By: Ronnie Chuang-Rang Gao and Kevin Sawatsky

ABSTRACT

This paper fills a gap in research on job satisfaction and motivational factors in faith-based organizations.

Drawing on motivational theories, we present a conceptual model that hypothesizes the effects of three factors (personal faith, perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith, and transformational leadership [TL]) on job satisfaction and the mediating effects of motivation. A statistical analysis of survey data from four Christian institutions of higher learning in Canada concluded that personal faith is positively related to job satisfaction, but only among employees high in perceived fit. We also confirm that motivation fully mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. In addition, TL has a direct effect on job satisfaction and an indirect effect through the partial mediation of motivation. Managerial implications of these findings are also discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Nehemiah is often viewed as a Biblical example of transformational leadership. He faced seemingly insurmountable, complex problems, while dealing with difficult people, yet was able to effectively motivate the team around him to achieve a vast rebuilding project. While the project was successful due to God’s providence, it was also successful because Nehemiah understood the factors that motivated the people with him. He understood the yearning to correct the historical disgrace from captivity and a destroyed Jerusalem (Nehemiah 4:17). Nehemiah understood the need for hope and the desire of his team to improve the future for their families (Nehemiah 4:14). He understood the economic challenges demotivating some of the people (Nehemiah 5).

Similarly, successful leaders of modern faith-based organizations (“FBO” or “FBOs”) must understand their employees and the factors that motivate them. It is surprising, that while much has been written with respect to motivational factors in corporations, little exploration has been done with respect to such factors in FBOs. In this research, we seek to begin this exploration by examining the effectiveness of just three motivational factors within the context of FBOs: employees’ personal faith, the perceived fit between personal and organizational faith, and transformational leadership. First, does personal faith itself make employees more satisfied with their jobs? If so, will motivation mediate this relationship? In other words, will stronger personal faith lead to higher employee motivation levels, which in turn will result in higher job satisfaction? Although research in organizational behavior has examined personal faith, this has largely been in the general work environment. Remarkably, we could not identify research that has explored the link between personal faith and job satisfaction and the possible mediating effect of motivation in FBOs.

The second motivational factor examined is the perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith. This is a new construct introduced in this study, which we define as the extent to which an employee perceives personal faith as consistent with that of the organization. Employees in FBOs often share the same religion but are not necessarily from the same sub-group within that religion and thus may have considerably different beliefs and practices. For example, Christianity comprises six major groups: Church of the East, Oriental Orthodoxy, Eastern Orthodoxy, Roman Catholicism, Protestantism and Restorationism. Protestantism alone includes many denominations that have diverging beliefs and practices, such as Adventism, Anabaptism, Anglicanism, Baptists, Lutheranism, Methodism, Moravianism, Pentecostalism, and Reformed Christianity.1 Organizations may also have varying commitment levels to the beliefs and practices of the religious sub-group they are affiliated with. Some may, therefore, perceive a high level of fit between their personal faith and the faith of their employer, while others perceive a low level of fit or no fit at all. Will the different levels of perceived fit lead to different levels of job satisfaction? If so, will motivation mediate this relationship? Again, no previous research seems to have examined these possible effects.

Third, considering the proposed motivating effects of personal faith and perceived fit, we examine if transformational leadership still impacts motivation and job satisfaction in FBOs. Prior research confirms the strong relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction in secular organizations.2 However, in FBOs, where people generally put God ahead of leaders, will the normal link between transformational leadership and job satisfaction still exist? If so, will motivation also mediate this relationship?

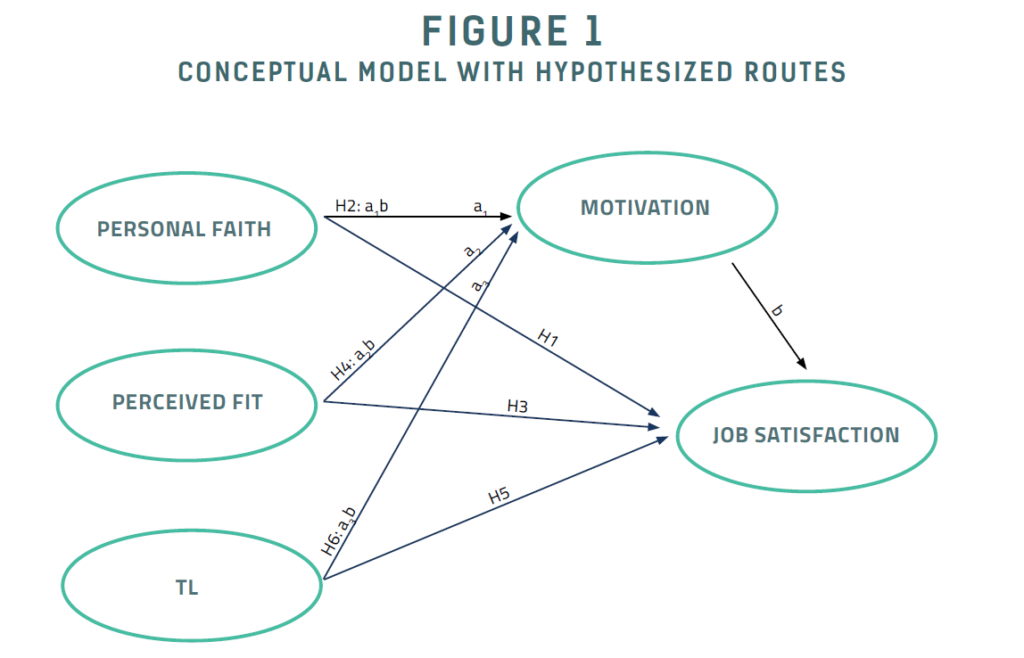

Drawing on three motivation theories, expectancy theory, 3 two-factor theory,4 and job characteristic theory,5 we present a conceptual model in which we assert that personal faith, perceived fit, and transformational leadership are each positively related to job satisfaction and that motivation mediates each relationship. We then test our conceptual model with a survey among faculty and staff in four faith-based colleges in Canada. (We are cognizant that there are many different types of FBOs and faith based colleges may not perfectly represent all such organizations. We acknowledge this limitation and encourage further research across a broader range of FBOs.) Finally, we endeavor to provide theoretical contributions and managerial implications.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

FAITH-BASED ORGANIZATIONS

While most people intuitively understand what a FBO is, there are varying definitions. Bradley argues that, for an organization to be considered faith-based, faith needs to be embedded in its operational structure.6 Bielefeld and Cleveland refer to FBOs as religiously influenced organizations with an explicit goal to provide social services.7 Clarke proposes that FBOs rest on two pillars: a conceptual-ideological pillar, which promotes social justice, peace, and development, and a programmatic pillar, which imbues ideology into practical social activities.8 Smith and Sosin identify three characteristics of FBOs: relying on religious entities for resources, affiliating with a religious group, and having a religious culture that creates a niche for the organization to pursue its religious values.9 In our research, an FBO simply refers to “an organization with a main purpose other than worship, but with some significant connections with a religious organization or tradition” (p. xi).10

PERSONAL FAITH

Personal faith has been shown to impact various job-related outcomes, including: work attitude;11 satisfaction with intrinsic, extrinsic, and total work rewards; organizational commitment; 11, 12 meaningfulness of work;13 ethical decision-making; 14 engagement in organizational citizenship behavior and less burnout;12 and accountability to the organization.15 Job stressors have more negative effects when employees have lower personal faith levels.12 Note that these faith-related studies took place in general work settings rather than FBOs.

