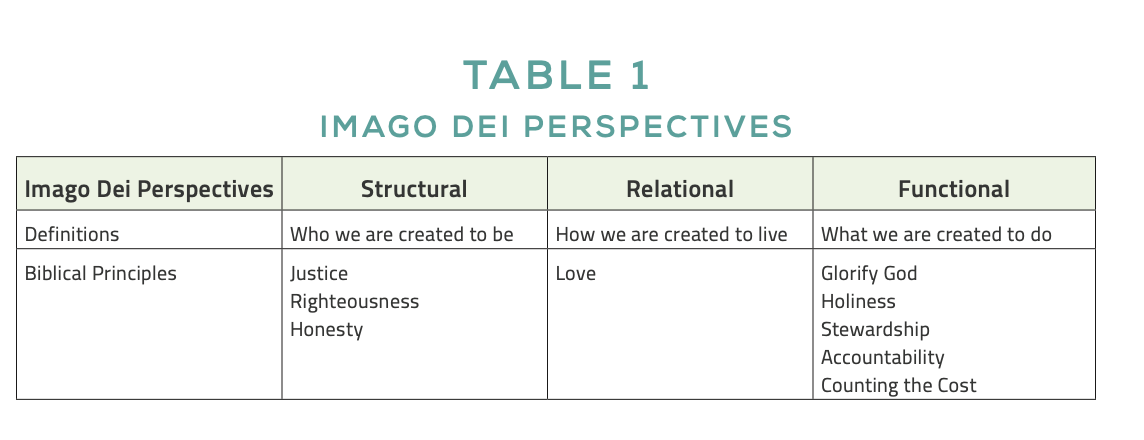

In times of a growing disillusionment with the accounting profession, Christians who are members of that profession desire guidance about how to do accounting with integrity and thereby bring glory to God. Understanding and integrating three perspectives of the imago Dei provide a framework that helps provide this guidance. The structural lens examines who we are created as image bearers of God; the relational lens explores how we are created to live; and the functional lens examines what we are created to do. The integration of these three lenses results in a cohesive understanding of the role of an accountant and impacts the characteristics of the information accountants produce. This perspective also offers a new paradigm for future research and scholarship in the accounting profession.

INTRODUCTION

In turbulent times where business failures and unethical and even fraudulent business and reporting practices abound, there is a growing disillusionment with the accounting profession, whether as members of the management team or as external tax advisors and auditors. Stakeholders of businesses and not-for-profit organizations want assurances that the information accountants provide is trustworthy. Christians who are members of the accounting profession also desire guidance about how to do accounting with integrity and thereby bring glory to God.

This paper develops a framework for how godly women and men can practice accounting in a way that glorifies God. It recognizes that both they and the users of the information they provide are made in the image of God. The framework provides an integrated Christian perspective on the profession of accounting in the following manner. First, the framework integrates three perspectives of the imago Dei, as previously examined by Busuttil & Weelden1 : (a) The structural lens is used to examine who accountants—as image bearers of God—are created to be, (b) the relational lens is used to explore how accountants are created to live, and (c), the functional lens is used to examine what accountants are created to do.

While the next three sections focus on each of these lenses through which we can view accountants as image bearers of God, each section also weaves in aspects of one or both of the other lenses. In the end, a comprehensive understanding of how accountants are impacted by being image bearers of God requires both an aggregation and a blending of the three perspectives.

Second, the framework’s use of the imago Dei provides a single underlying biblical principle that brings coherence to the traditional ways scholars have developed a Christian perspective on accounting. Understanding that we are created as image bearers of God explains why other biblical principles, such as justice, honesty, love, glorifying God, accountability, stewardship, sin, and grace, are important. Third, the framework’s use of the imago Dei is tied to secular accounting theory. By building on a secular framework, we follow Wilkinson’s lead in positioning Christian research within existing research paradigms, thereby ensuring Christian research does not become a series of ad hoc projects.2

IMAGO DEI: THE MEANING OF BEING IN GOD’S IMAGE

The Creation story, as told in the book of Genesis, provides the foundation for our understanding of what it means to be created in God’s image. “So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them” (Gen. 1:27, NRSV). This is reiterated in the next few chapters: “The Lord formed man from the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life” (Gen. 2:7); “When God created humankind, he made them in the likeness of God;” (Gen. 5:1), and “For in his own image God created humankind” (Gen. 9:6).

