Renaissance of the Bible was an exhibit in 2016 on the 500th anniversary of Erasmus’ first printed Greek text. Some of the lectures from the special conference also held that year, Ad Fontes, Ad Futura: Erasmus’ Bible and the Impact of Scripture, can be found online.

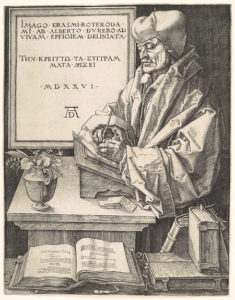

Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) was part of the Renaissance movement back to the classical sources of knowledge. Wanting to revitalize the Church, Erasmus believed all Christians should have their lives transformed through the true “philosophy of Christ.” He dedicated his life to the study and publishing of the Bible and the writings from the earliest centuries of the Church. Erasmus was recognized throughout Europe as the greatest shoolar of his day. The focus of his study was the Bible.

Foundations in Youth

Born in 1466, in Rotterdam, this illegitimate son of a priest and his concubine was named after St. Erasmus. After both parents died of the plague, Erasmus was sent to St. Lebuin’s Latin school in Deventer from the age of 8 to 15. Here Erasmus learned of Devotio Moderna, a movement of religious reform focusing on apostolic simplicity, separation from the sinful world, and Christ as the great example of obedience. Poverty led Erasmus to enter the Augustinian monastery at Steyn in 1487. He took monastic vows in1488, and was ordained a priest in 1492.

De Imitatione Christi by Thomas a Kempis (c.1380-1471). Venice, 1677

De Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ), first printed in 1471, is the most translated Christian book after the Bible. Thomas à Kempis attended the same Latin school in Deventer later attended by Erasmus. There he learned and became part of the Devotio Moderna, a movement for religious reform and pious life through humility, obedience, and a simple life. Kempis’ meditations on the life and teachings of Jesus were designed to develop the interior life of the Christian soul.

Biblical and Textual Scholar

Erasmus was allowed to leave the monastery and pursue studies at the University of Paris. In 1496, he took the name Desiderius, the Latin translation of the Greek name Erasmus, both meaning “Beloved.” In 1499, Erasmus went to England, and there his study of the Scriptures deepened. At Oxford he met John Colet (c. 1478-1535), later to be Dean of St. Paul’s in London. Colet was lecturing at Oxford on the epistles of St. Paul. He favored a historical, grammatical interpretation of Scripture rather than the allegorical, mystical interpretations favored by the medieval Scholastics. With Colet’s encouragement, Erasmus began an intensive study of Greek while writing what became a 4 volume commentary on St. Paul’s epistle to the Romans, published in 1502.

In 1504, while at a monastery at Louvain, Erasmus discovered a manuscript by Lorenzo Valla (1407-1457) – Adnotationis Novum Testamentum. Valla had made a verse by verse comparison of the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, which dominated the middle ages, with Greek biblical manuscripts, noting the variants. Many criticized Valla for seeming to tamper with the venerated Latin Vulgate Bible, but Valla was going back to the source, the Greek biblical text, to establish the authenticity of the biblical text, an early venture into textual criticism. The discovery of Valla’s manuscript encouraged Erasmus in his biblical studies.

In 1505, Erasmus printed Valla’s Adnotationis Novum Testamentum. In his preface, Erasmus wrote of the importance of recovering true spirituality by recovering the true text of the Bible. At this time, he also began a Latin translation of the New Testament from the Greek, correcting errors in the Latin Vulgate used throughout the western Church for a thousand years.

Philosophy of Christ

Erasmus believed the Church with its corruption and deadness could be spiritually reformed by a return to its roots in the Bible, as understood by the biblical commentaries of the early church fathers. He published important editions of works by the fathers of the early church, including Jerome, Chrysostom, Origin, Irenaeus, Ambrose, Augustine, and Basil. In contrast with medieval scholastic philosophy based on Aristotelian logic, which only the educated could comprehend, Erasmus believed the philosophy of Christ was for all. He published many Biblical works:

- A Greek New Testament with Latin translation,

- Editions of biblical commentaries of the Church fathers,

- a Method of Theology.

