[By Joshua Strakos, Blaine McCormick, and Matthew Douglas, 2019]

Abstract

Modern supply chains have global influence in the areas of social justice, human flourishing, cost management, and environmental impact. Since supply chains involve multiple entities, relationships, government agencies, and consumers, the effects of supply chain management decisions are far-reaching. Rarely, if ever, has supply chain management been framed in a theological context. In this paper, we bring together biblical principles concerning the character of God using a Christian ethics framework and illustrate how good supply chain management practices and policies can illuminate attributes of God’s character. Although the cases presented are secular for-profit companies, they illustrate the order-bringing nature of supply chain management, bringing it into a richer spiritual context. For the practitioner, this could mean ways for bridging the Sunday (worship) and Monday (work) divide. For the academic, the idea of tying operational excellence to social and spiritual outcomes can be a lens through which we examine sustainability issues and suggests a pedagogy for inspiring a new generation of supply chain leaders.

* The authors wish to thank the journal editor and reviewers of this manuscript for their seasoned advice and guidance regarding this paper. We would also like to give a special word of thanks to Dr. Marjorie Cooper, our esteemed colleague here at Baylor. Dr. Cooper’s wisdom and insight into how Supply Chain Management can be viewed in the context of Christian ethics was elemental in our revision process.

Introduction

Supply chain management encompasses the planning and management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement, conversion, and all logistics management activities.1 We add to this scope by including the disposition of goods in the post-consumer stage, whether that be recycling, remanufacturing, reuse, or waste. The notion of the circular economy is emphasized here, where there is little to no waste created by the supply chain. Also, the design and transformation of products and services, along with their delivery, is managed in a way that makes the most effective use of all resources – not just for the good of the financial bottom line and short term, but for social and environmental dimensions and with a long-term view guiding decision-making.2 Supply chain management is a far-reaching and broad business discipline both within the firm and external to the firm. Practically, supply chain activities impact customer service and cost; improve the financial position of the firm; ensure human survival; improve quality of life; and protect cultural freedom and development3. Our goal in this paper is to frame supply chain management as a way to exhibit the character of God in society, as illustrated by cases in the areas of logistics and total supply chain management, procurement, and transformation and manufacturing. Just as modern medicine is often viewed as an extension of God’s healing power, supply chain management is a body of knowledge which has been given to us and can be used as a tool to serve the needs of others and glorify God by manifesting attributes of His character – particularly that of creating order out of chaos.

Hill contends that acting ethically is a matter of knowing and enacting the character of God.4 For Hill, this is a holiness-justice-love triad. That is, God is a God of holiness, a God of justice, and a God of love. Hill acknowledges that God has other facets to His character such as artistry or orderliness. Thus, as God is a God of order, then order is part of the character of God, and this is revealed in God-directed events like an orderly creation story, an orderly exodus from Egypt, or an orderly listing of laws and commands for His people. As such, it is ethical for Christians to live orderly lives and promote order in the world. A wide variety of commentaries note the explicit order as part of the creation story in Genesis. Walton notes that in the text of Genesis 1, God’s initial work dispelled the chaos and brought everything into perfect order and equilibrium”5 and also that “…there is a clear establishment of order from disorder.”6 Kass notes that the Genesis text also denotes a hierarchical ordering of the world beyond that of making order out of disorder, for example, “…living things are higher than non-living things…”7 Kass also notes that present-day evolutionary theory possesses a “hierarchy-blind character,” which rejects this ordering in favor of a more random and disordered world.8 The theme of order continues into the New Testament with an orderly dissemination of the Gospel from “…Jerusalem, Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth”9 and orderly management of households in the letters of Paul.

In this paper, we embrace Hill’s ethical framework to present supply chain management as a discipline with the potential to manifest the orderly character of God. Additionally, as order is created out of chaos, then the potential for justice, love, and holiness increases. Justice, love, and holiness, in turn, help maintain the ordered systems which have emerged.

ORDER FROM CHAOS

Christian ethics in modern business is a challenging topic, especially since the business world is focused on profit before piety. The challenge involves applying Christian ethics in a way which focuses on glorifying God rather than being legalistic, permissive, or even acting justly without regard for holiness. As we explore how applying justice, holiness, and love within the supply chain helps to amplify the character of God by bringing about order, we hope to open the conversation about the relevance of Christian ethics as applied to supply chains. As Alec Hill discusses in Just Business, the application of Christian Ethics is irrelevant and ineffective in its pursuit of bringing glory to God if it is done in a simplistic, rules-based way.10 Supply chains, by their very nature, present us with some incredibly complex scenarios – scenarios in which the application of biblical principles requires depth of thought as well as a framework such as Hill’s justice, holiness, and love structure.