The Old Testament describes the imago Dei as a process of the Holy Spirit (the breath of life). The New Testament transitions to a Christ-centered focus and suggests that we bear the image of the Son,3 who is himself the image of God,4 and that we live in the hope that “when he is revealed, we will be like him” (1 John 3:2). Christ reflects His Father in several ways, which reveal that He is not just God’s Son but that He is God Himself: He lived a sinless, righteous, and holy life; He performed miracles (raising others and Himself from the dead); and He also called Himself “the first and the last.”5

Attempts by scholars to interpret these passages (particularly Gen. 1 and 2, where the imago Dei was unmarred by man’s fall into sin) and to develop a theology of the imago Dei have given rise to three main schools of thought: structural, relational, and functional (or ambassadorial). These three perspectives provide differing viewpoints about the complexity with which God created humans in His image.

STRUCTURAL PERSPECTIVE

The structural perspective focuses on who we are created to be based on the attributes and characteristics that reflect the image of God. Chewning emphasizes three characteristics: holiness, righteousness, and true knowledge.6 Hill, who says that being ethical is reflecting God’s character, emphasizes three divine characteristics: holiness, justice, and love.7 Wilkinson identifies truth as integrally connected to the persona of God. Christ, who not only bears the image of God but is God,8 describes himself as “the truth.”9 Scripture teaches us that we are to reflect these attributes of God: mercy, faithfulness, goodness, and grace. The Bible also indicates that through the power of the Holy Spirit, we are a new creation.10

RELATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

The relational perspective focuses on how we are created to live in relationship to God and His children—communally-as the Godhead itself communes with one another. We reflect the image and experience of God as we relate to others, seeking to maintain healthy relationships and to build communities that reflect love and respect dignity. “As good stewards of the manifold grace of God, serve one another with whatever gift each of you has received” (1 Peter 4:10). The use of “varied grace”11 in the ESV and “as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms”12 in the NIV emphasizes how people are created with diverse gifts and strengths with which to serve others.

FUNCTIONAL (AMBASSADORIAL) PERSPECTIVE

The functional perspective emphasizes what we are created to do—to glorify God. “So, whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do everything to the glory of God” (1 Cor. 10:31).13 We bring glory to God when we steward the earth’s resources using our diverse gifts. We display God’s image when we serve as the hands and feet of God, caring for this world in a stewardly manner as if the resources of this earth were our own. “We are therefore Christ’s ambassadors, as though God were making his appeal through us” (2 Cor. 5:20). Relying on this verse, Pregitzer encourages believers to “approach the world from the perspective of an ambassador: someone who goes out into the world representing not himself but the King, Jesus Christ.”14

A functional perspective also calls us to holiness, what Hill describes as “the concept of single-minded devotion to God and absolute ethical purity.”15 Single-minded devotion to God draws our focus from individual stakeholders, thus leading us to consider God as our primary stakeholder when making decisions. As a result, absolute ethical purity becomes an outcome of holiness, enabling the godly accountant to provide advice to managers and produce financial statements that fairly and honestly reflect the company’s financial situation.

AN INTEGRATED PERSPECTIVE

Christians agree that humans are created in God’s image and are given life by the very breath of the Holy Spirit, yet the discussion above reveals diverse interpretations of how that image may be actualized. Some authors maintain distinctions among the three perspectives described above; others recognize overlap or combine the perspectives into one overarching description. For example, Hill combines a structural and relational approach when he indicates, “Love’s primary contribution to the holiness-justice-love mix is its emphasis on relationships.”16 Pregitzer says, “We are called to minister to the world as agents of reconciliation between God and Man,”17 revealing how closely related the functional and relational perspectives are.

SIN AND GRACE

Before we proceed to apply the three main interpretations of the imago Dei to the accounting profession, it is crucial to recognize how sin has marred our ability to reflect God’s image and how, in turn, grace restores that ability.

As sinners, our first priority is no longer to glorify God. Instead, we become self-centered. In business, this translates into a distorted view of the purpose of business, where profit maximization takes precedence over providing valued goods and services, creating meaningful employment, and serving the broader community. For accountants, a focus on self translates into producing financial statements that no longer faithfully represent the underlying economic events and instead provide a dishonest measure of a business’s economic achievements. In doing so, accountants may also be covering up attempts to pursue dishonest profit.

The good news for Christians is that Christ’s redemptive grace restores the image of God, for “From his fullness we have all received, grace upon grace” (John 1:16). While sin is still present in this world, Christ’s redeeming grace changes us so that we can mirror God’s justice, righteousness, and truthfulness. Grace enables us to love God and our neighbor. It creates within us a desire to glorify God in all we do, to be holy, and to steward the earth’s resources. As the Apostle Paul urges, “Should we continue in sin in order that grace may abound? By no means! How can we who died to sin go on living in it?” (Rom. 6:1-2)

While dishonest behavior—both sins of omission and sins of commission—may go temporarily or permanently undetected by people, no secrets are hidden from God, who knows our motives and the secrets of our minds and hearts.18 Therefore, Christian accountants are called to be honest in financial reporting even when they have the opportunity and ability to engage in illegal or immoral behavior that might be difficult to detect.

