[By: Will Oliver, 2020]

ABSTRACT

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reflects a new theory of business today, in which businesses work for more than just profit; they strive to improve people and planet as well. Christian business leaders have the strongest reason for treating people and the planet well. They run their businesses to praise God, who clearly loves treating people well and preserving his planet. This article explores how Christian business leaders can lead their companies differently than other well-meaning companies engaged in CSR. It offers a practical framework through which Christian business leaders can improve how they offer their businesses as praise to God. The article explores three questions: what is the shift in business theory underlying the Triple Bottom Line (TBL); in what ways can a Christian business leader praise God as a matter of business objective; and in what ways could praise be measured as a separate bottom line? It concludes with some practical suggestions on the implementation of this new dimension of corporate responsibility. .

INTRODUCTION

Profit has long been business’ definition of success. In 1962, Milton Friedman reflected a common view: “there is one and only one social responsibility of business: to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits.”1 With Shareholder or Agency Theory, the leader is considered an agent of company shareholders with the primary responsibility of increasing shareholder wealth.2 Then, in 1994 John Elkington coined the phrase “Triple Bottom Line” (TBL), proposing that companies pursuing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) need to manage Profit, People and Planet, together.3 Now, over 92% of the world’s 250 largest companies publish an annual CSR report.4 They find that the three “Ps” interact. Profit provides the economic sustainability necessary to maintain people and planet.5 People do the work of the company, buy its product and provide for the general community supporting the business. In turn businesses assure quality of life: respect for human rights and equality, cultural identity/diversity, race and religion. People as well as the business itself depend on the planet. In the long run maintaining the quality of the environment is necessary for healthy people and profit from economic activities.

This paper begins with a review of TBL. Next, it introduces “Praise” as a fourth bottom line. An examination of current approaches to measuring “People” and “Plant” as business objectives is then followed by an explanation of how and why “Praise” could be measured as a bottom line, supported by a few examples of Quadruple Bottom Line businesses. It ends with a challenge to further research on implementing “Praise” as a measurable business objective for Christian leaders.

EVOLVING THEORIES OF BUSINESS

Garriga and Domènec classified the main business theories underlying CSR into four groups: (1) instrumental theories, in which the corporation is seen as only an instrument for wealth creation, and its social activities are only a means to achieve economic results; (2) political theories, which consider the power of corporations in society and a responsible use of this power in the political arena; (3) integrative theories, in which the corporation is focused on the satisfaction of social demands; and (4) ethical theories, based on ethical responsibilities of corporations to society.6

Pride suggests four typical arguments for increased social responsibility: (1) business is part of society and it cannot ignore social issues; (2) business has the technical, financial, and managerial resources needed to tackle today’s complex social issues; (3) business can create a more stable environment by helping resolve social issues; and (4) business can reduce government intervention by using socially responsible decision making.7

Three primary theories seem to be at the root of the change: Human Resource, Stakeholder and Common Goods.8 Human Resource Theory is a departure from the 19th century Scientific Management theory of how businesses manage people. From Adam Smith through Frederick W. Taylor,9 Scientific Management held that the role of the business leader was to manage worker performance to increase profit. Scientific Management studied the profit impact of changes to pay structures, organizations and work design. Then, a new crop of business writers changed the discussion during the middle of the 20th century. Human Resource Theory reflects that people are not merely resources for profit-making. It is built on the organizational behavior perspective, where Maslow theorized that individuals each have different types of needs.10 McGregor added that individuals need good direction to help them serve the company.11 Ouchi observed from Japanese management styles that make employees feel they are part of a supportive environment.12 Boyatzis found that business leadership achieves the best result by helping employees align personal self-image with the company mission.13 The ascendance of Human Resource Theory has led to the second dimension of business success: “People,” in addition to “Profit.”

Stakeholder Theory also helps explain CSR, which is grounded in the notion that business leaders owe a broader allegiance to the community beyond its employees.14 Brown links CSR to Adam Smith’s 18th Century writings and concludes that companies have both a duty and an opportunity to help the broader community.15 Charles Handy described businesses as living communities of individuals, so that “the essential task of leadership is to combine the aspirations and needs of the individuals with the purposes of the larger community to which they all belong.”16 Under Stakeholder Theory, businesses should create jobs to benefit those who otherwise would be left behind. Stakeholder responsibility means businesses have “neighbors” much like the Good Samaritan.