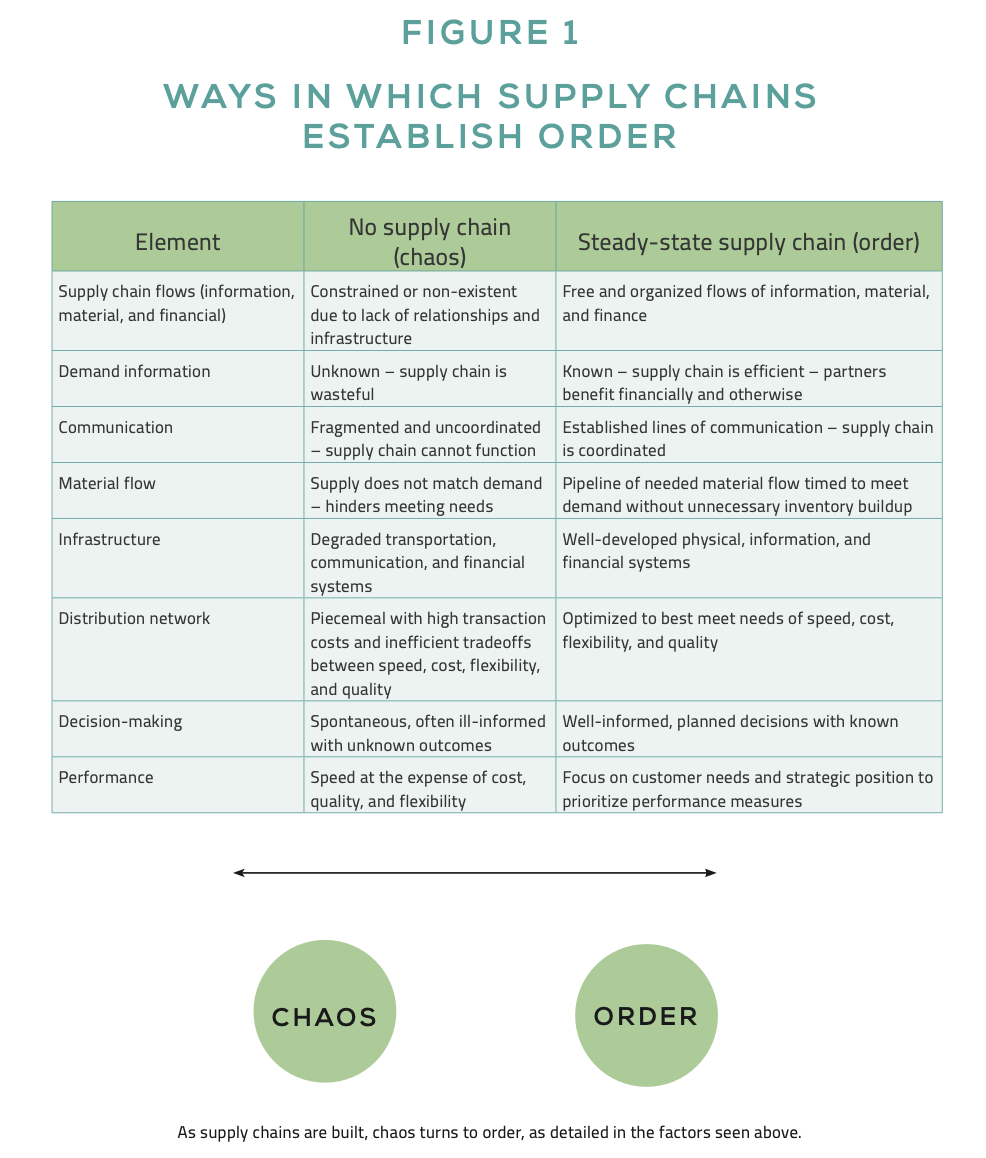

Supply chains and their development inherently bring order to chaos. An extreme example of this evolution can be seen in the aftermath of a disaster, when established supply chains do not exist, infrastructure is degraded or non-existent, communication is difficult, and needs are dire yet often unknown at the onset of the relief effort. A typical large-scale response may involve herculean logistics efforts. Approximately 80% of disaster relief relies on logistics.11 For example, the response to Hurricane Harvey involved over 31,000 federal employees, 3 million bottles of water, 9,900 blankets, 8,480 cots, and 300 volunteer organizations, not to mention the care of animals, administrative work for insurance claims, and private businesses which participated.12 Supply chain management has been defined as a process which involves the flows of information, material, and finances and the management of these flows from raw material to the end user.13 This process becomes refined and efficient (ordered) as information sharing and financial relationships are built, shipping routes are established, demand forecast information stabilizes, and timelines become known. In the immediate wake of a disaster, this process and the dynamic environment in which it exists is necessarily chaotic. Neither the relationships and information mentioned above, nor the exact nature of demand is established following a disaster event. In fact, even the well-intentioned surge of donated goods (often the wrong goods) serves as a hindrance to the overall management of information, material, and finances to the point where it is often referred to as “the second disaster” by relief workers,14 and contributes to the chaos. The point of this discussion is to show the inherent order-bringing nature of supply chains and illustrate the extremes between well-ordered supply chains and the chaotic environment of a post-disaster scenario where no supply chain is established.

As supply chains emerge, chaos turns to order with greater potential for just, holy, and loving acts to occur. In contrast, as supply chains disintegrate, chaos begins to overturn order with behaviors like price-gouging, bribery, favoritism, and stockpiling. The visible hand of ethical supply chain management can often motivate and promote behaviors that the invisible hand of the marketplace cannot.15

As illustrated in Figure 1, in a disaster response scenario, order begins to emerge from chaos as various supply chain

factors become established and the environment returns to normal after a disaster. However, a steady-state environment does not guarantee a well-ordered supply chain. Supply chains are complex and combine many competing interests; therefore, many factors can degrade the integrity of a supply chain. Hill’s framework of justice, holiness, and love can be applied to show how these guiding principles, when applied to supply chain management, can bring about order by establishing and maintaining the integrity of the supply chain. This emphasizes the importance of decisions made by ethical actors to both establish and maintain an ordered supply chain.