In describing the “relationship between theory and practice,” Wilkinson emphasizes that “while the secular researcher must struggle with relative concepts of truth, as Christian researchers, we have the Scriptures as our basis for truth.”19 This ought to make us bold about calling out behaviors complying with the letter of the law but violating the spirit of the law. It should also lead Christians to make prescriptive statements for accounting about what should be rather than what is.20

THE IMAGO DEI AND ACCOUNTANTS

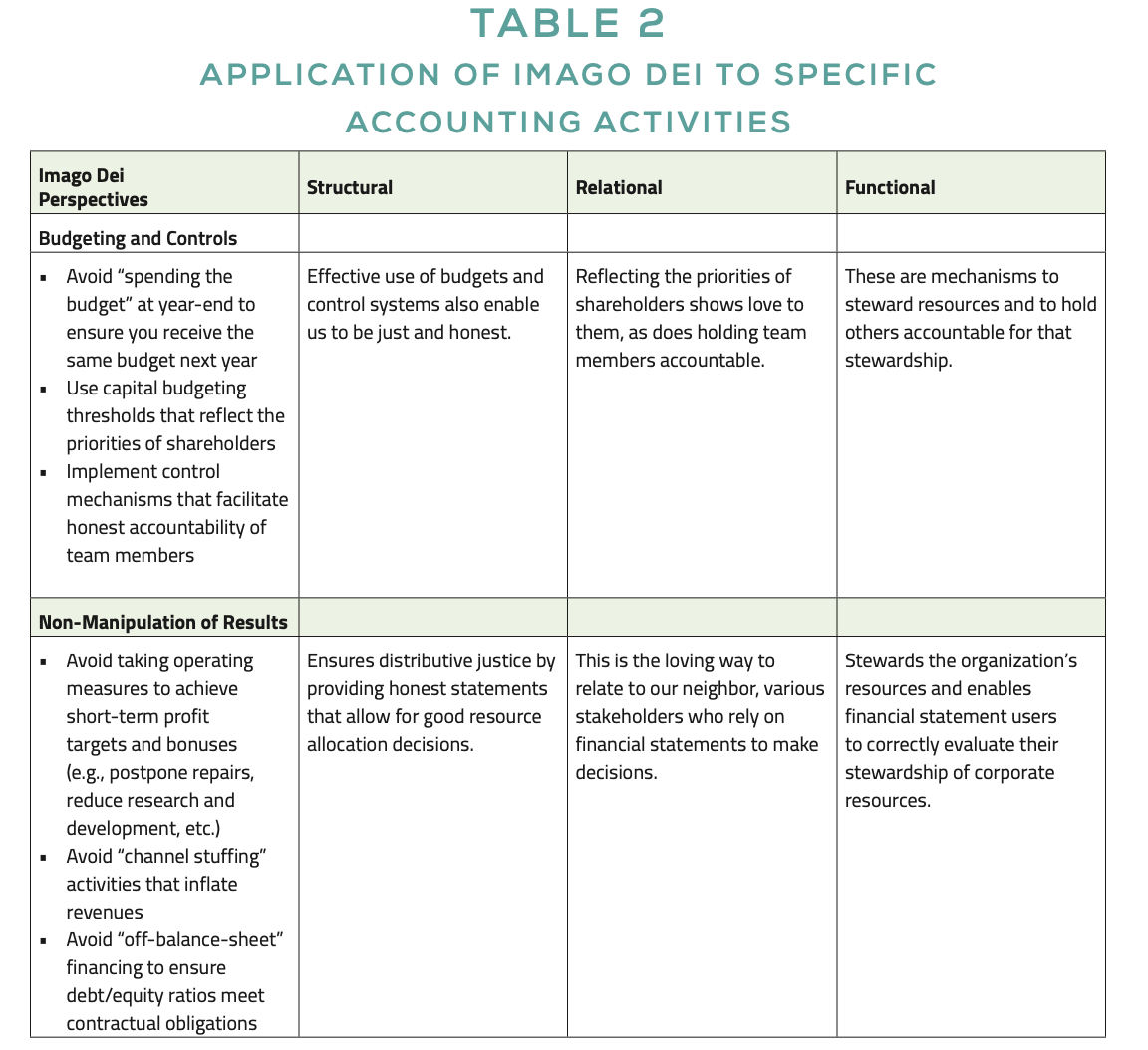

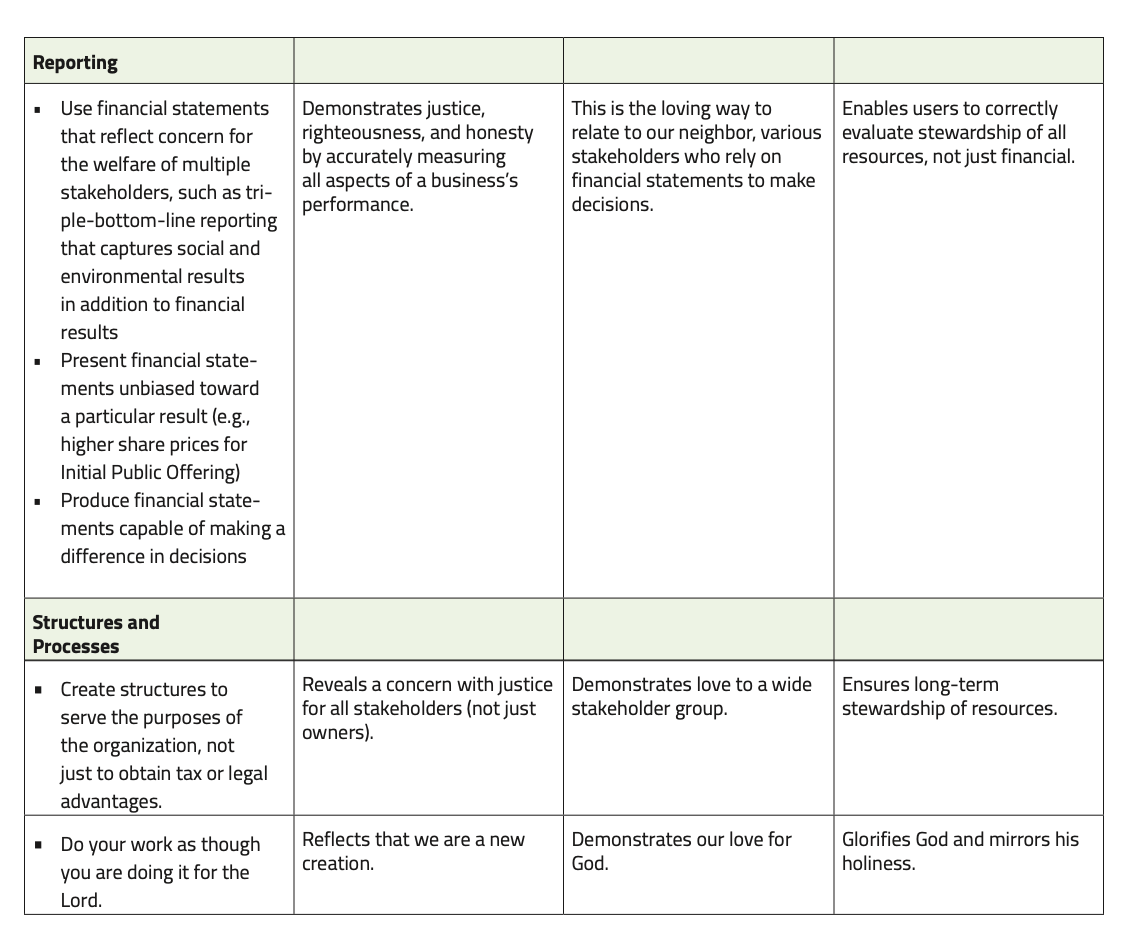

In the remainder of this paper, we apply the three perspectives on imago Dei to create a framework for how accountants can practice their profession in a way that mirrors their Creator and, therefore, brings glory to Him. Table 2 below summarizes the three perspectives and the biblical principles relevant to each.

THE STRUCTURAL LENS: WHO ACCOUNTANTS ARE CREATED TO BE

Under the structural approach, as image bearers of God, accountants bring glory to God when they display His attributes. Three important characteristics of God relevant to the roles fulfilled by accountants are justice, righteousness, and honesty. In turn, the information accountants provide to both external and internal users should itself be just, righteous, and honest.