All were meant to revive the philosophy of Christ, a knowledge of Christ which transformed the way one lived.Erasmus wrote that “The most exalted aim in the revival of philosophical studies will be to obtain a knowledge of the pure and simple Christianity of the Bible.” (From Ad Servitium, as quoted by Jean D’Aubigne, History of the Reformation of the Sixteenth Century, volume 1. New York: Robert Carter & Brothers, 1853, 124) Erasmus was working on his edition of the works of St. Jerome while also working on his translation of the Greek New Testament into Latin. Like Jerome,

Erasmus was eloquent, a great linguist, and knowledgeable in the classics and in history. Both men had a kind of conversion from classical literature to sacred letters.

Froben: Printer and Friend

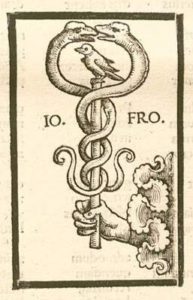

About 1491, fifty years after Gutenberg printed the Bible, Johann Froben (c. 1460-1527) established a printing house in Basel, Switzerland which gained a European reputation. Johann Froben’s shop sign was painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, who provided the illustrations and designs for many of Froben’s books. The printer’s device was also used in Froben publications since 1517. The design refers to Matthew 10:16, “Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves; be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.”

About 1491, fifty years after Gutenberg printed the Bible, Johann Froben (c. 1460-1527) established a printing house in Basel, Switzerland which gained a European reputation. Johann Froben’s shop sign was painted by Hans Holbein the Younger, who provided the illustrations and designs for many of Froben’s books. The printer’s device was also used in Froben publications since 1517. The design refers to Matthew 10:16, “Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves; be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves.”

A New Instrument

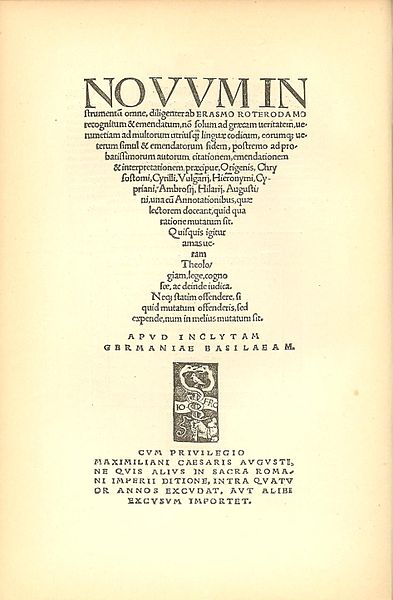

Erasmus called his Greek and Latin New Testament Novum Instrumentum. He believed this Greek text with his new Latin translation was indeed a new instrument for the revival of Christian spirituality, going back to the biblical source of the faith.

Early church fathers Tertullian, Augustine, and Jerome had also called the Christian Scriptures an “Instrument.” Erasmus noted that a person leaving a will would make an oral testament, or statement of intent. The written document itself would be the “instrumentum.” Jesus made the oral statement to the disciples; when it was written down it became an instrument. No one accepted Erasmus’ reasoning, and future editions used the standard wording “Novum Testamentum.”

Novum Instrumentum, 1st edition. Desiderius Erasmus. Basel: Johan Froben, 1516.

Erasmus’s printing of the first Greek New Testament included his Latin translation of the text, which showed some of the weaknesses of the Latin Vulgate translation, the Bible of the church for over 1000 years. Erasmus dedicated this New Testament to Pope Leo X, knowing that having the Pope’s approval would possibly deflect his critics. Novum Instrumentum also included

- Paraclesis – an encouragement to read the new Testament

- Methodus – pointers on how to read the New Testament

- Apologia – a defense of the printing of the New Testament in the new Latin translation.