The concern for the “Planet” is built upon the Common Goods Theory (Theory of Externalities or Theory of the Commons).17 It recognizes that some activities generate short term profit for one business at the expense of other businesses and people (present and future generations).18 Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, the first Earth Day in 1968, the Environmental Protection Act of 1970 and numerous court cases and legislative actions all reflect changing attitudes about responsibility for the planet we share. For many, environmentalism is largely pragmatic in nature. It holds that the acts of one company should not be allowed to adversely affect others, not, at least, without paying a price. It also holds that businesses’ responsibility extends not merely to our neighbors today, but also to future generations. Patagonia is famously passionate about selling products which promote a better planet. Founder Yvon Chouinard built his company to protect the planet. Oliver Falck suggests that, “by strategically practicing corporate social responsibility, a company can do well by doing good.”19

PRAISE AS A BUSINESS RESPONSIBILITY

God does not want to be a shareholder or stakeholder in any business. He is not interested in a Balanced Score-card. God wants our praise to be the primal, organizing goal of every business, enveloping all bottom-line endeavors. He wants Christian business leaders to thank and praise him as the provider of all the resources including employees, customers, investment capital, patent ideas, …everything. The psalmist declares, “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it, the world, and all who live in it” (Ps. 24:1, NIV). The Christian business leader honors God’s planet as a matter of celebrating and honoring the Giver. Paul describes in Ephesians 3 a process of revelation, grace, power of the Holy Spirit, becoming a servant, grasping the love of Christ, being filled with God’s fullness, then giving glory to Him. Again, in 2 Cor. 5 Paul explains the Christian [business leader] has been reconciled to God, and in the process re-created into God’s ambassadors and co-workers. James explains that the new creation exhibits a “wisdom that comes from heaven [and] is first of all pure; then peace-loving, considerate, submissive, full of mercy and good fruit, impartial and sincere” (James 3:17). The Christian business leader treats other people well, not out of duty, but out of his/her regenerated nature. The Christian manager conducts business not as a matter of profit or law, or to receive a reward, rather because it is in the nature of God’s new creation. The Christian business leader has an opportunity to pursue a fourth bottom line: “Praise.”

Three questions help unpack praise as a business objective: what is praise; is it meaningful to measure, and how could it be measured? The Psalms are often turned to as a source for understanding praise. The psalmist exclaims, “You are my God, and I will Praise You” (Ps. 118:28). The Hebrew word for “praise” here is yadah, which means give thanks or confess.20 Words used in the Bible as synonyms or in parallel with praise include: bless, exalt, extol, glorify, magnify, thank and confess. To praise God is to call attention to his glory, and “Praising God is a God-appointed calling. Indeed, God has formed for himself a people ‘that they may proclaim my [God’s] praise.’”21 C.S. Lewis confesses that he initially misread the many expressions of praise in the Psalms to read that “God has the ‘right’ to be praised.”22 Eventually, Lewis came to realize instead that, praise and “admiration is the correct, adequate, appropriate, response to” a wonderful God.

Reflecting his regenerated nature, the Christian business leader instinctively wants to praise God for being God. He wants to acknowledge God’s generous gifts of a business, people working in it and wonderful environmental resources being used.

In the words of the Westminster Shorter Catechism, the Christian business leader’s chief purpose in managing is “to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.”23 More than thanking God quietly in the closet, Lewis suggests that the Christian business leader wants to share God’s praise. This is much in the same sense as one would spontaneously praise anything of high value, and also instinctively urge others to join in the praise. In praise we are rhetorically asking, “Isn’t she lovely? Wasn’t it glorious? Don’t you think that is magnificent?”24

WHAT IS PRAISE?