JUSTICE AND RIGHTEOUSNESS

Scripture emphasizes justice and righteousness as key characteristics of God. “God is not unjust….” (Heb. 6:10), “For in [the gospel] the righteousness of God is revealed through faith for faith” (Rom. 1:17). Hill identifies “God is just” as one of the three divine characteristics that have a direct bearing on being ethical or “reflecting God’s character.”21 Hill distinguishes four basic aspects of justice: procedural rights (fair processes), substantive rights (“what procedural rights seek to protect”), merit (the link between cause and effect), and contractual justice (that we do no harm, respect procedural justice, and fulfill our contractual promises).22 In a similar vein, Boersema describes five aspects of justice: a system of laws or rules, righteousness, fairness/equity, justice in relation to the weak, and distributive justice. Each of these can be applied to the character of godly accountants and to the records they produce.23

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) are guidelines for accounting. They are enforced through such means as the Securities Exchange Commission halting trading of shares when accounting principles are not followed. As will be explored in more detail under the relational lens, God also created people as social beings to live in mutually accountable relationships with others. GAAP and the mechanisms for enforcement are a means of providing mutual accountability between accountants and financial statement users.

A free-market economy relies heavily on ethics (standards of conduct by which actions are judged as right or wrong) and on contract law (which requires people to “make good on” business promises). Accounting relies, in part, on the ethical behavior of managers and accountants to prepare financial statements that fairly present what has transpired in the business. Financial reports also help users evaluate how ethically managers operate their business. For instance, do they repay debts on time, pay employees a fair wage, avoid unnecessary product recalls by spending appropriate amounts on quality, etc. Financial statements play an important role in facilitating contracts between managers (on behalf of businesses) and shareholders, creditors, employees, distributors, suppliers, etc. For example, financial statements that reflect concern for all stakeholders enable the bank to verify the company is not borrowing too much from other sources; help unions to determine what the business can afford in terms of wage increases; and substantiate sales upon which royalties are due, etc. Table 2 illustrates how such financial statements are also consistent with the relational and functional perspectives of the imago Dei.

Biblical requirements to use “honest balances, honest weights”24 —or accurate measures of the success of a business—are part of righteousness. As image bearers who value living uprightly before a Holy God, accountants recognize success cannot be measured purely in financial terms. Thus, triple-bottom-line reporting 25 (see Table 2) provides well-rounded information about an organization’s treatment of its employees, service to customers, partnerships with suppliers and dealers, environmental sustainability, and community service. Biblical attributes of fairness or impartiality must be mirrored by accountants so they do not prepare financial statements and other information biased toward a particular stakeholder group (e.g., creditors) or result (e.g., obtaining a bank loan) (see Table 2). As image bearers of a just God, accountants also serve the interests of stakeholders who are “weak” compared to managers, in that they do not have the inside information managers possess but must rely on accountants and managers to deal with them justly when it comes to providing information.

Finally, accounting information is used to make resource allocation decisions that achieve distributive justice. For instance, managers decide whether or not to pay dividends to shareholders or to reinvest profit into the business. They also decide how much they can afford to pay employees or to spend on environmental sustainability and social responsibility. Shareholders decide which businesses to invest in, and if accounting records accurately measure the performance of businesses (especially profitability), the best-performing businesses will attract more investment, leading to the fair allocation of resources. This means that manipulation of results such as channel stuffing to inflate revenues or off-balance-sheet financing to meet debt covenants are not choices Christian accountants can make. Employees may decide to leave or seek employment in the organization based on the narrative presented in financial statements. In providing information that enables others to make resource allocation decisions, accountants must also apply the principle of love, which leads us to the relational lens.

HONESTY

The Bible also depicts honesty, or truthfulness, as part of God’s character. “In the hope of eternal life that God, who never lies, promised before the ages began…” (Titus 1:2) and, “Whoever has accepted his testimony has certified this, that God is true” (John 3:33). When God in the ninth commandment says, “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor” (Exodus 20:16), He teaches us to “avoid lying and deceit of every kind” and to “love the truth, speak it candidly, and openly acknowledge it.”26 “Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth” (1 Cor. 13:6), or “So then, putting away falsehood, let all of us speak truthfully to our neighbors” (Eph. 4:25). These general requirements for honesty extend, of course, to the accounting profession.

Wilkinson focuses on truth, as found in the person of God and as revealed in His Word. His framework for a Christian perspective on accounting is an extension of a secular framework by Chua that identifies different paradigms for accounting research based on their underlying worldviews.27

Honesty is an everyday word for the accounting term of representational faithfulness, one of two fundamental qualitative characteristics of useful financial statements according to the Conceptual Framework adopted by the Financial Accounting Standards Board in the United States, the Accounting Standards Board in Canada, and the International Accounting Standards Board. (The other is relevance, which will be discussed under the relational lens.) “Financial reports represent economic phenomena in words and numbers. To be useful, financial information … must also faithfully represent the phenomena that it purports to represent. To be a perfectly faithful representation, a depiction would have three characteristics. It must be complete, neutral, and free from error.”28 Representational faithfulness requires that there be no manipulation of profit (upward to impress shareholders or downward to escape the attention of regulators) or misstatement of assets and liabilities, either through adjustments to the financial statements or adjustments to operations (such as postponing research and development). See Table 2 for examples of how the other lenses also apply.