The hour glass shaped title at the smallest portion focuses on the phrase meaning “If you love true theology, read this, understand it, and then pass judgment.” Erasmus was challenging scholars to compare the Greek and his new Latin translation before defending the traditional Latin Vulgate Bible. In his preface to the 1516 Greek/Latin New Testament, Erasmus wrote:

We preserve the letters written by a dear friend, we kiss them fondly, carry them about, we read them again and again, yet there are many thousands of Christians who, although they are learned in other respects, never read, however, the evangelical and apostolic books in an entire lifetime…these writings bring you the living image of His [Christ’s] holy mind and the speaking, healing, dying, rising Christ himself, and thus they render Him so fully present that you would see less if you gazed upon Him with your very eyes.

In his Latin translation printed parallel to the Greek text, Erasmus sought to correct errors in the Latin Vulgate translation the church had used for 1000 years. The Church protested many of these changes, since they affected church doctrines:

-

- Matthew 3:2, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.” Erasmus translated the Greek word “metanoiete” with the Latin “respiscite”, meaning “a change of mind,” a translation first encouraged by Lorenzo de Valla. The Latin Vulgate translated this “penitentiam agite,” or “do penance,” and the practice of doing penance came to support the Catholic sacramental system.

- Luke 1:28, The Vulgate translates Gabriel’s greetings to Mary as “full of grace,” which the Church interpreted as a reservoir of grace to be dispensed to others. Erasmus correctly translated the greeting as “favored one.”

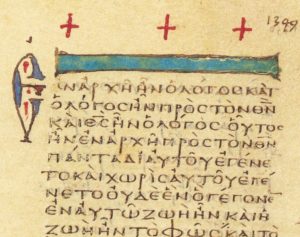

- John 1:1, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” Erasmus translated the Greek word “logos” into the Latin “sermo” rather than the Vulgate’s “verbum” or word. Erasmus thought “sermo” better conveyed the idea of rational discourse implicit in the Greek word “logos.”

- Ephesians 5:32, “This mystery is profound, and I am saying that it refers to Christ and the church.” Erasmus translated the Greek word “mysterium” as mystery; the Latin Vulgate translated it as “sacramentum,” which reinforced the formal sacramentalism of the Roman Church.

Erasmus dedicated his Novum Instrumentum to Pope Leo. In his dedication, Erasmus wrote,

I perceived that that teaching which is our salvation was to be had in a much purer and more lively form if sought at the fountain-head and drawn from the actual sources than from pools and runnels. And so I have revised the whole New Testament (as they call it) against the standard of the Greek original.

By dedicating his Greek text and Latin translation to Pope Leo, Erasmus was trying to forestall criticism of his work. Pope Leo wrote Erasmus a very complimentary letter which he included in his second edition.

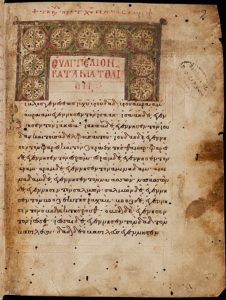

Though Erasmus had worked with Greek manuscripts in England, such as the Leicester Codex, in preparing his Greek text for printing, he used seven manuscripts borrowed from the Dominican Library at Basel and from Johannes Reuchlin, none any earlier than the twelfth century. The manuscript Erasmus had of Revelation was incomplete, so he translated the Vulgate into Greek to fill in the gaps! (He did tell his readers in a footnote that he had done this).

Critics of Erasmus’ new Latin translation of the Greek text noted the absence of some words in I John 5:7-8. The underlined phrase in this English translation was deleted:

For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three are one.

Erasmus said he did not include the phrase since he did not find it in any Greek manuscripts. Critics said he was attacking the Trinity by deleting a phrase clearly in the Vulgate Bible. Erasmus even had a friend check the Codex Vaticanus, a known ancient Bible manuscript in the Vatican library, to see if the phrase was in it – it was not. Nevertheless, under intense pressure from the Church, Erasmus included the phrase in his third edition, and thus it found its way into later Greek editions and the King James Bible. Scholars refer to the phrase as the Johannine Comma.