The personal faith literature remains surprisingly silent on one question: in FBOs, is personal faith related to job satisfaction? We believed this relationship should exist. For employees high in personal faith, work is about searching for deeper meaning and expressing inner life needs and wants.16 Previous research shows that when people’s work-related wants, desires, and expectations are met, they are more satisfied with their jobs17 and that intrinsic influences, such as meaningfulness of work, have positive effects on job satisfaction.18, 19 In addition, employees high in personal faith are more likely to experience a sense of community when interacting with coworkers with the same religion. In other words, mental, emotional, and spiritual connections are likely to occur among these employees, which in turn will lead to a deeper sense of connection, mutual support, freedom of expression, and genuine caring among them.19 Linge and Mutinda found that good relations with coworkers are positively related to job satisfaction in FBOs.20 Thus:

Hypothesis 1

In FBOs personal faith is positively related to job satisfaction.

MOTIVATION

We believed, based on expectancy theory, that in FBOs motivation would mediate the relationship between personal faith and job satisfaction. That is, personal faith is positively related to the level of motivation, and this level is positively related to job satisfaction. Vroom’s expectancy theory of motivation proposes that people are motivated to select a specific behavior over others because they expect certain results from the selected behavior and that the motivation of the behavior selection is determined by the desirability of the outcome related to the behavior. Expectancy theory has three components: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. Expectancy refers to belief that effort will result in attainment of desired performance goals, as determined by past experience, perceived self-efficacy, perceived difficulty of the performance goal, and perceived control over the goal attainment process. Instrumentality refers to belief that meeting performance expectations will be rewarded by financial incentives, recognition, promotion, or sense of accomplishment.

This belief is determined by the level of trust in those who decide on rewards, perceived control of how the reward decision is made, and understanding of the policies that connect performance and reward. Valence refers to the value put on the rewards received, or satisfaction with the rewards, which is related to factors such as needs, goals, value systems, and sources of motivation. The product term of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence is called “motivational force.” When selecting among multiple behavioral options, people will select the one with the highest amount of motivational force.3

We posit that in FBOs, personal faith is positively related to each of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. First, for expectancy, employees high in personal faith should have higher levels of meaningfulness and sense of purpose in their work, which will motivate more involvement in their work. Personal faith can also lead to greater cooperation and mutual support among coworkers. These factors will bring both higher levels of perceived self-efficacy and lower levels of goal difficulties, leading to higher expectancy. Second, instrumentality is determined by the level of trust in managers who make reward decisions. Employees and managers working in FBOs often have the same religious background, which should create greater trust because employees are likely to categorize their managers as “in-group”, rather than “out-group” and thus trust them more, according to social identity theory.21 Managers, following personal religious beliefs (e.g., honesty), are more likely to keep reward promises by honoring reward policies, which will lead to higher instrumentality. This effect should be stronger among employees high in personal faith because they are more likely to trust their managers more as mentioned above. Third, for valence in FBOs, employees high in personal faith are more likely to value rewards because they believe the rewards ultimately come from God (Psalm 16:2; James 1:17).

We further posit that in FBOs, motivation is positively related to job satisfaction. Herzberg’s two-factor theory of motivation distinguishes between motivators and hygiene factors. Motivators, such as achievement, recognition for achievement, the work itself, responsibility, and growth or advancement, lead to job satisfaction. By contrast, hygiene factors, such as job security, work conditions, and salary, do not lead to job satisfaction, but their absence can lead to dissatisfaction. As discussed, more motivated employees are likely to believe that they are able to achieve tasks and will be rewarded and recognized, which, according to two-factor theory, will lead to higher job satisfaction.4 Previous research confirms a positive relationship between intrinsic motivation (e.g., achievement, recognition) and job satisfaction in general work settings.22 Thus:

Hypothesis 2

In FBOs, motivation mediates the relationship between personal faith and job satisfaction. That is, personal faith is positively related to motivation, and motivation is positively related to job satisfaction.

PERCEIVED FIT BETWEEN PERSONAL FAITH AND ORGANIZATIONAL FAITH

Within a particular religion there is substantial diversity in beliefs and practices. This diversity makes it possible for employees in an FBO to have different levels of perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith. We posit that in FBOs, this perceived fit between personal and organizational faith is positively related to job satisfaction for two reasons. First, how workers perceive the spirituality of their organization can affect their work attitudes, beliefs, satisfaction, and capacity to overcome work challenges.23 When employees perceive a good fit between personal and organizational faith they will identify with the organization, which will make them feel more involved with the organization’s mission24 and their own job.12 These higher levels of identification and involvement should lead to higher levels of job satisfaction. Previous research confirmed the link between organizational identification and job satisfaction.25 Second, employees with a high level of perceived fit are more likely to experience a spiritual calling to their jobs when there is consistency between their own faith and that of their organization. Neubert and Halbesleben confirmed the positive link between spiritual calling and job satisfaction.15 Thus:

Hypothesis 3

In FBOs, the perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith is positively related to job

satisfaction.

We anticipated that motivation would mediate the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. First, as discussed, when employees perceive a good fit between personal and organizational faith, they will be more involved with their work and organization. The sense of spiritual calling may make them believe that they are blessed when doing the work. These factors should lead to a stronger belief that they are able to complete tasks. These employees should have high levels of expectancy. Second, a higher level of perceived fit will lead to greater perceptions that the organization will keep its promises by honoring the reward policies when employees complete tasks. These employees should have higher levels of instrumentality. Third, employees with a higher level of perceived fit may have a sense that by doing their work, they are actually glorifying God. As a result, they will put a high value on whatever rewards they receive because they are likely to believe that these rewards are not just from the organization but also from God. Their valence level will be higher. These higher levels of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence will lead to higher motivation levels.3 As discussed, more motivated employees will be more satisfied with their jobs. Thus:

Hypothesis 4

In FBOs, motivation mediates the relationship between perceived fit of personal faith and organizational faith and job satisfaction. That is, perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith is positively related to motivation, and motivation is positively related to job satisfaction.

TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP

Transformational leadership has four dimensions: idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence, or charisma, refers to the extent to which leaders behave so admirably and inspirationally that followers identify with them. Inspirational motivation refers to the extent to which leaders articulate a vision that is inspiring to their followers. Intellectual stimulation refers to the extent to which leaders challenge existing assumptions and solicit creative ideas from their followers. Individualized consideration refers to the extent to which leaders care about individual needs and listen to specific concerns.2, 26, 27

Transformational leadership has been found to impact organizations, including: subordinates’ trust in leaders,28 team members’ development of shared values with their leaders,29 moral judgment,30 perception of higher levels of core job characteristics,27 follower motivation and perceived leader effectiveness,2 and job performance.31, 32 A few studies have also examined transformational leadership’s impact in FBOs. For example, transformational leadership positively impacts affective, continuance and normative organizational commitments among faith-based university employees.33 It also affects employees’ engagement with the organization34 and emotional intelligence.35 To our knowledge, however, no study has extensively examined transformational leadership’s effects on motivation and job satisfaction in FBOs.