THE RELATIONAL LENS: HOW ACCOUNTANTS SHOULD LIVE

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And a second is like it: you shall love your neighbor as yourself” (Matt. 22:37-39). These great commandments—the New Testament summary of the Ten Commandments—reflect, first and foremost, that, as image bearers of a triune God, accountants are created to be relational beings, bringing glory to God as we live in relationship with God and other people.

With respect to our relationship to God in the workplace, accountants, too, are admonished, “Whatever your task, put yourselves into it, as done for the Lord and not for your masters” (Col. 3:23) (See Table 2). In other words, we are called to live out the first commandment in how we go about our daily work.

Accountants must work to provide financial statements and other information that is concerned with the welfare of our neighbor. In the Parable of the Good Samaritan, Christ defines our neighbor in very broad terms—even to the point of including our enemy.29 In business, our neighbor includes all relevant stakeholders impacted directly or indirectly by the actions and reports of a business or not-for-profit organization, including shareholders, creditors, employees, managers, government authorities, and the wider community. Thus, there is a biblical requirement for accountants to produce financial statements and reports for management that “do unto others,” by providing others with information we ourselves would like to have.

Hill suggests “self-love is healthy, reflecting our status as image bearers.” Self-love has a ceiling that prevents us from thinking only of ourselves and a floor that prevents us from thinking nothing of ourselves.30 White is more mindful of the first danger, a selfish leadership style that produces financial reports serving self-interests instead of a servant leadership style that looks out for the interests of others.31

Showing love to financial statement users is also consistent with the professional requirement to produce relevant information (see Table 2). The Conceptual Framework identifies relevance as the first fundamental qualitative characteristic of financial information. “Relevant financial information is capable of making a difference in the decisions made by users.”32 As such, it can have “predictive value”—whereby it provides users with the information they need to make their own predictions.33 It can have confirmatory value, in that it enables users to confirm or change previous evaluations.34 Relevant information also contains all material information. “Information is material if omitting it or misstating it could influence decisions that users make;” it encapsulates both the nature and magnitude of an amount. 35

The requirement to mirror God’s love should be the primary motivation for accountants as we capture events and transactions in monetary terms so the organization’s success can be evaluated (scorecard); motivate behavior toward the organization’s goals (control); and monitor the behaviors of managers (watchdog). Showing love in performing these functions relates directly to being honest and just. The ability to show love—despite the impact of sin in our world—by putting the needs of others first arises because Christian accountants are restored by the redeeming grace of Christ in the image of a loving God, thus enabling them to mirror God’s love.

THE FUNCTIONAL LENS: WHAT ACCOUNTANTS ARE CREATED TO DO

Lastly, as people made in the image of God, accountants bring glory to God as we steward the earth and its resources. In essence, we are God’s agents; we are ultimately accountable to God for our stewardship of His resources. As stewards, we are entrusted with resources committed to us by God—an abundance of physical or earthly resources, as well as individual creative, mechanical, and intellectual talents. In a business setting, as accountants contribute to the effective and efficient use of resources, we are able to create wealth for the owners of those resources, as Jesus described in Luke 19:11-27. Creating wealth, helping a business to grow and expand, reflects God’s creative nature of Genesis 1 and 2 and follows Jesus’s teachings. As we use our creativity and intellect, we can develop innovative products and processes (including accounting processes), such that our world is ever evolving, thereby fulfilling the creation mandate to “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over…every living thing that moves upon the earth” (Gen. 1:28). In response to God’s command to His image bearers to have dominion over the rest of creation, we are, in a sense, co-creators with God.

The Bible indicates that we will give an account of our actions before God. “So then, each of us will be accountable to God” (Rom. 14:12). God “is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart … before him … all are naked and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must render an account” (Heb. 4:12-13).36 Harrison emphasizes we are accountable to the Creator and to other people, relating this to the social nature of God and of man: stewardship deals with “the discharging of agency activities on behalf of a principal—an operating activity—whereas accountability deals with reporting the results to the principal—an accounting activity.”37 The principles of stewardship and accountability within an agency setting are biblical concepts, discussed in the Parables of the Tenants, Talents, and Shrewd Manager.38 In each case, resources, or talents, are to be stewarded by agents (tenants, slaves, manager) for the purpose of growing those resources. In each case, the stewards are required to give an account of their management of the owner’s wealth.