Leaf from Complutensian Polyglot. 1522, Isaiah 28:14b-28a

The Complutensian Polyglot was the first printed polyglot of the entire Bible, with the Bible printed in Hebrew, Latin, Greek, and Aramaic. The work was financed by Cardinal Francisco Ximenez (1436-1517), who acquired many manuscripts from which to print the versions. Begun in 1502, the work continued for fifteen years at the Complutense University in Alcala, Spain. The printing of the New Testament was completed in 1514 and included the first Greek New Testament printed. This was not published, however, until 1522, after the Old Testament was completed. Hearing of the printing of this Greek New Testament probably encouraged the Basel printer Johann Froben to rush a printing and publication of the Greek New Testament, making Erasmus’ work the first Greek New Testament published.

Erasmus said the first edition was “precipitated rather than edited” it was so rushed. The first printing of the Novum Instrumentum, completed in six months, was 1200 copies, which quickly sold. The font and design of the book were modern. This was the first book of Scripture which had each page numbered in Arabic numerals.

In Annotationes Novi Testament. Desiderius Erasmus. Basel:Johann Froben, 1516

Erasmus published a separate volume of Annotations to accompany his Greek and Latin Testament. Much as Lorenzo Valla before him, Erasmus noted and explained places where the Greek text differed from the Latin Vulgate, showing why a new Latin translation such as he had made was necessary. The Annotations also included criticisms of abuses in the church.

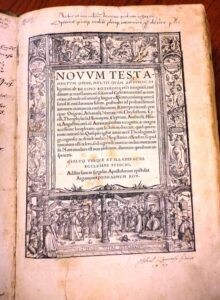

Novum Testamentum, 2nd edition. Desiderius Erasmus. Basel: Johann Froben, 1519

As soon as the first edition of his New Testament was published, Erasmus began revising and correcting the printing errors. He made over 400 changes for the second edition, including a change of the title from Novum Instrumentum to Novum Testamentum. One of his controversial changes was in John 1:1, where he changed the Latin translation verbum to sermo.

Three thousand copies were printed of Erasmus’ first two editions. Martin Luther used Erasmus’ second edition in making his translation of the New Testament into German, while at the Wartburg Castle. John Calvin used the first and second editions of Erasmus’ New Testament.

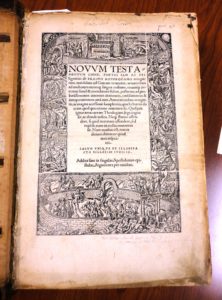

Novum Testamentum, 3rd edition. Desiderius Erasmus. Basel: Johann Froben, 1522

Erasmus’ third edition contained further revisions. Under pressure from his critics, Erasmus include the controversial “Johannine Comma” in I John 5:7-8, though it was not in most of the Greek manuscripts Erasmus consulted. The title also omitted the names of Origin, Athanasius, and other patristic commentators from the title. William Tyndale used the 3rd edition of Erasmus’ Novum Testamentum in making the first English translation of the New Testament from the Greek. A fourth and fifth edition were printed in 1527 and 1535.

In his Latin translation of this third edition, Erasmus, under pressure from Roman Catholic critics, replaced the Vulgate’s poenitentiam agite (do penance) with his translation of respiscite (repent) for the Greek word metanoiete.

Paraphrases of the New Testament

Erasmus’ Paraphrases of the New Testament were part of his effort to provide the Scriptures for all the people, developing a “philosophy of Christ” from the Bible, not from Aristotle as the scholastics did. The Paraphrases were very popular and translated into German in 1530, Hungarian in 1533, French in 1543, and English in 1548. The English translation was sponsored by Queen Catherine Parr, who helped with the translation of Matthew and Acts.