One of the goals of supply chain management is to maximize supply chain surplus.16 Supply chain surplus is defined as the difference between the value created for the customer (think revenue) and the total cost incurred by the supply chain to produce and deliver the item to a customer. This is like Porter’s value chain concept, in which value is added and cost is incurred at each stage of the supply chain. Unless a supply chain is 100% vertically integrated, this involves many entities, usually with competing interests. The sharing of information, trust, and coordination required for everyone to act in the interest of the system (rather than in the interest of only themselves) is difficult to achieve, however, when each actor elevates the goal of the system above his or her own selfish interests. The overall supply chain surplus is likely to be maximized, and all stages will benefit more if they had not put their own interests first.

To achieve this level of supply chain coordination, decision-making must revolve around the supply chain rather than the individual (or individual firm). The application of the justice, holiness, and love Christian ethics framework may serve as a practical guide to enacting this type of coordination and, thus, order.

The remainder of this paper will focus on an illustration of how supply chain management, under the umbrella of Hill’s ethical framework, might serve to bring and maintain order in society through management practices. The illustrations illuminate three focus areas of the discipline of supply chain management, including logistics, sourcing and procurement, and transformation (manufacturing). Our hope is for Christians to see supply chain management work in a richer theological context not previously explored.

LOGISTICS MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES

Logisticians are charged with getting the right thing, to the right place, at the right time. “Well-informed”

logisticians can meet diverse requirements effectively, with minimal resources. Life’s necessities, such as food,

clothing, shelter, and medical supplies, crisscross the world to close critical demand gaps and sustain an ever-demanding population every day. However, establishing an effective supply chain encompasses more than logistics. Networks of suppliers, information systems, and human capital must be established and maintained.

Innovations in transportation and distribution are becoming more prevalent, as technology has disrupted

traditional distribution methods to meet important needs that were previously underserved. For example, consider

Zipline, a company that “delivers medicine to those who need it most.”17 Zipline identified an important need in developing countries. Particularly, blood transfusions constitute one of the most common medical procedures. Blood is a rare resource with a limited shelf life, and as a result, blood needs to be distributed from donors to recipients in the shortest amount of time. This process requires efficient and effective transportation and delivery, or people die.