Accountants assist managers with performing their duty of accountability. Accountants also serve as watchdogs, holding managers responsible for whether they are faithful in their duties of stewardship and accountability. Thus, stewardship and accountability relate directly to the main purpose of accounting. The Conceptual Framework states, “The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders, and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity.”39 The Conceptual Framework goes on to say that in order to assess an entity’s future net cash inflows (important for the ability to pay interest and dividends, and to repay debt), existing and potential investors and lenders need information about “the resources of an entity, claims against the entity, and how efficiently and effectively the entity’s management and governing board have discharged their responsibilities to use the entity’s resources.”40

White suggests that “since we are held accountable by God to be good stewards of his creation, we need to develop accounting systems that give an observable and reportable form to a much broader spectrum of business activities than currently exists.”41 She discusses two particular examples, accounting for human resources and accounting for environmental costs, not traditionally captured in the accounts—although some organizations now practice triple bottom line reporting that includes some of these measures.

Harrison points out that “because of man’s social nature, we must be accountable to other people in order to interact with them.” Then, to ensure we do not exploit others, mutual accountability forms the basis for contracting.42 Accountants also provide internal control mechanisms to ensure an organization can successfully achieve its goals (see Table 2). For example, internal controls include assignment of responsibility, segregation of duties, documentation, physical controls, review and reconciliation, budget reviews, expenditure approvals (to prevent, for example spending the budget at year-end to ensure that budget allocations are not cut next year), and codes of conduct.

In this respect, accountants recognize we also live in relationship to others. We are called to hold each other to high standards by strengthening each other “as iron sharpens iron” (Prov. 27:17) and to work together, “because [we] have a good reward for [our] toil. For if [we] fall, one will lift up the other” (Eccl. 4:9-10). Bonhoeffer argues that recognizing God’s image in another results in human freedom, “being-free-for-the-other,” and understanding “life as responsible vis-a-vis the other human being.”43

Chewning, et al., suggest this freedom is bounded by structure and limits, thus channeling the efforts of individuals to work together toward a common goal. The control mechanisms adopted within such bounded freedom must be freely chosen by the individuals who are responsible for each other because they will see the benefit in adhering to the requirements.44 Accountants, therefore, should hold each other and managers accountable to the high standards of the Conceptual Framework and to ethical behavior, ever sharpening each other’s knowledge and abilities and holding each other to the standards that bound the freedom of accounting decisions.

The biblical principle of counting the cost is also related to stewardship. Boersema contends counting the cost is so important it deserves separate consideration. “Because of scarcity, largely caused by sin, economics is very much a matter of making choices—of allocating scarce resources.”45 This is a question of analyzing costs and benefits, including those that cannot be readily quantified. “Good stewardship requires the use of all our talents to come to a responsible use of the available resources.”46 The last statement suggests that counting the cost also reflects our intellect and creativity, thus also reflecting characteristics of God that we, as His image bearers, inherit. God provided the ultimate example of counting the cost, knowing full well the anguish He would experience when He sent His Son to die for the forgiveness of our sin and the redemption of the universe.

INTEGRATING THE THREE LENS

Although we have discussed the three perspectives separately in previous sections, Table 2 shows that practicing accounting in a way that truly and fully reflects what it means to be image bearers of God requires an integration of the three perspectives. The table provides an illustration of how the three imago Dei perspectives can be applied to specific accounting activities. It uses examples discussed in the preceding text and introduces other examples as well.

CONCLUSION

Accountants—like all people—are image bearers of God. Various stakeholders who use the information accountants provide are also image bearers of God. This should have a profound impact on how we, as accountants, understand our role and on the characteristics of the information we produce. Viewing the imago Dei from an integrated lens means we can begin to glimpse who accountants are (structural lens), how we should relate to others (relational lens), and what we do (functional lens) in terms of how God ordains accounting to be practiced. As accountants, we do our work in a way that brings honor to our creator when we are just, honest, and righteous; show love to God by showing love to others; and recognize our role as one consecrated by God to enhance stewardship and accountability for His glory.

NOTES

1 Laurie George Busuttil and Susan Van Weelden, “Imago Dei and Human Resource Management: How Our Understanding of the Breath of God’s Spirit Shapes the Way We Manage People,” The Journal of Biblical Integration in Business (21(1), Fall 2018). This article provides an in-depth description of the three perspectives and their theological roots.

2 Brett R. Wilkinson, “A Framework for a Christian Perspective on Accounting Research” in The Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, Fall 2005, 62.