As proposed, in FBOs both personal faith and perceived fit are positively related to job satisfaction, mediated by motivation. Will transformational leadership have the same effect? Job characteristic theory posits that jobs should be designed with five core characteristics in mind: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, and feedback. These core characteristics produce the critical psychological states of experienced meaningfulness (the extent to which employees believe their jobs are meaningful, valued, and appreciated), experienced responsibility for the outcome (the extent to which employees feel accountable for the results of their work), and knowledge of the actual results (the extent to which employees know how well they are doing). These psychological states lead to positive outcomes, including job satisfaction.5 We suggest that transformational leadership does produce the five core job characteristics in FBOs. Specifically, leaders with inspirational motivation will communicate task significance to their employees, leaders with intellectual stimulation will nurture skill variety and autonomy, and leaders with individualized consideration will provide employees with individualized feedback, equipping them with skill variety and nurturing autonomy. These core characteristics will lead to the three psychological states, which will eventually lead to job satisfaction. Thus:

Hypothesis 5

In FBOs, transformational leadership is positively related to job satisfaction.

We further propose that motivation mediates the positive relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction. First, leaders high in inspirational motivation will bring optimistic attitudes toward goal attainment, and leaders high in intellectual stimulation will stimulate creativity among employees. Furthermore, leaders high in individualized consideration care about the specific needs of employees and listen to their concerns. All these factors should increase belief in the ability to complete assigned tasks. Thus, the expectancy dimension will be high. Second, leaders high in idealized influence are able to make employees trust and identify with them, while leaders high in individualized consideration care about their employees on an individual basis. These factors should make employees believe that leaders will honor the organization’s reward policies. Thus, the instrumentality level will be high. Third, leaders with inspirational motivation will articulate an appealing vision. In FBOs, this vision is more likely to be related to employees’ faith. As a result, employees will likely put organizational vision and benefits ahead of their own. These factors should lead employees to value the rewards given to them, whether they are extrinsic rewards (e.g., financial incentives) or intrinsic rewards (e.g., recognition). Thus, the valence level will be high. High levels of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence indicate more motivated employees who, in turn, will be more satisfied with their jobs. Thus:

We further propose that motivation mediates the positive relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction. First, leaders high in inspirational motivation will bring optimistic attitudes toward goal attainment, and leaders high in intellectual stimulation will stimulate creativity among employees. Furthermore, leaders high in individualized consideration care about the specific needs of employees and listen to their concerns. All these factors should increase belief in the ability to complete assigned tasks. Thus, the expectancy dimension will be high. Second, leaders high in idealized influence are able to make employees trust and identify with them, while leaders high in individualized consideration care about their employees on an individual basis. These factors should make employees believe that leaders will honor the organization’s reward policies. Thus, the instrumentality level will be high. Third, leaders with inspirational motivation will articulate an appealing vision. In FBOs, this vision is more likely to be related to employees’ faith. As a result, employees will likely put organizational vision and benefits ahead of their own. These factors should lead employees to value the rewards given to them, whether they are extrinsic rewards (e.g., financial incentives) or intrinsic rewards (e.g., recognition). Thus, the valence level will be high. High levels of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence indicate more motivated employees who, in turn, will be more satisfied with their jobs. Thus:

Hypothesis 6

In FBOs, motivation mediates the relationship between transformational leadership and job satisfaction. That is, transformational leadership is positively related to motivation, and motivation is positively related to job satisfaction.

Fig. 1 presents our conceptual model based on the six hypotheses.

METHODOLOGY

RESPONDENTS AND PROCEDURE

We tested the six hypotheses in a cross-sectional online survey in four Christian colleges in Canada, using an internet-based survey. All four are attached to a religious organization or tradition, have strong statements of faith and deeply embed faith in their operational structure, meeting Torry’s FBO definition.10 The link to the survey was sent to faculty and staff in each university, after permission from management. The respondents were informed that the purpose of the survey was to examine various motivational factors in FBOs. We added two screening questions to ensure that only faculty and staff (not administrators) would be included in the survey and that only employees who had been working at the university continuously for at least two years would be included (recognizing that it may take time for the three motivating factors to have an effect on job satisfaction). Questions in the survey included measures of job satisfaction, personal faith, perceived fit between personal and organizational faith, TL, motivation, demographics, and job-related questions (i.e., age, gender, education level, and years in the organization).36

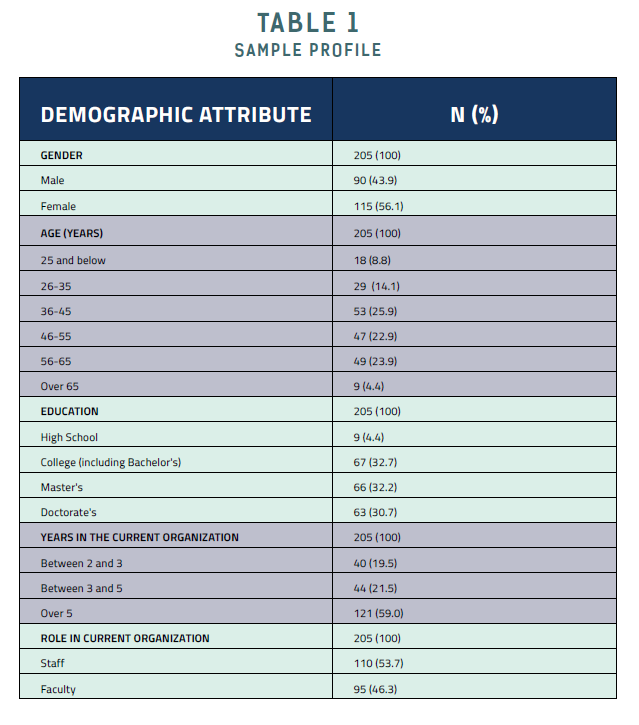

Three hundred and five respondents attempted to participate, resulting in a response rate of 43.70% (cumulatively, the four universities have 698 employees).37 We removed 98 responses because of either the two noted restrictions or missing data. We eliminated two more responses because of unengaging behaviors (too short a time to complete the survey). As a result, the final sample size was 205. As some questions asked respondents to evaluate the transformational leadership of their immediate supervisors, we anticipated there would be some unwillingness to provide accurate answers out of a concern that data would be disclosed. To overcome this possible response bias, we purposely did not ask respondents to identify their university, in addition to providing confidentiality guarantees. We were then unable to compare response patterns across the universities as well as leaving university management unexamined as an exogenous variable; however, the discrepancies in responses are likely to be low because of similar mission and organizational faith. A random drawing for three gift cards was offered as an incentive to participate. Table 1 provides the sample profile.