God is honored through the Christian business leaders’ public praise: “I will Praise you, Lord, among the nations” (Psalm 57:9). Theologians would argue that “While privately spoken praise to God is fitting and right, it is virtually intrinsic to the notion of praise that it be publicly expressed.”25 Nothing in the Bible suggests praise should be limited to songs or a worship service. R. C. Sproul suggests that praise and thanksgiving should permeate the Christian business leader’s life.26 The psalmist declares: “Let everything that has breath praise the Lord” (Ps. 150:6). Jesus says too if [Christian business leaders] “keep quiet, the stones will cry out [in praise]” (Lk. 19:40). We can praise God through the spoken word, published books, newspaper articles, Facebook posts, or blogs. Today more than ever, we have many opportunities to express God’s greatness.

IS IT MEANINGFUL TO MEASURE PRAISE?

Although Christian business leaders need to be “beware of practicing your righteousness before other people in order to be seen by them” (Mt. 6:1), the impact of a praiseful business is a way of keeping it focused on pointing others to God. The Billy Graham ministry reports praiseworthy metrics: 2.2 billion people heard him preach, 215 million attended his live events, 2.2 million responded to the invitation to become a Christian while at one of his crusades, and so on.27These are reported so that they can thank and praise God for allowing them to be part of advancing His Kingdom. A Google search on “Marion E. Wade” (ServiceMaster founder), produces 9.6 million hits.28 Leafing through first five pages of the hits reveals that nearly all were references to ways he glorified God through and as a result of his successful company. Publishing these metrics brings praise to God. Marion E. Wade wrote,

The head of any corporation big or small has the responsibility of conducting his business along lines that will keep his employees working and keep his stockholders happy. But this is not his first responsibility. His first responsibility is to conduct his business along lines that will be pleasing to the Lord. And he must do so not because of any rewards he hopes to receive but because, for a Christian, there is no other way.29

The Christian business which earns a profit, builds people up and helps to sustain the planet is doing a praiseful thing. Yet, “Praise” is more than just achieving a great TBL. Non-Christians achieve those as well. For example, Patagonia’s mission is to “use business to protect nature.”30 Ben & Jerry’s has a mission of giving back to the community, and so on. The worldly CSR company does good for the world’s sake. The Christian business leader credits God as the source, inspiration and power behind the business results.

MEASURING THE QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE

Accountants have always faced the challenge of balancing the need for relevant information against the requirement for accurate numbers.31That challenge increases with TBL companies. Academic researchers such as Slapper have pondered how, and even if people or planet performance can be reduced to numbers. Slapper acknowledges, “There is no universal standard method for calculating TBL.”32 In spite of such challenge, useful metrics have and can be developed to offer meaningful measurement of the TBL. Some of these examples are discussed in the side box: Measuring TBL.

Given the challenge for measuring TBL, is there a practical way for the Christian leader to measure “Praise” as a fourth bottom line? Two important considerations in measuring praise include observing behaviors that honor God, and observing the level at which that behavior is attributable to the working of the Spirit. When we are reborn as a new person in Christ, we naturally exhibit the fruits of the Spirit. Erisman and Daniels showed how love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control may be exhibited in employees’ behavior.40 They used a closed coding approach to identify terms representing fruits of the Spirit in the performance appraisal forms employed by sixteen secular organizations. They found terms representing the fruits in each of the companies’ performance evaluation tools. The results suggest the possibility of measuring behavior at the corporate level—looking for fruits of the Spirit in many company documents. Outside the scope of that study was whether a company (individual) that acknowledges God performs differently. Hopefully, a company led by a Christian business leader would evidence more instances of fruits of the Spirit (a form of praise to God), and would acknowledge God’s hand in its business.