3 See 1 Cor 15:47-49; Col 3:10-11; Rom 8:29.

4 See 2 Cor 4:4; Col 1:15.

5 Rev 1:17, 22:13.

6 Richard C. Chewning (Ed.), Biblical Principles and Business: The Foundations, Volume 1. (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 1989), 134. See Eph 4:23-24 and Col 3:10.

7Alec Hill, “Just Business: Christian Ethics for the Marketplace,”

3rd Edition (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press), 7.

8 “Wilkinson, “Framework,” 62.

9 John 14:6.

10 2 Cor 5:17.

11 1 Pet 4:10, English Standard Version

12 1 Pet 4:10, New International Version

13 Col 3:23 also admonishes us, “Whatever your task, put yourselves into it, as done for the Lord and not for your masters.”

14 Michael Pregitzer, “Introducing the Ambassador Scorecard: A Christian Approach to HR Professional Excellence” in Christian Business Academy Review (Vol. 3, 2008) 49.

15 Hill, Just Business, 18.

16 Ibid. 54.

17 Pregitzer, “Ambassador Scorecard,” 49.

18 See 1 Chronicles 28:9, Psalm 7:9 and 44:21, Proverbs 16:2, 1 Samuel 16:7, Romans 8:27, 1 Corinthians 4:5, and 1 Thessalonians 2:4.

19 Wilkinson, “Framework,” 68-69.

20 Ibid, 65-66.

21 Hill, Just Business, 7.

22 Ibid, 37-41.

23 John Boersema, Political-Economic Activity to the Honour of God (Winnipeg, MB: Premier Publishing, 1999), 50-55.

24 Lev 19:35-36

25 “The triple bottom line (TBL) is a framework or theory that recommends that companies commit to focus on social and environmental concerns just as they do on profits. The TBL posits that instead of one bottom line, there should be three: profit, people, and the planet.” https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/triple-bottom-line.asp, accessed July 9, 2019.

26 “The Heidelberg Catechism, Lord’s Day 43,” Our Faith: Ecumenical Creeds, Reformed Confessions, and Other Resources, (Grand Rapids: Faith Alive, 2013), 110.

27 Wilkinson, “Framework,” 62-64.

28 CPA Canada Handbook – Accounting, Part I – IFRS Standards, 2019 Edition, QC12; FASB Statement of Financial Concepts No. 8, As Amended August 2018, Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting, QC12.

29 Luke 10.

30 Hill, Just Business, 63-64.

31 White, 9.

32 Conceptual Framework, QC6.

33 Ibid, QC7.

34 Ibid, QC9.

35 Ibid., QC11.

36 See also Ezek. 18:20 and Mat 12:36.

37 Walter T. Harrison, Jr., “Biblical Principles Applied to Accounting,” in Biblical Principles and Business: The Practice, ed. Richard C. Chewning, 107-120 (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 1990), 113.

38 See Matt 21:33-46; Matt 25:14-30; and Luke 16:1-15.

39 Conceptual Framework, OB2.

40 Ibid, OB4

41 White, “Christian Perspective,” 13.

42 Harrison, Jr., “Biblical Principles,” 111.

43 Clifford J. Green, Bonhoeffer: A Theology of Sociality. (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 294.

44 Richard C. Chewning (Ed.), Biblical Principles and Business: The Practice, Volume 3. (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 1990), 160.

45 Boersema, Political-Economic Activity, 60.

46 Ibid, 60.

About the Authors

Susan Jean Van Weelden is Professor of Business and Dean of Social Sciences and Co-Dean of Humanities at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario, Canada. She has taught at Redeemer’s Business Program for over thirty years, and her teaching load includes courses in accounting, organizational behavior, leadership, and strategy. Susan is a CPA, CMA, with an MBA from McMaster University.

Susan Jean Van Weelden is Professor of Business and Dean of Social Sciences and Co-Dean of Humanities at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario, Canada. She has taught at Redeemer’s Business Program for over thirty years, and her teaching load includes courses in accounting, organizational behavior, leadership, and strategy. Susan is a CPA, CMA, with an MBA from McMaster University.

Laurie George Busuttil is Associate Professor and Chair of Business at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario, Canada. She teaches in the management, marketing, and not-for-profit management streams. She holds an MBA from McMaster University and an MTS from McMaster Divinity College.

Laurie George Busuttil is Associate Professor and Chair of Business at Redeemer University College in Ancaster, Ontario, Canada. She teaches in the management, marketing, and not-for-profit management streams. She holds an MBA from McMaster University and an MTS from McMaster Divinity College.