MEASURES

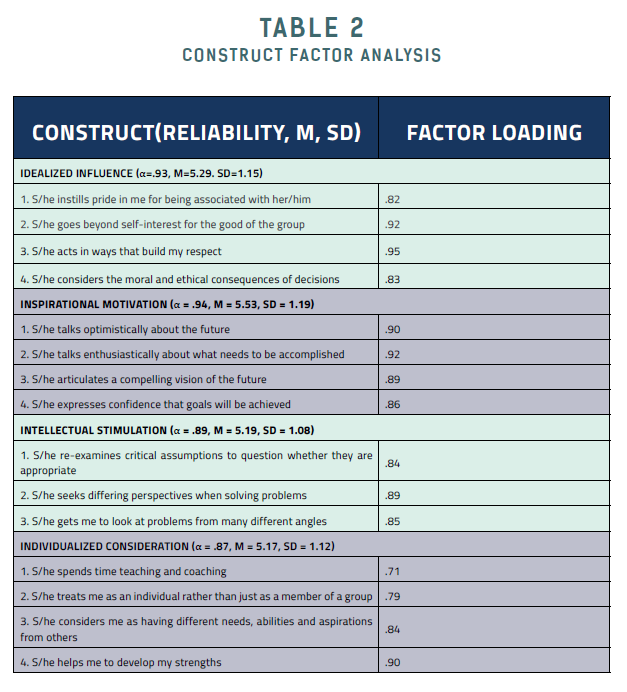

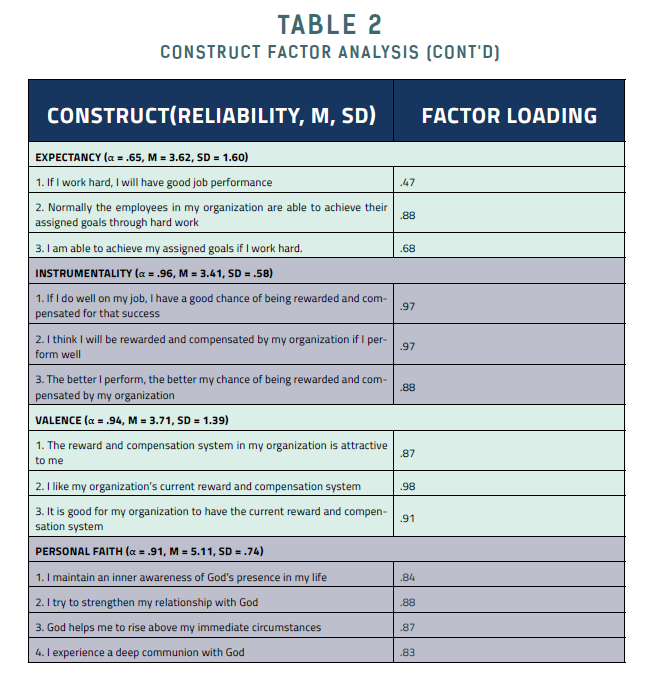

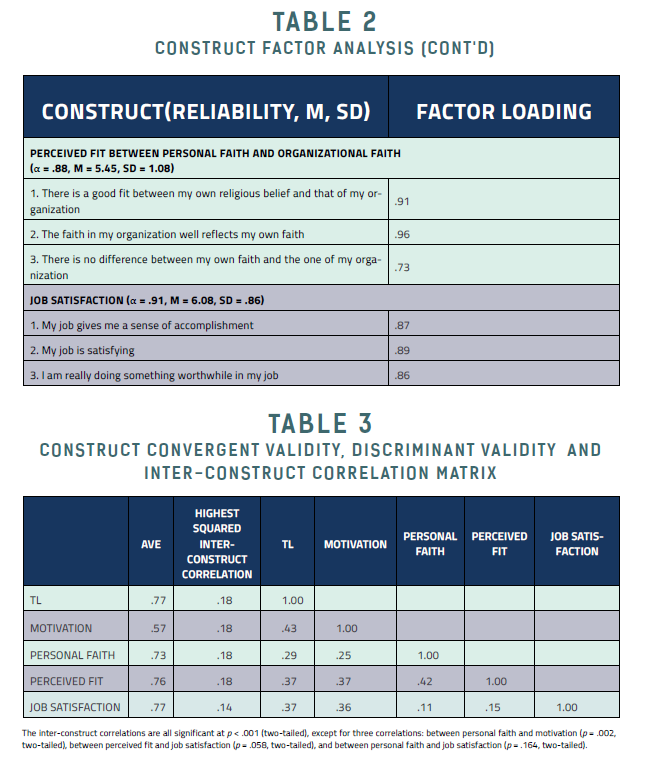

There are various schools of transformational leadership. For example, Anthony and Schwartz identify five characteristics of transformational leaders (e.g., they tend to be “insider outsiders”, and use cultural change to drive engagement). 38 Lancefield and Rangen describe four actions that transformational leaders often take (e.g., sharing leadership more systematically, and making empowerment live up to its promise).39 In this research, we adopted the 15-item seven-point scale to measure transformational leadership from Bass and Avolio’s Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire, 40 including four, four, three, and four items for idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration, respectively. The fit indexes for the four first-order factors plus one second-order factor fell within an acceptable range (χ2(86) = 240.31, p < .001; comparative fit index [CFI] = .95; Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = .94; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .09 (slightly higher than the .08 cutoff value); standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = .04), suggesting that the dimensions we used reflected the transformational leadership construct. Based on the definitions of expectancy, instrumentality, and valence, we developed four, four, and three measurement items to measure the three concepts, respectively. We dropped one item each for expectancy and instrumentality due to low factor loadings, which resulted in a nine-item seven-point scale to measure motivation, including three items each for expectancy, instrumentality, and valence. The fit indexes for the three first-order factors plus one second-order factor fell within an acceptable range (χ2(24) = 65.13, p < .001; CFI = .98; TLI = .97; RMSEA = .09 (slightly higher than the .08 cutoff value); SRMR = .06); thus, the dimensions we used reflected the motivation construct. We used a four-item seven-point scale to measure personal faith, adapted from the Spiritual Transcendence Index.41 We drafted four measurement items based on the definition of perceived fit between personal and organizational faith. We dropped one item with low factor loading, which resulted in a three-item seven-point scale to measure perceived fit. We measured job satisfaction with a three-item seven-point scale adapted from the satisfaction with overall job scale.42 All variables had good Cronbach’s alpha values. All constructs demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity. Average variance extracted from each construct ranged between .57 to .77. Table 2 provides measurement items for each construct, Cronbach’s alpha values, means, standard deviations, and factor loadings. Table 3 provides convergent and discriminant validities for each construct and inter-construct correlations.

RESULTS

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS 26 to examine the hypothesized model. We employed a second-order hierarchical model because of the multidimensional nature of transformational leadership and motivation. SEM offers a simultaneous test of an entire system of variables in a hypothesized model; as a result, it can assess the extent to which the hypothesized model is consistent with the data.43

MEASUREMENT MODEL ASSESSMENT

We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to estimate the quality of the factor structure and loadings.43 We entered the second-order variables transformational leadership and motivation (including the four dimensions of transformational leadership and the three dimensions of motivation), personal faith, perceived fit, and job satisfaction in the model. The measurement model revealed a good fit to the data (χ2(510) = 834.12, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .06; SRMR = .07), meeting the cutoff criteria when sample size is less than 250 and the number of measures is more than 30 (i.e., χ2/df < 3, expected significant p-values, CFI > .92, TLI > .92, RMSEA < .08, SRMR < .09).44 All factor loadings were equal to or greater than .68, except .47 for one item in the expectancy dimension of motivation.