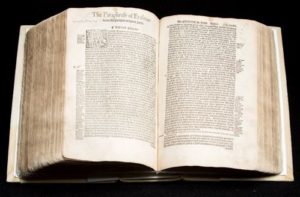

The First Tome or Volume of the Paraphrase of Erasmus upon the newe testament. Desiderius Erasmus. London: Edward Whitchurch, 1551, second edition.

This English Paraphrase of Erasmus combined Coverdale’s Great Bible translation of the New Testament with an English translation of Erasmus’ Latin Paraphrase of the New Testament. This first volume contained the four Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles. Queen Catherine Parr, King Henry VIII’s last wife, encouraged the translation of the Paraphrases into English, and the book was dedicated to her. The Queen probably translated parts of

Matthew and the Acts of the Apostles; Mary I, while a princes, translated the Gospel of John.

In 1547, King Edward VI ordered a copy of this work placed in every church in England. Erasmus’ commentary thus became the authorized commentary of the Church of England. When Mary came to the throne, she favored a return to the Latin Vulgate and ordered all copies of the Paraphrases destroyed, even though she had translated John’s Gospel.

Luther, Lefevre, and others criticized Erasmus’ Paraphrase, saying there was nothing which should replace the New Testament itself.

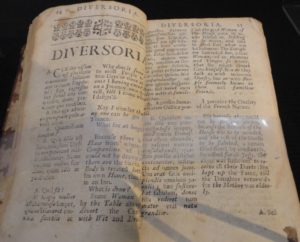

Erasmi Colloquia Selecta. Desiderius Erasmus 18th century?

This collection of 50 dialogues by Erasmus, in both Latin and English, on a variety of subjects, provided informal exercises for young people studying Latin. The book was reprinted extensively in both England and the United States throughout the mid-18th through the mid-19th century.

Erasmus’ Reformation Connections

Many of Erasmus’ writings influenced later leaders of the Reformation, and he shared many of the ideas so central to the Reformation:

- justification by faith,

- importance of the Scriptures as the foundation of faith,

- corruption of the clergy,

- the foolishness of ceremonialism, and

- the error of veneration of saints and relics.

Erasmus, however, never did break with the Church of Rome and became a critic of the leaders of the Reformation, thinking them divisive of the unity of the Church. Nevertheless, the Roman Catholic Council of Trent, which dealt with issues from the Reformation, placed all of Erasmus’ books on the Index of Prohibited Books.

Martin Luther (1483-1546) recognized Erasmus as the leading scholar in Europe and learned much from his works, especially his Greek/Latin New Testament. The first of Luther’s 95 Theses posted on the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg on October 31, 1517, are based on Erasmus’ corrected translation of repentance in Matthew 3:2:

- “Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when he said poenitentiam agite, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance.”

- “This word cannot be understood to mean sacramental penance i.e. confession and satisfaction, which is administered by the priests.”

- “Yet it means not inward repentance only; nay, there is no inward repentance which does not outwardly work divine mortification of the flesh.”

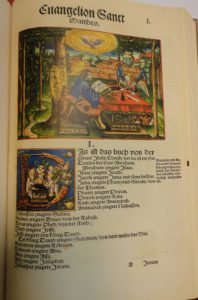

Biblia, das ist, Die gantze Heilige Schrift. Martin Luther, facsimile of 1st edition, 1534, 2 volumes. Köln: Taschen.

Martin Luther began translating the Bible into German during his friendly captivity at the Wartburg Castle. He used Erasmus’ second edition and frequently followed Erasmus’ reading of the Greek text rather than the Vulgate. Many other vernacular translators translated or made reference from Luther’s text, including translations into Dutch, English, Swedish. Danish, and Finnish.

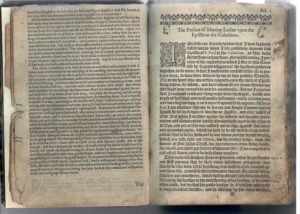

A Commentary upon the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians. Martin Luther.Philadelphia: Robert Aitken, 1801.