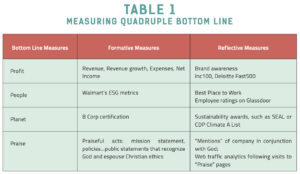

Potential performance measures can be formative or reflective. We are most familiar with formative measures: sales produces profits, low wages induce employee turnover, toxic waste discharge causes fish to die. Table 1 summarizes some representative ways companies report formative measures of Profit, People and Planet. Formative measures report things businesses do to promote TBL. Christian business leaders can also measure the things they do to praise God. Table 1 proposes some things companies can do to deliberately praise God. Dave Kahle proposes, “If we want to impact generations of people, we need to make a commitment to a cause larger than ourselves (serving the Lord) and publicly declare that commitment…like a stone thrown into a pool of water, the ripples of impact can spread beyond our ability to discern. It may even be the tipping point to transform a community.”41

Chick-fil-A could count the ways they make public statements for God. For example, when they stay closed on Sun- days, host a flash dance with a church group, play Christian music in their stores, they offer acts intended to praise God in and through their business. H-E-B groceries was founded by Howard E. Butts, a Christian businessman, and 115 years later still gives 5% of its profits to charity.42 Hobby Lobby’s founder David Green openly and unapologetically leads his company based on his Christian commitment. The Hobby Lobby mission statement talks about its Christian principles, and clearly intends to align all stakeholders with biblical principles.43 Through these acts, businesses offer praise to God. These do not “add up” in the way sales or expenses do, but can be tallied and reported—as acts of praise. The purpose is not some expression of sum, but the act of being deliberate about praise.

Measures of “Praise” can also be reflective. When Chris- tian business leaders acknowledge God publicly, the world responds—sometimes positively, sometimes negatively. Either way, the resulting recognition is “reflective” of the impact the business’ acts of praise is having. Table 1 speculates as to the types of reflective “Praise” measures Christian business leaders could monitor. When journalists write about the faith of Marion E. Wade or S. Truett Cathy, they reflect those Christian business leaders’ lives of praise. Tallying that reflective measure of “Praise” can help the business stay focused on achieving “Praise” as a bottom line.

Two examples of measurement of a company’s “Praise” effort are tracking public mentions and monitoring traffic patterns on the company’s web site. Public mentions happen whenever someone name-drops a company, its employees, business decisions, products or brands names. Mentions can be in any instance in the media (press, social media, job posting sites, etc.) Using social listening tools such as Google Alerts, a Christian business leader could employ social listening to identify which praise messages are being noticed, when, how frequently and by whom. Measures could track the positive or negative nature of each mention. Even a negative opinion about praise activity acknowledges God. Awareness of how the world responds to praise messages helps the Christian business leader know if its message is “getting through”—the extent to which God is being praised through the company’s activities. It can also help refine the company’s praise messages for best effect.

Monitoring traffic on the company’s own website (and Facebook, Twitter, etc.) is another approach. Major web sites commonly monitor users’ web footprint employing web tracking tools such as Google Analytics. They use cookies to track who visits which pages and what they do on the site afterward. AI-based tools watch shoppers’ web footprints, compare them to the activity of others with similar footprints, and make judgment about potential future interests. Using such tools, Christian business leaders could track the effect praise messages have on user activity. How many views do statements of praise get? If viewers see a page suggesting that the company is not open on Sunday in honor of God, do the praise message influence users’ behavior? Christian businesses glorify God when they tell others about how they live for God’s glory.

EXAMPLES OF QUADRUPLE BOTTOM LINE COMPANIES

Christian business leaders have an opportunity to build businesses based on a different way of thinking about the role of business in the world. They have the responsibility to deliver profit and good for people and planet, as part of offering praises to God.

Eventide Investments manages mutual funds dedicated to “investing that makes the world rejoice.” Their tagline comes from Proverbs 11:10, “When the righteous prospers, the city rejoices.” Biblically, when righteous individuals (and by extension, their businesses) prosper, the neighbors and city of the righteous are supposed to rejoice. Eventide evaluates how a business is adding value to various stakeholders: customers, employees, vendors, host communities, the environment, and the broader society. Eventide’s goal is to invest in businesses that add value to its neighbors, rather than degrading them.44

Dedicated to investing for profit and God’s glory, IBEC Ventures publicly asserts its mission is to build sustainable businesses that change lives and transform communities. With business viewed as a mission, the goal is to reconcile and integrate three bottom lines all at the same time. In making business judgments, it asks: what is good for profit; what is good for all stakeholders including employees; and what is good for God’s kingdom? This requires deliberate management choices. IBEC suggests a fourfold purpose: (1) creating sustainable profit and wealth in the communities where they operate, (2) providing jobs that give employees both income and dignity, (3) pursuing spiritual capital and making followers of Christ, and (4) promoting stewardship of God’s creation.45