COMMON METHOD VARIANCE

The cross-sectional survey research design and self-reported nature of our data could lead to the threat of common method variance (CMV). We took ex ante remedy strategies to reduce possible CMV, including assurance of anonymity and confidentiality, informing that there were no right or wrong answers, and encouraging that questions be answered honestly. We asked criterion variable questions (i.e., job satisfaction) first, followed by filler questions unrelated to this study and then predictor variables questions (i.e., personal faith, perceived fit, TL, and motivation).45 We also took ex post remedy strategies by using Gaskin and Lim’s CFA approach during data analysis to test for possible CMV.46 Specifically, we compared two CFA models, with a common latent factor added. In the first model, we set all the paths from the common latent factor to all the indicators to zero (i.e., the constrained model), while in the second model, the path coefficients are difference test revealed a significant difference between the two models (χ2 difference = 106.06, df difference = 33, p < .001; constrained model: χ2(510) = 834.12, p < .001; unconstrained model: χ2(477) = 728.06, p < .001), indicating that CMV did exist. As a result, we needed to account for the bias in the structural model. Following Gaskin and Lim’s approach, in the unconstrained CFA model, we performed data imputation, which generated adjusted scores for the five variables in the conceptual model (personal faith, perceived fit, TL, motivation, and job satisfaction). STRUCTURAL MODEL ASSESSMENT

STRUCTURAL MODEL ASSESSMENT

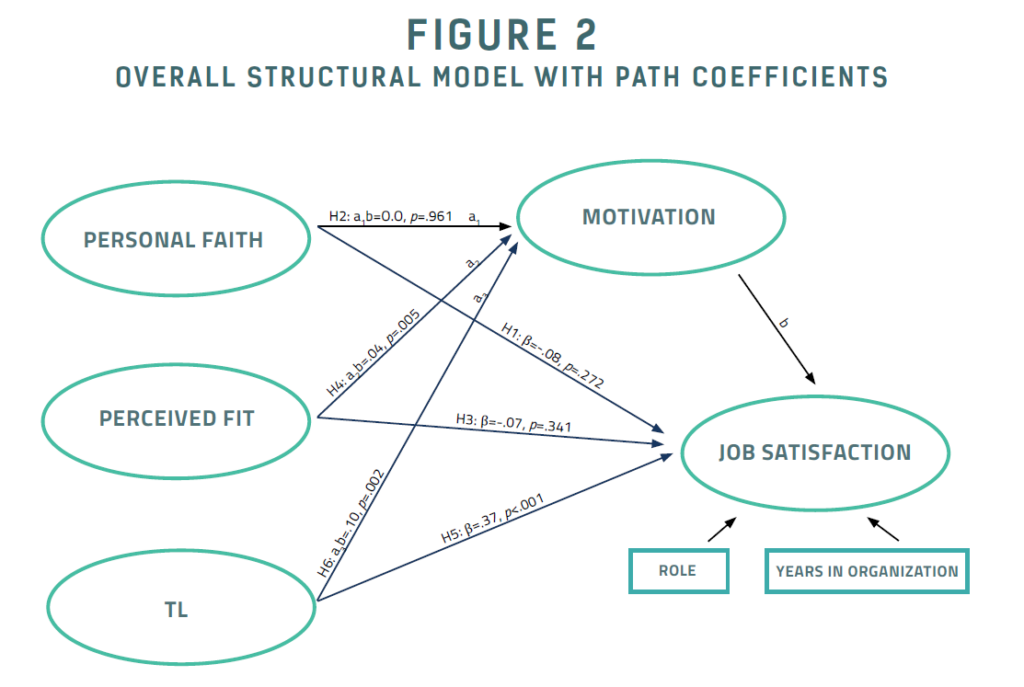

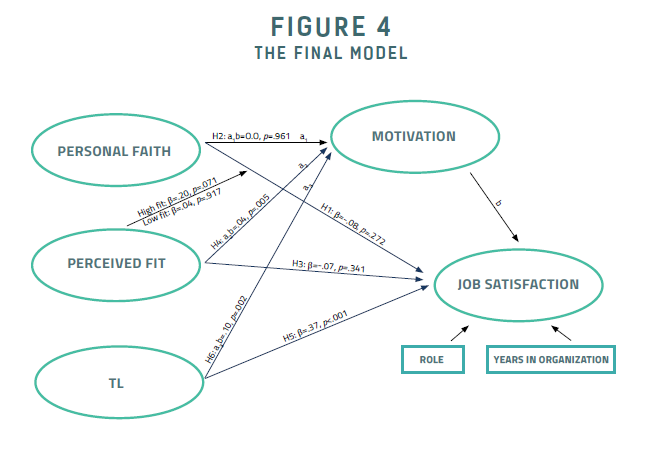

We performed SEM to determine whether the data collected support for the six hypotheses.43 Iacobucci posits that SEM models perform well even with small samples (e.g., 50 to 100).47 Bentler and Chou (1987) propose a rule of thumb that the ratio of sample size to number of free parameters should be higher than 5:1 in order to get trustworthy parameter estimates.48 A sample size of 205 and 26 free parameters in our SEM model resulted in a ratio of 7.9:1, higher than the 5:1 threshold ratio. In the structural model, in addition to the five variables in the conceptual model (now with adjusted scores), we added role (faculty and staff) and years in the organization as control variables. We did not include gender, age, and education level as controls, because previous research shows that these variables are not related to job satisfaction.49 The results indicated that the hypothesized model fit the data well (χ2(2) = 3.19, p = .203; CFI = .99; TLI = .94; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .02) (Hair et al.).44 Fig. 2 presents the overall structural model with path coefficients. The results show that neither personal faith (β = –.08, p = .272) nor the perceived fit between personal and organizational faith (β = –.07, p = .341) affects job satisfaction, thus rejecting H1 and H3, respectively; however, transformational leadership is positively related to job satisfaction (β = .37, p < .001), in support of H5. Mediation effects were tested using Preacher and Hayes (2004) bootstrapping method. This method provides point estimates and confidence intervals, with which one can assess whether a mediation effect exists. Point estimate indicates the mean over the number of bootstrapped samples. If zero does not fall between the resulting confidence interval, it can be concluded that there is a significant mediation effect. 50 The results indicate that motivation has no mediating effect on the link between personal faith and job satisfaction (a1b = .00, 95% confidence interval [CI] = [–.04, .04], p = .961), thus rejecting H2; however, motivation mediates both the link between perceived fit of personal and organizational faith and job satisfaction (a2b = .04, 95% CI = [.01, .08], p = .005) and the link between transformational leadership and job satisfaction (a3b = .10, 95% CI = [.05, .18], p = .002), in support of H4 and H6, respectively. Neither role nor years in the organization affect job satisfaction (ps > .05).

DISCUSSION

We found that in FBOs, (1) personal faith has no effect on either motivation or job satisfaction, (2) perceived fit has no direct effect on job satisfaction but has an indirect effect through the full mediation of motivation, and (3) transformational leadership has direct effect on job satisfaction and indirect effect through the mediation of motivation.

Contrary to our hypotheses, personal faith was not related to either motivation (β = .00, p = .999) or job satisfaction. At a cursory glance, this finding is difficult to understand and counterintuitive; however, it becomes more understandable when we consider the positive relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. Among employees with higher perceived fit levels, a higher personal faith level may lead to greater perceived meaningfulness of their work and identification with the organization, which in turn will lead to higher levels of motivation and job satisfaction. By contrast, employees with lower perceived fit levels are more likely to disagree with the organization’s faith, perceive less freedom to discuss their own faith at work, lack meaningfulness in work, and not identify with the organization. All these factors could diminish job satisfaction. It is possible that among employees with low perceived fit levels, the higher their personal faith the lower the job satisfaction, because employees high in personal faith are then more likely to disagree with the organizational faith. Consequently, in a group of employees, high levels of job satisfaction from those with high personal faith and perceived fit may be balanced out by low levels of job satisfaction from those with high personal faith but low perceived fit.