Martin Luther preached his first lectures on Galatians at Wittenberg shortly before he posted his 95 theses on October 27, 1517. He used Erasmus’ Greek New Testament in preparing his shorter commentary on Galatians, which was published in 1519. In the dedication, Luther wrote, “I, too, would certainly have preferred to wait for the commentaries promised long ago by Erasmus, a man preeminent in theology and impervious to envy. But since he is postponing this (God grant it may not be for long), the situation which you see forces me to come before the public.”

This is the first American edition, published by Robert Aitken, who also published the first English Bible in America. The subtitle reveals how important Galatians was to recovering the Gospel during the Reformation: “Wherein is set forth most excellently, the glorious riches of God’s grace, and the power of the gospel, with the difference between the law and the gospel, and the strength of faith declared; to the joyful comfort and confirmation of all true Christian believers, …”

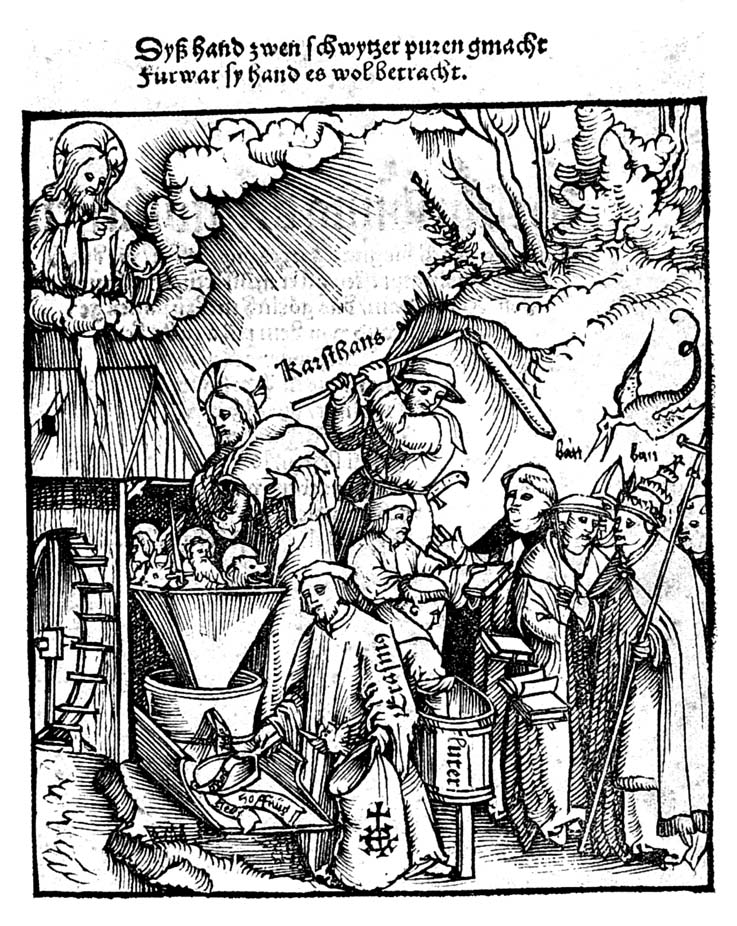

A broadside called “The Divine Mill,” printed by Hans Fussli in Zurich in 1521, shows Erasmus and Luther working together in the harvest of the Gospel. God the Father looks on as Jesus pours the 4 Evangelists into the hopper. Erasmus supervises the milling, and the “flour” comes out in cakes of faith, hope, love, and the church. Luther stands next to Erasmus, distributing Gospel books to the pope, a bishop, a monk and other men, all who refuse and let the books fall to the ground. A peasant with his scythe threatens divine vengeance on those refusing the Reformation.