The Impact Foundation’s mission is to seek “better ways to accomplish good in the world.” Over the past several years, they have placed more than $54 million in over 100 what they call Impact Companies. This fund’s view is that “God doesn’t need our money, but in His kindness, He allows us to participate in His work in the world.”46 Impact Foundation invests in companies so the Kingdom of God may advance, the lost are found, the hungry are fed, the orphan housed, and justice is carried out. Christians are called to invest in business in order to accomplish good in the world, for His glory.

Partners Worldwide sees business as a holy calling. They work to put work and worship back together. One example of Partners Worldwide’s Kingdom business is Pueblos en Accion Comunitario (PAC), which works to end food insecurity and poverty in rural areas of Nicaragua. PAC empowers rural farmers by advocating for them, equipping them with training and loans, and providing access to larger markets. It has allowed 750 local coffee farms to achieve better profit, stronger focus on people, more sustainable farming practices…and glory to God. Partners Worldwide tracks its global impact, which in 2017-18 included over 200,000 jobs in 32 countries through 147,000 business/farms and $16.7 million in loans, all these to sustain a vision “to end poverty so that all may have life and have it abundantly.”47

CONCLUSION

Profit, People, Planet and Praise: four crucially important outcomes God wants all Christian businesses to achieve. Christian business leaders can serve as “a nation of priests” in the world. They would work diligently to praise Him through the profit they earn and from doing good for people and plan- et. Delivering bottom line profit, people, planet and praise re- quires new forms of management. These include new kinds of mission, new ways of looking at customers, new types of investment, and new ways of planning, managing and measuring the way businesses praise God. TBL measures are being actively pursued by academics and business leaders, but the Christian business leader has the unique opportunity to explore and experiment with a new way of measuring the fourth bottom line, “Praise.” The concept of a Quadruple Bottom Line will offer Christians a powerful opportunity to use business to drive a Jesus Revolution across the global marketplace.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

WILL OLIVER is Professor of Business and head of the business faculty at Sattler College in Boston, MA. As an entrepreneur he has started four companies and is a partner in a private equity firm. His consulting experience spanned global brands including Bain & Company, KPMG and Cap Gemini. Previously, he taught at Brandeis, Tufts and Gordon College. As an active member of Grace Chapel in Lexington, MA, he has led a special needs ministry for the past 12 years. He is widely published in the areas of the effectiveness of microfinance, healthcare data analytics and how Christian executives praise God through business. He holds a master’s from MIT and a Doctor of Management from Case Western.

NOTES

1 Milton Friedman, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to In- crease its Profits,” In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance, eds. Walther Zimmerli, Klaus Richter & Markus Holzinger (Springer, Berlin, 2007), 173-178.

2 Elisabet Garriga and Melé Domènec, “Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory,” Journal of Business Ethics 53(1-2) (2004), 51-71.

3 John Elkington, “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase ‘Triple Bottom Line.’ Here’s Why it’s Time to Rethink it,” Harvard Business Review 25 (2018).

4 Adrian King and Wil Bartels, “Currents of Change: The KPMG Sur- vey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting 2015”, KPMG International Cooperative (2015), accessed July 4, 2020 at https:/assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/pdf/2016/02/kpmg-in- ternational-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2015. pdf

5 Tomislav Klarin, “The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues,” Zagreb International Re- view of Economics and Business 21(1) (2018), 67-94.

6 Garriga and Domènec, “Corporate Social Responsibility.”

7 William M. Pride, Robert J. Hughes, and Jack R. Kapoor, Foundations of Business (Boston, MA: Cengage Learning, 2014).

8 See Bettina Lis, “The Relevance of Corporate Social Responsibility for a Sustainable Human Resource Management: An Analysis of Organizational Attractiveness as a Determinant in Employees’ Se- lection of a (Potential) Employer,” Management Revue (2012), 279- 295; A. Russo and P. Francesco, “Investigating Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital: CSR in Large Firms and SMEs,” Journal of Business Ethics 91(2) (2010), 207-221; and H. Garrett, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162(3859) (1968), 1243-1248.