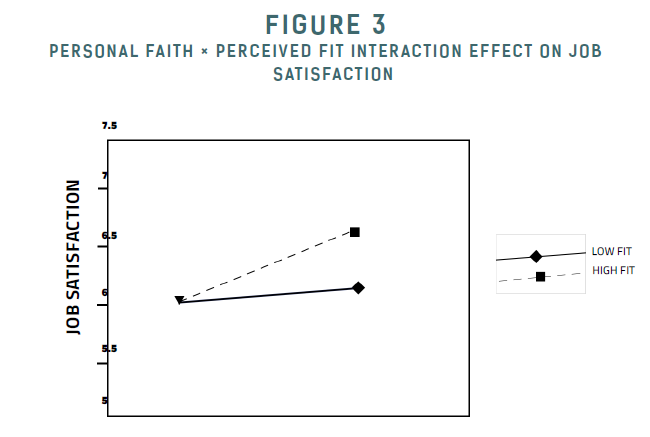

We ran a forward stepwise regression (with two models) to test this speculation. In the first model, personal faith and perceived fit were the independent variables and job satisfaction the dependent variable. In the second model, we added the interaction between personal faith and perceived fit as one more independent variable. We standardized all the independent variables in the models to reduce potential multicollinearity between the interaction term and their components.51 The results indicated that the first model was not significant (p = .107) while the second was marginally significant (p = .063). Thus, we selected the second model as the final model, in which the interaction between personal faith and perceived fit has a marginally significant effect (β = –.08, p = .092) but neither personal faith (p = .160) nor perceived fit (p = .115) has a main effect. The highest variance inflation factor was only 1.95.44 To further examine the personal faith variation within high or low perceived fit situations, we ran simple slope tests at one standard deviation below and above the mean of perceived fit, respectively. The results showed that among employees low in perceived fit, the effect of personal faith on job satisfaction was not significant (β = .04, p = .917). Conversely, among employees high in perceived fit, personal faith has a marginally significant and positive effect on job satisfaction (β = .20, p = .071). This interaction pattern indicates that the effect of personal faith on job satisfaction only exists among employees high in perceived fit, thus confirming our speculation. This result also explains why personal faith has no significant main effect on job satisfaction among all employees (both high and low on perceived fit). Fig. 3 presents a plot of the personal faith × perceived fit interaction effect. Fig. 4 presents the final model, depicting all the findings in this research.

Another finding differing from our expectations is that perceived fit was not related to job satisfaction. However, as hypothesized, motivation mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. These two findings together indicate that motivation fully mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. That is, if motivation were not included in the model as the mediator, perceived fit should have been significantly related to job satisfaction (a correlation analysis confirmed that the two variables are indeed correlated; r = .14, p = .039); however, when motivation is inserted, the significant relationship disappears. The full mediation indicates that when employees in FBOs perceive a higher level of fit between their faith and that of the organization, they will be more motivated, leading to higher job satisfaction. Furthermore, as analyzed, perceived fit is a condition for personal faith to have an effect on job satisfaction. Only when employees with strong religious beliefs and practices believe that their faith matches that of their organization are they likely to be more satisfied with their jobs.

Another finding differing from our expectations is that perceived fit was not related to job satisfaction. However, as hypothesized, motivation mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. These two findings together indicate that motivation fully mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. That is, if motivation were not included in the model as the mediator, perceived fit should have been significantly related to job satisfaction (a correlation analysis confirmed that the two variables are indeed correlated; r = .14, p = .039); however, when motivation is inserted, the significant relationship disappears. The full mediation indicates that when employees in FBOs perceive a higher level of fit between their faith and that of the organization, they will be more motivated, leading to higher job satisfaction. Furthermore, as analyzed, perceived fit is a condition for personal faith to have an effect on job satisfaction. Only when employees with strong religious beliefs and practices believe that their faith matches that of their organization are they likely to be more satisfied with their jobs.

As hypothesized, transformational leadership is positively related to job satisfaction in FBOs, and this link is mediated by motivation. This finding indicates that the transformational leadership practices that are effective in secular organizations, such as being charismatic, articulating a vision, soliciting creative ideas, and taking individual care of each follower,2 are also effective in motivating employees in FBOs. In other words, whether working for God or not, these transformational leadership practices are effective. Furthermore, the higher path coefficient from transformational leadership to motivation (β = .45, p < .001) than that from perceived fit to motivation (β = .20, p = .003) indicates that transformational leadership may be even more effective than perceived fit in motivating employees in FBOs. Furthermore, the finding that transformational leadership has both a direct effect on job satisfaction and an indirect effect through motivation indicates that transformational leadership practices will motivate employees, which in turn will lead to job satisfaction, and that motivation only partially mediates transformational 2leadership’s effect on job satisfaction. That is, in addition to motivation, there should be other mediators in the link between transformational leadership and job satisfaction in FBOs. These transformational leadership related findings are particularly inspiring because they indicate the necessity to explore the possible effects of other management practices and leadership styles in faith-based work environments. Other practices effective in secular organizations may be just as effective in FBOs. Exploring such endeavors would advance the literature on both leadership and FBOs. Finally, we find that neither role nor years in the organization have an effect on job satisfaction. These findings suggest there may be limited need to differentiate between roles when developing motivational strategies in FBOs, and longer service does not necessarily lead to higher job satisfaction.

THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTIONS

This research makes five theoretical contributions. First, we advance the transformational leadership literature by empirically confirming that transformational leadership is effective in FBOs. Specifically, we confirm that transformational leadership leads to more motivated employees, which in turn results in higher job satisfaction. Given that employees in FBOs put God ahead of a human leader we questioned if this would reduce transformational leadership’s effectiveness. However, our results indicate that transformational leadership was effective in FBOs. Furthermore, the partial mediation of motivation found in our research indicates that the mediating mechanism in the link between transformational leadership and job satisfaction in FBOs is complex; other variables have a mediating effect in this relationship as well.

Second, we advance the motivation literature by empirically confirming that expectancy theory is applicable in faith-based work environments. Our results show that both transformational leadership and perceived fit have positive effects on motivation and that motivation positively affects job satisfaction (β = .25, p < .001). Specifically, both transformational leadership practices and perceived fit will lead to employees’ stronger beliefs that they are able to complete assigned tasks (expectancy), that managers will honor the reward policies (instrumentality), and that they value the rewards given to them (valence). These factors will make employees more satisfied with their jobs. Given that rewards and compensation included both non-financial (e.g., recognition, promotion) and financial (e.g., pay increase, commissions) incentives, the findings further indicate that even if employees in FBOs have the religious belief that they should not focus on personal gain, financial incentives are still effective motivators leading to job satisfaction. A possible explanation for this seeming contradiction is that employees may view the rewards as God’s recognition for their work. We did not examine this speculation in the study, but leave it to future research to explore empirically.

Third, we introduce the construct of perceived fit between personal faith and organizational faith and find that it positively affects motivation and job satisfaction and moderates the relationship between personal faith and job satisfaction (that is, personal faith affects job satisfaction only among employees high on perceived fit, but not among employees low on perceived fit). In addition, motivation fully mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. This finding provides a clear picture of the underlying mechanism in the link between perceived fit and job satisfaction.