A broadside called “The Divine Mill,” printed by Hans Fussli in Zurich in 1521, shows Erasmus and Luther working together in the harvest of the Gospel. God the Father looks on as Jesus pours the 4 Evangelists into the hopper. Erasmus supervises the milling, and the “flour” comes out in cakes of faith, hope, love, and the church. Luther stands next to Erasmus, distributing Gospel books to the pope, a bishop, a monk and other men, all who refuse and let the books fall to the ground. A peasant with his scythe threatens divine vengeance on those refusing the Reformation.

Though at first Erasmus praised Luther for his stand against ceremonialism and church corruption, as Luther spoke more boldly against the practices of the church and the papacy, Erasmus began to distance himself from Luther. Erasmus wanted to work for reform within the church, not separate from the Roman Church. He was encouraged to attack Luther, and in 1524 wrote On the Freedom of the Will. Luther’s response, On the Bondage of the Will, published in 1525, laid out foundational, Scriptural differences between the humanist scholar and the former Augustinian monk. Luther showed that Erasmus still clung to man’s works contributing to salvation rather than the grace of God.

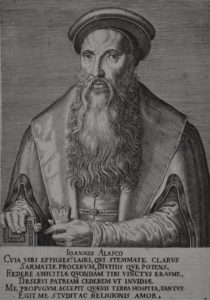

German scholar Johannes Oecolampadius (1482-1531) became cathedral preacher in Basel in 1515. Skilled in Greek and Hebrew, he became editorial assistant to Erasmus for the first edition of the Greek New Testament and Erasmus’ edition of the writings of St. Jerome. Oecolampadius praised Erasmus as the greatest scholar of his age. Erasmus praised Oecolampadius for his linguistic skill as well as his piety and theological knowledge. However, Oecolampadius and Erasmus became critical of each other as Oecolampadius sided with the development of the Reformation under Luther.

An outstanding scholar who entered the University of Heidelberg when only twelve, Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560) received his BA after only two years. He received his MA at seventeen from Tübingen and began teaching. When he was nineteen, Erasmus wrote of him, “To what hopes does this young man or rather this boy, give rise! What acumen of innovation, what purity of language, what mature erudition!”

When he was twenty-one, Melanchthon was recommended for the chair of Greek literature at Wittenberg University, where Melanchthon also studied theology with Martin Luther. The two men developed a life-long friendship. Melanchthon also developed a friendship and correspondence with Erasmus and tried to mediate the differences between Luther and Erasmus.

John Foxe, in his Book of Martyrs records William Tyndale (c.1494-1536) saying to a learned man upholding the pope’s authority against Scripture: “If God spare my life, ere many years I will cause a boy that driveth the plow shall know more of the scripture than thou doest.” The oft-quoted statement was a paraphrase from Erasmus’ Paraclesis.

Tyndale, the first English translator of the New Testament from the Greek, not only used Erasmus’ third edition of Novum Testamentum, but was influenced by Erasmus in other ways. Tyndale’s first known literary effort was the translation of Erasmus’ Enchiridion militis Christiani (Handbook of a Christian Knight) into English. Perhaps Erasmus’ praise of Bishop Tunstal encouraged Tyndale to apply, unsuccessfully, for work in London. Tyndale also carefully studied Erasmus’ Annotations and adopted his translation of the Greek ekklesia as the Latin congregatio, thus translating the word as congregation rather than church.

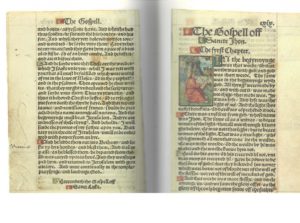

The Newe Testamente, 1st edition, facsimile. William Tyndale. Worms: Peter Schoeffer, 1526.

William Tyndale used Erasmus’ 1522 edition of the Greek text when he made the first translation of the New Testament into English. Because the Constitutions of Oxford had banned the Bible in English, Tyndale went to Germany, made his translation, had it printed, and then smuggled it back into England. Copies were burned in front of St. Paul’s Cathedral and elsewhere. Only two copies survived, one at St. Paul’s Cathedral, and one at the British Library. This facsimile was made from the British Library copy. In 1994, the British Library bought the volume for over £1 million, recognizing it as “the most important book in the English language.”