In developed countries, to ensure zero stockouts, the blood supply issue is handled with high levels of stock. However, this practice is incredibly expensive and can be wasteful. Developing countries don’t have the luxury of managing blood donation and distribution in this manner. So Zipline developed an innovative solution in Rwanda to deliver blood via autonomous drones.18 This process is more efficient, as this delivery mechanism can overcome barriers such as poor road infrastructure. Additionally, blood is stored at a small number of centralized distribution centers, versus at every hospital, which allows for more flexibility and efficiency in matching demand with supply. As added benefits, the delivery system requires a small footprint (the launch site no bigger than a football field) and local employees operate the system, bringing value to local economies.

Zipline claims to have saved more than 10,000 lives thus far. What’s more, this system can be scaled to deliver other

medical products (such as medicines) and support disaster relief operations with expeditionary launch sites. Efforts are underway to expand networks to share resources across launch sites and distribution centers, which will further

improve efficiency and enhance sustainability. Zipline operates a commercial supply chain comprised of

donors, distribution centers, a transportation and operations network, hospitals, information systems, and local teams. The donors serve as the source of raw materials, and the hospitals, doctors, and, ultimately, patients are the customers in need. In closing the gap between this demand and supply, Zipline illustrates the application of Hill’s ethical framework, even though the company is not overtly philanthropical.

We can see the breakdown of how the elements of the framework are applied in the following way. Holiness is considered a zeal or single-minded focus on God and purity in decision-making. Even the slightest compromise of

honesty, values, or mission will pollute the purity of holiness and contribute to the degradation of an ordered

supply chain. Zipline’ mission is to provide every human on earth with instant access to vital medical supplies. The

company’s founder discusses how they are using cutting- edge technology in technology-starved countries to accomplish this mission. A compromise to the mission would mean being willing to accept that there are areas where this technology is just too difficult to implement. Instead, Zipline develops systems which fit and optimize local resources like cell phone networks, off-the-shelf communications applications, and local labor. Instead of thwarting their growth and mission accomplishment, their unwillingness to compromise the mission (holiness) makes them unique and successful –actually driving innovation to succeed where other logistics providers don’t even consider doing business. Justice is also present in this mission in that Zipline, by providing blood to areas where it is extremely difficult to travel, is providing the basic human right to life to those who may otherwise be ignored by other medical logistics providers because of the operational challenges in these areas.

Interestingly enough, Zipline is not a charity. They are not a philanthropic organization. They are a for-profit company

operating in a space usually occupied by donor-funded humanitarian organizations. However, in recognizing that

there is an opportunity to both serve and help others as well as make a profit, they are effectively trading charity

for the economic sustainability of operations. Zipline will be able to bring their model of an ordered supply chain to

many other chaotic and challenging areas because of their for-profit structure. Some might see this as entrepreneurial opportunism; however, it can also be viewed in the context of showing love. Love is exhibited by showing mercy and sacrificing one’s own rights for the rights of others. However, love is not a carte-blanche license to give up all our rights, justice, or holiness to others. That would be permissiveness or simply “being a doormat.” By never compromising their mission, enabling the rights of others, yet doing so in a way which is sustainable, Zipline is exhibiting love.

To elaborate, Zipline, by taking a long-term view, may be sacrificing in the short-term. They could probably be making more money in locations where the conditions would allow for greater economies of scale. However, Zipline’s model results in a system that they can grow internally and use to provide lifesaving medical supplies to many areas otherwise impossible to reach effectively. The benefits of this supply chain go beyond simply supplying blood to patients and profitability for Zipline. By reducing inventory and speeding delivery and communication, Zipline makes the tradeoff between waste and access better for everyone. Lower inventory through centralization means less capital and less spoilage. Before Zipline, Africa didn’t have the transportation infrastructure to make this an effective tradeoff. Their success also drives compounding gains. As mentioned, the system reduces waste. Additionally, it has benefitted Rwanda by establishing an aerial logistics network, employing locally hired teams, producing technological innovations, and operating in a way that is 100% scalable and self-sustaining (because it is not donor-funded philanthropy).

The use of local teams and information networks provides a boost for local economies and fosters entrepreneurship, which lifts people out of poverty. By focusing on the good of the system and implicitly applying a Christian ethical framework, Zipline elevates the good of an entire supply chain above its own ambition to create something that brings order for the benefit of all. This is only one of many examples of logistics management as a redemptive practice, yet in each case, logisticians meet critical needs and impact lives. Here is a sample:

- It is common in North America to give fresh cut roses to our most beloved on a holiday in the middle of winter – Valentine’s Day. Few of us stop to consider that the roses are grown and harvested in warm climates below the equator, flown into airport hubs, approved through customs, transported to retail outlets, and made available for purchase in 12 days or less.