Fourth, although research has examined personal faith in general work settings,12 to our knowledge, our study is the first to explore the effect of personal faith on job satisfaction in FBOs. We find that this relationship is more complex than expected. When not differentiating employees by high and low perceived fit levels, personal faith was not related to job satisfaction in FBOs. However, when we add perceived fit as a moderator, the picture became clearer: personal faith indeed positively affects job satisfaction in FBOs, but only when employees perceive their faith as matching that of their organization. When employees do not perceive such a match, the relationship between personal faith and job satisfaction disappears.

Fifth, we show that in addition to expectancy theory of motivation, the other two motivation theories used in this research, two-factor theory4 and job characteristic theory,5 are applicable in FBOs as well. We empirically confirm the two relationships (between motivation and job satisfaction, and between transformational leadership and job satisfaction) as we hypothesized.

MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Motivating employees in FBOs has been explored in some ways. For example, through Employee Engagement Survey and 360 Leadership Review, the Best Christian Workplaces Institute helps Christian organizations improve their effectiveness.52 Based on our research we would make three key recommendations to further assist management in FBOs. First, transformational leadership works in FBOs and when hiring managers, FBOs should select applicants with strong transformational leadership traits. In daily operations, FBOs should also encourage and promote transformational leadership practices among managers through training and performance evaluations. These practices will lead to higher motivation and job satisfaction. Second, when hiring employees, FBOs should consider not only whether an applicant has strong personal faith within a broader type of religion but also whether there is a perceived fit between personal faith and that of the organization. Furthermore, after employees are hired, organizations should offer training and communications in the faith of the organization for the purpose of increasing the perceived fit levels. These procedures are important because our results show that perceived fit, but not personal faith, positively affects employees’ levels of motivation and job satisfaction. In addition, these training and communication programs should be helpful in fulfilling the organization’s mission, which ultimately is to glorify God.53 Third, in addition to transformational leadership practices and perceived fit, if FBOs find out that other factors or policies are effective to motivate employees, they should promote them because our results show that motivated employees in FBOs are more satisfied with their jobs.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This paper has several limitations that we plan to address in future research. First, we surveyed only faculty and staff in four Christian colleges. In addition, we only examined the role and years in the university, not whether employees in different disciplines have specific response patterns. We also did not examine other types of FBOs affiliated with other religions, or FBOs in other countries, and question whether the motivational factors we examined would have different effects in those circumstances. We also did not examine commercial companies with Christian leadership and mission which may have some similarity to FBOs. A much broader future study will determine the generalizability of our findings.

Second, we did not explore the effects of other possible motivating factors in FBOs (e.g., servant leadership, transactional leadership). For example, personal commitment to serving God may in itself motivate employees in FBOs.54 Erisman and Daniels also find that many corporate job performance appraisals tend indirectly to measure Christian scriptural values (e.g., faithfulness),55 which should provide motivational incentives for employees even in non-FBOs. While not the focus of our research, management in Christian organizations may be able to motivate by simply highlighting the alignment of these scriptural values with employees’ personal faith. We also did not examine the possible effects of the three motivating factors on other attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (e.g., organizational identification, organizational citizenship behavior, turnover intention, organizational commitment, job performance). These issues were beyond the scope of this study and future research is needed to determine the overall motivating mechanisms in faith-based work settings.

Third, although we took ex ante remedies in our questionnaire design, our data analysis shows that some CMV existed. We note that as an ex post remedy we performed data imputation,46 before analyzing the structural model.

Fourth, in our model we did not test the possible relationship between transformational leadership and perceived fit between personal and organizational faith. However, transformational leaders may be able to improve their employees’ perceived fit level with inspirational motivation activities such as articulating a faith-based vision that is appealing and inspiring. Finally, in our model we proposed, and empirically verified, that motivation mediates the relationship between perceived fit and job satisfaction. However, it is also possible that perceived fit mediates the relationship between motivation and job satisfaction and this warrants future exploration.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

RONNIE CHUANG-RANG GAO is Associate Professor of Marketing in the School of Business, Trinity Western University in Langley, British Columbia, Canada. Ronnie’s research focuses on several different areas including cross-(sub)cultural consumer behavior, sales management, and green consumer behavior. His work has been published in Journal of Business Research, Association for Consumer Research (ACR) North American Advances, and American Marketing Association (AMA) Proceedings. Ronnie holds a B.Eng. in Electrical Engineering from Tongji University in Shanghai, China, an M.B.A. from the University of British Columbia, and a Ph.D. in Business Administration from Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

KEVIN SAWATSKY is Dean and Professor of Law in the School of Business at Trinity Western University, Langley, British Columbia, Canada. Kevin has been a lawyer in B.C. for twenty-nine years with a focus on charities law, thus having acquired a deep understanding of charitable organizations. He has researched and written about charitable organizations with a particular focus on human rights law and faith-based organizations. Kevin holds a Juris Doctor degree from the University of Victoria, an MBA from the University of British Columbia, and a Bachelor of Commerce degree also from UBC.

NOTES

1 Ellwood, Robert S. The Encyclopedia of World Religions. New York: Infobase Publishing (2008).

2 Judge, Timothy A., and Ronald F. Piccolo. “Transformational and Transactional Leadership: A Meta-Analytic Test of Their Relative Validity.” Journal of applied psychology 89, no. 5 (2004): 755-768.

3 Vroom, Victor H. Work and Motivation. Oxford, England: Wiley, 1964.

4 Herzberg, Frederick. “One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees.” Harvard Business Review Boston, MA, 1968.

5 Hackman, J. Richard, and Greg R. Oldham. “Motivation through the Design of Work: Test of a Theory.” Organizational behavior and human performance 16, no. 2 (1976): 250-79.

6 Bradley, Tamsin. “A Call for Clarification and Critical Analysis of the Work of Faith-Based Development Organizations (Fbdo).” Progress in Development Studies 9, no. 2 (2009): 101-14.

7 Bielefeld, Wolfgang, and William Suhs Cleveland. “Defining Faith- Based Organizations and Understanding Them through Research.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 42, no. 3 (2013): 442-67.

8 Clarke, Gerard. “Faith Matters: Faith-Based Organisations [sic], Civil Society and International Development.” https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1317. Journal of International Development 18, no. 6 (2006): 835-https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1317.

9 Smith, Steven Rathgeb, and Michael R. Sosin. “The Varieties of Faith Related Agencies.” Public Administration Review 61, no. 6 (2001): 651-70.

10 Torry, Malcolm. “Managing Faith-Based and Mission Organizations.” In Managing Religion: The Management of Christian Religious and Faith-Based Organizations, 50-86. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

11 Werner, Andrea. “The Influence of Christian Identity on Sme Owner–Managers’ Conceptualisations of Business Practice.” Journal of Business Ethics 82, no. 2 (2008): 449-462. https://doi.org/10.1007/ s10551-008-9896-8.

12 Kutcher, Eugene J., Jennifer D. Bragger, Ofelia Rodriguez-Srednicki, and Jamie L. Masco. “The Role of Religiosity in Stress, Job Attitudes, and Organizational Citizenship Behavior.” Journal of Business Ethics 95, no. 2 (2010): 319-37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551- 009-0362-z.

13 Rosso, Brent D., Kathryn H. Dekas, and Amy Wrzesniewski. “On the Meaning of Work: A Theoretical Integration and Review.” Research in Organizational Behavior 30 (2010): 91-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001.

14 Fernando, Mario, and Brad Jackson. “The Influence of Reli- gion-Based Workplace Spirituality on Business Leaders’ Decision-Making: An Inter-Faith Study.” Journal of Management & Organization 12, no. 1 (2006): 23-39. https://doi.org/10.5172/ jmo.2006.12.1.23.