9 See Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (Vol. 1., Homewood, Ill: Irwin, 1963), and Frederick Taylor, The Principles of Scientific Management (New York: Harpers & Brothers, 1911).

10 Abraham Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review 50 (1943), 370-396.

11 Douglas McGregor, and Joel Cutcher-Gershenfeld, The Human Side of Enterprise (Mew York: McGraw-Hill, 1960).

12 William G. Ouchi, Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge (Reading, MA.: Addison-Wesley, 1981).

13 Richard Boyatzis and Annie McKee, “Intentional Change,” Journal of Organizational Excellence 25(3) (2006), 49-60.

14 See R. Edward Freeman, Jeffrey S. Harrison, Andrew C. Wicks, Bidhan L. Parmar, and Simone De Colle, Stakeholder Theory: The state of the Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010); also Archie Carroll, “A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance,” Academy of Management Review 4 (1979), 497-505.

15 Jill Brown, and William Forster, “CSR and Stakeholder Theory: A Tale of Adam Smith,” Journal of Business Ethics 112(2) (2013), 301- 312.

16 Charles Handy, Myself and other More Important Matters (New York: Amacom Books, 2008).

17 On Common Goods Theory see Tim Hindle, “Triple Bottom Line. It Consists of Three Ps: Profit, People and Planet,” The Economist (17, 2009), accessed December 16, 2019 at https:/www.economist. com/news/2009/11/17/triple-bottom-line. For Theory of Externalities see William Baumol and Wallace E. Oates, The Theory of Environmental Policy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988); and for Theory of the Commons see William Buzbee, “Recognizing the Regulatory Commons: A Theory of Regulatory Gaps,” Iowa Law Review 89 (2003), 1.

18 John Fancis Mahon and Richard McGowan, Searching for the Common Good: A Process Oriented Approach (Boston, MA.: Boston University, School of Management, 1991).

19 Oliver Falck and Stephan Heblich, “Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing Well by Doing Good,” Business Horizons 50(3) (2007), 247- 254.

20 See Jeremy Harn, “What Does Praising God Mean?” Biblical Authority Devotional: Praise God, Part 4, Answers in Genesis, Biblical Authority Devotional (February 17, 2011), accessed June 3, 2020 at https:/answersingenesis.org/answers/biblical-authority-devotional/what- does-praising-god-mean/.

21 “Praise,” Baker’s Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, accessed June 4, 2020 at https:/www.biblestudytools.com/dictio- nary/praise/. Quoting Isaiah 43:21, New International Version, Bible Gateway, Accessed June 3, 2020 at www.biblegateway.com.

22 C.S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Jovanovich, 1964).

23 The Westminster Shorter Catechism, Westminster Assembly (1646), accessed June 16, 2020 at https:/bpc.org/wp-content/up- loads/2015/06/d-scatechism.pdf.

24 See Justin Taylor, C.S. Lewis in the Theology and Practice of Worship, the Gospel Coalition Blogs, accessed June 10, 2020 at https:/www. thegospelcoalition.org/blogs/justin-taylor/c-s-lewis-on-the-the- ology-and-practice-of-worship/.

25 “Praise,” Baker’s Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, accessed June 4, 2020 at https:/www.biblestudytools.com/dictio- nary/praise/. Citing 1 Chron 16:4, 1 Chronicles 23:4, and 1 Chronicles 23:30.

26 R.C. Sproul, “From Praise to Praise,” Ligonier Ministries, accessed June 10, 2020, at https:/www.ligonier.org/learn/devotionals/ praise-praise/.

27 “Billy Graham’s Life & Ministry by the Numbers,” Facts & Trends, accessed June 5, 2020 at https:/factsandtrends.net/2018/02/21/ billy-grahams-life-ministry-by-the-numbers/

28 Search for “marion e. wade” using google.com on June 5, 2020.

29 Marion E. Wade, and Glenn D. Kittler, The Lord is My Counsel: A Businessman’s Personal Experiences with the Bible (Upper Saddle River, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1966).