- Bananas remain the top-selling food at Walmart (U.S.) year after year and – as importantly – month after month. Most bananas are grown within 20 degrees on either side of the equator – well outside of the footprint of the continental United States.

- Consider the democratization of common table salt and pepper. In earlier times, conflicts were waged in an effort to control the trade of rare spices – like black peppercorns – that made bland food taste better. Salt was so valuable in earlier times that it formed the root of our word “salary.” Now, both are available as free condiments at any neighborhood convenience store.

SOURCING AND PROCUREMENT ACTIVITIES

More and more retailers – from restaurants to grocery stores – are discovering the importance of supply chain visibility and transparency. Many have discovered that consumers want to know where their food or products come from and whose hands they have touched. A recent article, which highlighted how child labor is being used in the cocoa trade,19 aims to spur us on to act justly, demonstrate love, and show purity by rejecting the companies in an industry that is not responsibly sourcing their products. The naming of names across a supply chain and making stories of supply more visible certainly call us to display the character of God. Although stories like the one about injustice in the cocoa trade motivate us to make changes to the negative, there are also plenty of positive examples of supply chain visibility in procurement practices. Consider the following three cases.

HEB is a dominant grocery retailer near the authors’ university. It is a practice at HEB to profile the names and families of suppliers for various products. It did not take long to identify beef suppliers (The Peeler Family Ranch and Graham Land and Cattle), squash and tomatoes (Mark Fikes and his family near Fredericksburg, Texas) and blueberries (the Beard family at Creekwood Farms near Vidor, Texas). These and other suppliers are highlighted with the names and descriptions of the work they do to create supply for consumers

Walmart increasingly makes supplier stories visible to consumers. Interested readers can find stories about their Mexican-style tortillas produced by Ole Mexican Foods and its founder, Veronica Moreno. Patricia Wallwork is a third-generation family member and currently serves as CEO of Milo’s Tea Company just outside of Birmingham, Alabama.

Fishpeople brand seafood from the Pacific Northwest includes on the packaging the names and photos of some of the fish workers who help bring in each catch sold through the brand label. Via the package or a code to use on the internet, one can easily learn about people like Captain Sean Harrigan of the fishing vessel, Courageous, who helps source Alaskan Cod, or Carlie Fitka, a Yupik fisherman who works the lower Yukon River to bring in Wild Yukon River Keta Salmon.

These examples illustrate the very nature of why supply chains exist. It would be impossible for Walmart or HEB to produce all the products they supply. However, it would also be difficult for local fisherman and farmers to sell their products as effectively as the retailers. This illustrates the way supply chain partners work together for the good of all, like the workings of the body of Christ. These partnerships elevate the good of all above the individual good, resulting in an ordered, coordinated effort which benefits all. Continuous ethical management input is required to prevent a well-ordered supply chain from falling into disorder. The supply chain manager influences the maintenance of order (or not) in seemingly local and everyday management decisions.

Here’s a final comment on how something as obscure and bureaucratic as procurement policies can be a redemptive force in society. Boeing’s Conflict Minerals Policy20 explicitly announces that its sourcing of tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold will be from conflict-free sources. Further, should Boeing become aware of any instance where the supply chain for these necessary minerals is used to finance armed groups, they will work to find a conflict-free alternative source. IBM’s conflict minerals policy is similar in its Global Procurement function. Surely, these simple but wise policies support the spread of justice throughout the globe.

CONVERSION ACTIVITIES

In contrast to the more localized Zipline supply chain, we can also see the order-bringing nature in larger enterprises. Companies producing consumer goods range from smaller, vertically integrated manufacturing lines with few external suppliers to large multinational “hollow corporations” which fully rely on contract manufacturers to produce their goods. Finding efficiencies to enhance global competitiveness becomes an intense managerial focus, which can become non-congruent with the application of holiness, justice, and love. Although many global supply chains operate under strict codes of conduct for their suppliers, these compliance activities become decoupled from core business practices and are more lip service than an integral part of the supplier selection process. Nike is an example of a large brand which is solely reliant on contract manufacturers to produce their products. Nike’s supply chain includes 463 factories in 41 countries which employ 1,005,671 employees to produce their finished goods.21 To say Nike’s transformation process has a far-reaching global influence is an understatement. Large supply chains like Nike’s have been criticized for encouraging poor labor practices in developing markets where labor costs are low and regulations are less stringent than in developed countries.22 Beginning in 2007, Nike introduced lean supply chain interventions into some of its manufacturers’ supply chains in an effort to improve supplier capabilities. What resulted, however, was a surprising benefit to social outcomes.