15 Neubert, Mitchell J., and Katie Halbesleben. “Called to Commitment: An Examination of Relationships between Spiritual Calling, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment.” Journal of Business Ethics 132, no. 4 (2015): 859-72.

16 Ashmos, Donde P., and Dennis Duchon. “Spirituality at Work: A Conceptualization and Measure.” Journal of management inquiry 9, no. 2 (2000): 134-45.

17 Locke, Edwin A. “The Nature and Causes of Job Satisfaction.” Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (1976).

18 Judge, Timothy A., Ronald F. Piccolo, Nathan P. Podsakoff, John Shaw, and Bruce L. Rich. “The Relationship between Pay and Job Satisfaction: A Meta-Analysis of the Literature.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 77, no. 2 (2010): 157-67. https://doi.org/https://doi. org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.002.

19 Milliman, John, Andrew J. Czaplewski, and Jeffery Ferguson. “Workplace Spirituality and Employee Work Attitudes: An Exploratory Empirical Assessment.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 16, no. 4 (2003): 426-47. https://doi. org/10.1108/09534810310484172.

20 Linge, Teresia Kavoo, and Janet Mutinda. “Extrinsic Factors That Affect Employee Job Satisfaction in Faith Based Organizations.” Journal of Language, Technology & Entrepreneurship in Africa 6, no. 1 (2015): 72-81.

21 Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. C. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall (1986).

22 Stringer, Carolyn, Jeni Didham, and Paul Theivananthampillai. “Motivation, Pay Satisfaction, and Job Satisfaction of Front Line Employees.” Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management 8, no. 2 (2011): 161-79. https://doi.org/10.1108/11766091111137564.

23 Giacalone, Robert A., and Carole L. Jurkiewicz. “Right from Wrong: The Influence of Spirituality on Perceptions of Unethical Business Activities.” Journal of Business Ethics 46, no. 1 (2003): 85-97. https:// doi.org/10.1023/A:1024767511458.

24 Cable, Daniel M., and D. Scott DeRun. “The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Subjective Fit Perceptions.” Journal of Applied Psychology 87, no. 5 (2002): 875-84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875.

25 Karanika-Murray, M., Duncan, N., Pontes, H.M. and Griffiths, M.D. “Organizational identification, work engagement, and job satisfaction.” Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30 no. 8 (2015): 1019-33.

26 Bass, Bernard M. Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: The Free Press, 1985.

27 Piccolo, Ronald F., and Jason A. Colquitt. “Transformational Lead- ership and Job Behaviors: The Mediating Role of Core Job Characteristics.” Academy of Management journal 49, no. 2 (2006): 327-40.

28 Dirks, Kurt T., and Donald L. Ferrin. “Trust in Leadership: Meta-Analytic Findings and Implications for Research and Practice.” Journal of applied psychology 87, no. 4 (2002): 611-628.

29 Gillespie, Nicole A., and Leon Mann. “Transformational Leadership and Shared Values: The Building Blocks of Trust.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 19, no. 6 (2004): 588-607.

30 Schwepker, Charles H., and David J. Good. “Improving Salespeople’s Trust in the Organization, Moral Judgment and Performance through Transformational Leadership.” Journal of Business & Indus- trial Marketing 28, no. 7 (2013/08/19 2013): 535-46. https://doi. org/10.1108/JBIM-06-2011-0077.

31 Gao, Ronnie (Chuang Rang), William H. Murphy, and Rolph E. Anderson. “Transformational Leadership Effects on Salespeople’s Attitudes, Striving, and Performance.” Journal of Business Research 110 (2020/03/01/ 2020): 237-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbus-res.2020.01.023.

32 Wang, Gang, In-Sue Oh, Stephen H. Courtright, and Amy E. Colbert. “Transformational Leadership and Performance across Criteria and Levels: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Research.” Group & organization management 36, no. 2 (2011): 223-70.

33 Maiocco, Kimberly Ann. “A Quantitative Examination of the Relationship between Leadership and Organizational Commitment in Employees of Faith-Based Organizations.” Liberty University, 2017. 34 Reynolds, Lisa M. A Study of the Relationship between Associate Engagement and Transformational Leadership in a Large, Faith-Based Health System. Our Lady of the Lake University, 2008.

35 Meredith, Cheryl L. The Relationship of Emotional Intelligence and Transformational Leadership Behavior in Non-Profit Executive Leaders. Capella University, 2008.

36 We did not measure respondents’ ethnicity out of a concern about possible identification of respondents raised by the Research Ethics Board at the authors’ university because of the small size of all four universities.

37 Out of identification concerns, we report the cumulative number rather than the workforce size for each university.

38 Anthony, Scott D. and Evan I. Schwartz. “What the Best Transformational Leaderships Do.” Harvard Business Review (2017). https:// hbr.org/2017/05/what-the-best-transformational-leaders-do (retrieved June 13, 2022)

39 Lancefield, David and Christian Rangen. “4 Actions Transforma- tional Leaders Take.” Harvard Business Review (2021). https://hbr. org/2021/05/4-actions-transformational-leaders-take (retrieved June 13, 2022)

40 Bass, Bernard M, and Bruce J Avolio. Mlq Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire . Redwood City. Ca: Mind Garden. 1995.

41 Seidlitz, Larry, Alexis D. Abernethy, Paul R. Duberstein, James S. Evinger, Theresa H. Chang, and Bar’bara L. Lewis. “Development of the Spiritual Transcendence Index.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41, no. 3 (2002): 439-53. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00129.

42 Rutherford, Brian, James Boles, G. Alexander Hamwi, Ramana Madupalli, and Leann Rutherford. “The Role of the Seven Dimensions of Job Satisfaction in Salesperson’s Attitudes and Behaviors.” Journal of Business Research 62, no. 11 (2009): 1146-51.

43 Byrne, Barbara M. . “Structural Equation Modeling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming.” London: Lawrence Erlbaum Association–Publisher, 2001.

44 Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. Multivariate Data Analysis. UK: Pearson Education Limited, 2014.

45 Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. “From the Editors: Common Method Variance in International Business Research.” Journal of International Business Studies 41, no. 2 (2010): 178-84. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88.

46 Gaskin, James and Lim, J. (2017). CFA Tool. AMOS Plugin.

47 Iacobucci, D. “Structural equations modeling: Fit Indices, sample size, and advanced topics.” Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20 no.1 (2010): 90-98.

48 Bentler, P.M. and Chou, C.P. “Practical issues in structural modeling.” Sociological Methods & Research, 16 no. 1 (1987): 78-117.

49 Walker, Alan G. “The Relationship between the Integration of Faith and Work with Life and Job Outcomes.” Journal of Business Ethics 112, no. 3 (2013): 453-61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1271-0.

50 Preacher, K.J., and Hayes, A.F. “SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models.” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36 (2004): 717–731.

51 Aiken, Leona S, and Stephen G West. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage Publications, Incorporated, 1991.

52 Best Christian Workplaces Institute. https://www.bcwinstitute. org/360-review/ (Retrieved June 9, 2022)

53 We thank an anonymous reviewer for offering this insight.

54 We thank an anonymous reviewer for offering this insight.

55 Erisman, Al and Denise Daniels. “The Fruit of the Spirit: Application to Performance Management.” Christian Business Review, No. 2 (2013): 27-34.