30 “Core Values,” accessed June 5, 2020 at https:/www.patagonia. com/core-values/.

31 Akira Nishimura, Management, Uncertainty, and Accounting: Case Studies, Theoretical Models, and Useful Strategies (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). See for example page 9 et seq.

32 Timothy Slaper and Tanya J. Hall, “The Triple Bottom Line: What is it and How Does it Work,” Indiana Business Review 86(1) (2011), 4-8.

33 “About B Lab,” accessed June 4, 2020 at https:/bcorporation.net/ about-b-lab.

34 “B LAB Impact Assessment, Step 1. Assess Your Impact, Sample Questions,” accessed July 9 at https:/bimpactassessment.net/ how-it-works/assess-your-impact#see-sample-questions.

35 “2019 Walmart Environmental, Social & Governance Report: Metrics,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/corporate.walmart.com/esgreport/.

36 “The 100 Most Visible Companies,” The Harris Poll (2019), accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/theharrispoll.com/axios-harrispoll-100/#.

37 See “Boost Awards, List of International CSR Awards & International Green Awards,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/awards-list. com/international-business-awards/corporate-social-responsibility-csr-awards/; and “2020 SEAL Business Sustainability Awards, SEAL Awards,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/pro.evalato. com/2289.

38 “Alphabet, Citigroup and Walmart named among global leaders on corporate climate action in CDP climate A List,” CDP: Disclosure Insight Action, accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/www.cdp.net/en/ articles/media/alphabet-citigroup-and-walmart-named-among- global-leaders-on-corporate-climate-action-in-cdp-climate-a-list.

39 “Great Place to Work: Mission Monitor,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/www.greatplacetowork.com/about.

40 Al Erisman and Denise Daniels. “The Fruit of the Spirit: Application to Performance Management,” Christian Business Review (2013), 27- 34.

41 Dave Kahle, “God in Your Foundational Statements,” Business as Mission: The BAM Review (2018), accessed June 16, 2020 at https:/ businessasmission.com/god-in-your-business-value-statements/.

42 Each of the examples in the paragraph are described in Barbara Farfan, “Retail Company Mission Statements with Religious Values,” The Balance Small Business (2019), accessed June 16, 2020 at https:/www.thebalancesmb.com/retail-company-mission-state- ments-religious-values-2891764.

43 Hobby Lobby, “Our Story,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/ www.hobbylobby.com/about-us/our-story#:~:text=We%20are%20 committed%20to%3A&text=Serving%20our%20employees%20 and%20their,and%20investing%20in%20our%20community.

44 See “Eventide Purpose and Values,” accessed December 18, 2019 at https:/www.eventidefunds.com/purpose-and-values/; Cision PR Newswire, “Eventide Launches the Eventide Global Dividend Opportunities Fund, 2017,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/www. prnewswire.com/news-releases/eventide-launches-the-even- tide-global-dividend-opportunities-fund-300530980.html; and “Invest with Us, Eventide: Creating True Value,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/www.eventidefunds.com/creating-true-value/.

45 See IBEC Ventures, “About Us: Serving the BAM Community Since 2006,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/ibecventures.com/about/; Larry Sharp, Triple Bottom Line #3: A BAM Business Seeks to Make Followers of Jesus, (2016), accessed December 18, 2019 at https:/ ibecventures.com/blog/triple-bottom-line-3-a-bam-business- seeks-to-make-followers-of-jesus/; and IBEC Ventures, “About Us: Serving the BAM Community Since 2006,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/ibecventures.com/about/.

46 “Business with a Purpose has the Willpower to Transform Society,” Impact Foundation, accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/impact- foundation.org/about-us.

47 Partners Worldwide, “About Us,” accessed June 22 at https:/ www.partnersworldwide.org/about-us/, and David Morgan, “Glob- al Indicators and Annual Impact 2017-2018, Partners World- wide,” accessed June 19, 2020 at https:/www.partnersworldwide. org/2018/10/08/creating-new-jobs-every-hour-of-the-day/.