The lean implementations in Nike’s supply chain were aimed at production improvements rather than any specific labor, health, or environmental issue. The lean program did not include training suppliers to meet social standards or to avoid social sanctions via audits. Rather, the key expected outcomes were a more efficient, less wasteful supply chain with obvious bottom-line benefits. However, Nike found that lean management tools ended up improving labor standards for workers in emerging market manufacturers.23 After lean implementation, workers experienced better wages, less verbal abuse by supervisors, improved grievance systems, guaranteed time off, and better benefit systems. The available evidence indicates that lean management activities during the transformation process promote workplace justice in ways that might surprise stakeholders who prefer a more sanction-based approach to workplace improvement.

These findings mirror those found in the World Management Survey.24 This ambitious, decade-plus research program documented management practices across the globe and enabled researchers to compare outcomes and practices across countries. Researchers collected data from managers in charge of production and transformation processes at manufacturing plants. Lean processes were, once again, a key area of inquiry for the research teams. The WMS research outcomes strongly suggest that poor management practices are a key contributor to low productivity in many emerging market economies. Research documenting clear and positive improvements when lean management processes were introduced into low performing plants25 once again confirms the social impact of good management during the transformation process.

It may not be apparent that Christian ethics played a part in this story of unexpected outcomes. What we’d like to focus on here is the impact of management decisions in the manufacturing process on the social justice outcome. Without the management intervention of lean implementation, the factory working conditions, as well as the overall efficiency and productivity of the manufacturing activities, would have continued to degrade. The illustration is to again show how the guiding management decisions have ripple effects and compounding benefits across supply chain partners. In addition to improving the financial outcomes for Nike, the lean management decisions also benefitted the manufacturers’ and their employees directly.

The management decisions made under lean principles are like those guided by holiness, justice, and love. Lean principles require discipline and strict adherence to standards (holiness). The lean philosophy also requires a long-term focus, which sacrifices short-term profit maximization. An example of this is a lean-focused company’s laying off of employees only as a last resort, even in times of economic slowdown. Although this requires an immediate sacrifice of rights (love) on the employer’s part, it also promotes sustainability and employee trust by maintaining trained and loyal employees. It also invokes justice in that employees are expected to share some of the burden of the slowdown by working reduced hours for reduced pay. This is not to say lean principles can take the place of an intentional focus on holiness, justice, and love. However, it again illustrates the order-maintaining impact supply chain managers’ decisions have in the transformation and manufacturing areas of the supply chain.

CONCLUSION

“Each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms” (1 Pet. 4:10, NIV). Supply chain management and its functions are not commonly referred to in a theological context as an embodiment of God’s character in this world. God’s calling to us clearly extends to how we use the gifts and skills he has given us to work for His glory in serving others.26 We may think of concepts such as holiness, justice, and love as godly mandates, which can be difficult to integrate into the workplace. However, we believe the character of God can be exhibited through the actions of meeting basic needs like food, clothing, medicine, and human flourishing in the most developed, as well as the least developed, places. We showed how the supply chain manager’s influence extends to Texas farmers, Atlantic fisherman, African miners, Asian factory workers, remote and undeveloped areas, and beyond. As managers of an influential and economically powerful network, we can use policy, recognition, and operational enhancements to bring economic value to stakeholders while simultaneously enhancing the quality of life for supply chain partners, consumers, and communities. Corporate giants HEB, Walmart, Boeing, and IBM promote justice and love in their consumer-supplier connections and procurement policies. Nike has taught the world that world-class manufacturing practices not only transform materials into products we love but also the workplace environment, bringing justice to low-wage areas where manufacturing is primarily cost-focused. Zipline uses a sustainable logistics model coupled with innovative drone technology to make medical products available in remote parts of Africa where cost and infrastructure have been limiting factors. Although the cases presented here only give us a brief glimpse into the supply chain world, the ideas may be used to shed light on how we approach economic, environmental, and social aspects of sustainability, with a focus on social justice issues. Future research should continue to look at specific mechanisms by which supply chain practices exhibit God’s character by bringing order to chaotic environments. This can be done from a variety of perspectives: the worker, the employer, the supplier, the consumer, and so on. There is a wealth of research on supply chain environmental sustainability. However, research on supply chain social sustainability is a much less developed, and often-neglected, area of the triple bottom line.27

Make no mistake, however, the examples presented here are not charities. Regardless of their company values, they cannot continue to exist without economic sustainability. We simply argue that by working within these and other like-minded organizations, we can exhibit holiness in our work by serving in the world while not being of the world. That is, you can give God glory in secular pursuits. In fact, that is the very point of these thoughts – to close the gap between our daily work and the glorification of God, which is sometimes viewed as a Sunday-morning exclusive. In that light, we offer the following closing thoughts to practitioners and academics.

For the practitioner, the implications are that while working from the supply-side perspective, we ought not to compartmentalize what we do at work from who we are in Christ. Serving as an extension of the true vine to bear fruit in the world is no task that can be confined to a sanctuary or place of worship. There are cultural expectations to secularize business pursuits and to filter out any allusions to the God of the Bible from our speech and action at work. This spiritual function must be as much a part of our work as the physical work we do to buy, make, and ship products in the supply chain. Hopefully, we have illustrated how to more effectively integrate faith into supply chain management decision-making through the application of the holiness, justice, and love framework. The idea that supply chain management can display the orderly character of God in the business world gives hope of both what is to come and a deep purpose and meaning to our everyday work, especially in what we might otherwise think of as important, yet secular, pursuits.

For the academic, the idea that supply chain decision-making can have the profound spiritual effect of bringing order to a chaotic world sheds new light on how we approach the current hot-button issues of sustainability, corporate social responsibility, and cost-management from a biblical stewardship perspective. As teachers, in passing along knowledge and skills to a new generation, of which the U.S. supply chain accounts for 37 percent of all jobs,28 this gives deeper meaning and purpose to this foundational part of the economy. To students, supply chain sustainability can be a broad and hard-to-grasp concept that sometimes brings only thoughts of poor labor practices, dirty warehouses, or pollution-emitting factories. In taking a stewardship-based approach to teaching supply chain management, which intentionally incorporates holiness, justice, and love into decision-making, we can help guide the next generation of professionals toward a holy calling – one in which daily decisions are made within a framework that offers opportunities to manifest God’s character throughout the supply chain, with far-reaching influence on social justice and human flourishing.

Notes

1 ”CSCMP,” SCM Definitions and Glossary of Terms, accessed February 26, 2019, https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921

2 Mark Esposito, Terence Tse, and Khaled Soufani, “Introducing a circular economy: new thinking with new managerial and policy implications,” California Management Review 60, no. 3 (2018): 5-19.

3 “The Importance of Supply Chain Management,” accessed February 26, 2019,https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Develop/Starting_Your_SCM_Career/Importance_of_SCM/CSCMP/Develop/Starting_Your_Career/Importance_of_Supply_Chain_Management.aspx?hkey=cf46c59c-d454-4bd5-8b06-4bf7a285fc65

4 Alec Hill, Just Business: Christian Ethics for the Marketplace (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2008).

5 John Walton, The NIV Application Commentary–Genesis (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2001), 65.

6 Walton, NIV Application Commentary–Genesis, 65.

7 L.R. Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom (New York: Free Press, 2003), 36.

8 Kass, The Beginning of Wisdom.

9 Acts 1:8

10 Hill, Just Business, 12.

11 Luk Van Wassenhove, “Humanitarian aid logistics: supply chain management in high gear,” Journal of the Operational research Society 57, no. 5 (2006): 475-489.

12 FEMA, “Historic Disaster Response to Hurricane Harvey in Texas,” accessed June 11, 2019, https://www.fema.gov/news-release/2017/09/22/historic-disaster-response-hurricane-harvey-texas

13 Gyongi Kovacs and Karen Spens, “Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 37, no. 2 (2007): 99-114.

14 Scott Simon, “Best Intentions: When Disaster Relief Brings Anything but Relief,” Last modified September 3, 2017, https:// www.cbsnews.com/news/best-intentions-when-disaster-relief-brings-anything-but-relief/

15 Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. The Visible Hand (Boston: Belknap, 1977).

16 Sunil Chopra and Peter Meindl, Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation (London: Pearson, 2015).

17 “About Zipline,” accessed February 26, 2019, https://flyzipline.com/about/

18 Wendover Productions, “The Super-Fast Logistics of Delivering Blood by Drone,” video, 13:31, January 25, 2019,

https://youtu.be/bnoUBfLxZz0.

19 Peter Whorisky and Rachel Siegel, “Cocoa’s Child Laborers,” The Washington Post, June 5, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2019/business/hershey-nestle-mars-chocolate-child-labor-west-africa/?utm_term=.34569cb9719e

20 Boeing, “Boeing Conflict Minerals Policy,” accessed February 26, 2019, http://www.boeingsuppliers.com/Boeing_Conflict_Minerals_Policy.pdf

21 Nike, “Nike Manufacturing Map,” accessed February 18, 2019, http://manufacturingmap.nikeinc.com/#

22 Debra Schifrin, Glenn Carroll, and David Brady, “Nike: Sustainability and Labor Practices, 1998–2013,” Case Study, Stanford Graduate School of Business (2013).

23 Greg Distelhorst, Jens Hainmueller, & Richard M. Locke, “Does lean improve labor standards? Management and social performance in the Nike supply chain,” Management Science 63, no. 3 (2016): 707-728.

24 WMS, World Management Survey, accessed February 26, 2019, https://worldmanagementsurvey.org/

25 Nicholas Bloom, Raffaella Sadun, & John Van Reenen, “Does management really work?” Harvard Business Review 90, no. 11 (2012): 76-82.

26 John 15:1-5

27 John Elkington, “25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase ‘Triple Bottom Line.’ Here’s Why It’s Time to Rethink It,” Harvard Business Review Digital Article, June 25, 2018, https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it

28 Mercedes Delgado and Karen Mills, “The Supply Chain Economy and the Future of Good Jobs in America,” Harvard Business Review Digital Article, March 9, 2018, https://hbr.org/2018/03/the-supply-chain-economy-and-the-future-of-good-jobs-in-america

About the Authors

Joshua Strakos is Clinical Assistant Professor of Management at Baylor University. He earned a Ph.D. in Operations Management from the University of Houston and is a 20-year Air Force veteran with a background in logistics and petroleum management. His research interests include humanitarian logistics, energy management, and teaching innovation. He serves as a faculty mentor for Baylor’s Supply Chain Management Program. He has been married for 23 years. He and his wife have two sons, one of whom is a 2019 graduate of Baylor University. He enjoys fishing and volunteers regularly with a youth gymnastics program in the Waco, TX area.

Joshua Strakos is Clinical Assistant Professor of Management at Baylor University. He earned a Ph.D. in Operations Management from the University of Houston and is a 20-year Air Force veteran with a background in logistics and petroleum management. His research interests include humanitarian logistics, energy management, and teaching innovation. He serves as a faculty mentor for Baylor’s Supply Chain Management Program. He has been married for 23 years. He and his wife have two sons, one of whom is a 2019 graduate of Baylor University. He enjoys fishing and volunteers regularly with a youth gymnastics program in the Waco, TX area.

Blaine McCormick serves as Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Management at Baylor University. Following a brief career in the energy industry, he earned his Ph.D. from Texas A&M University. His primary research expertise is the business history of Benjamin Franklin. For 2019, he serves as Chair of the Board for Waco’s Dr. Pepper Museum & Free Enterprise Institute. He greatly enjoys being in the field visiting businesses, where he can ponder the modern supply chain. He and his wife of 30 years, Sarah, live in Waco, TX.

Matthew Douglas is Assistant Professor of Management at Baylor University. He earned a Ph.D. in Marketing from the University of North Texas and is a 22-year Air Force veteran with a background in operations and logistics management. His research primarily addresses social sustainability issues in supply chains, with a focus on safety in transportation and operations. He has been married for 20 years, and he and his wife have two children (a daughter and a son). He enjoys traveling and outdoor activities, and he volunteers regularly with a local youth basketball program.

Matthew Douglas is Assistant Professor of Management at Baylor University. He earned a Ph.D. in Marketing from the University of North Texas and is a 22-year Air Force veteran with a background in operations and logistics management. His research primarily addresses social sustainability issues in supply chains, with a focus on safety in transportation and operations. He has been married for 20 years, and he and his wife have two children (a daughter and a son). He enjoys traveling and outdoor activities, and he volunteers regularly with a local youth basketball program.