Martin Bucer (1491-1551) was a member of the Dominican Order who bought almost every one of Erasmus’ early publications. Bucer valued Erasmus’ emphasis on a simple faith in Christ and minimizing the importance of the ceremonies and ritual which had become much of the church’s life. Bucer also appreciated Erasmus’ attempt to restore the Bible to its central place in a philosophy of Christ. In 1518, Bucer met Martin Luther at the Heidelberg Disputation and became a leader of the Reformation in Strasbourg. Later, when Erasmus and Luther parted ways, Bucer supported Luther, believing his open and honest stand for the truth was needed in that day. In correspondence, Erasmus wrote Bucer, that he recognized the Church needed reform, but he saw no improvement in piety among the Protestants and would remain in the church in which he was born.

As a young pastor in Glarus and Einsiedeln, Switzerland, Ulrich Zwingli (1484-1531) studied Greek and Hebrew, as well as patristic authors and classical and scholastic works. He studied the works of Erasmus and met the humanist scholar in Basel sometime between 1514 and 1516. Zwingli’s turn to pacifism and preaching were both influenced by Erasmus. Erasmus’ poem “Jesus’ Lament to Mankind,” portraying Jesus as the bearer of salvation, caused Zwingli to abandon praying to the saints.

When Zwingli became pastor of the Grossmünster in Zurich, he began a series of sermons on the Gospel of Matthew from Erasmus’ New Testament. Zwingli memorized the Greek text of all the Pauline epistles. His sermons were a regular, orderly exposition of the Scriptures.

A graduate of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, Thomas Bilney (1495-1531) took holy orders in 1519, and came to faith in Christ by reading Erasmus’ 1516 Greek/Latin text. The first sentence he read was I Timothy 1:15, “This is a faithful saying, and worthy of all acceptance, that Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am chief.” Bilney said with joy, “I felt a marvelous comfort and quietness…After this, the Scripture began to be more pleasant unto me than the honey or the honeycomb; wherein I learned that all my labours, my fasting and watching, all the redemption of masses and pardons, being done without truth in Christ, who alone saveth his people from their sins; these I say, I learned to be nothing else but even…a hasty and swift running out of the right way.” ( P.R.N. Carter, “Thomas Bilney,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/2400.)

Bilney began to study the Scriptures and began a Bible study in Cambridge. He influenced many other young men in the Scriptures, including Matthew Parker, future Archbishop of Canterbury, and Hugh Latimer. Bilney began preaching against the mediation and veneration of the saints and the spiritual efficacy of pilgrimages. He was arrested for heresy and executed in 1531, one of the early martyrs of the English church.

John Calvin (1509-1564) shared Erasmus’ emphasis on the Greek and Latin classics and the importance of grammar and rhetoric. Calvin followed Erasmus in going back to the original sources, especially the Bible, and studying the church fathers and early church history. Calvin’s first published work, in 1532, was a commentary on Seneca’s De Clementia, a work Erasmus had edited in 1529. Calvin boasted of the errors he had found in Erasmus’ work.

Erasmus was living in Basel when Calvin came to Basel in 1535, but there is no record that the two met. Calvin published the first edition of his Institutes in Basel in 1536; Erasmus died there three months later. Calvin’s commentaries and works are full of references to Erasmus. In the last edition, 1559, of the Institutes, Calvin used Erasmus’ term to describe the Gospel as “Christian philosophy.”

Calvin used the first and second editions of Erasmus’ Greek text. He lectured directly from the Greek, without notes.

Born into a wealthy Polish family, Jan Laski (1499-1560) met Erasmus when he was twenty-five and Erasmus in his sixties. Laski stayed with Erasmus for a year in 1525, liberally helping defray Erasmus’ expenses and paying Froben for publication of some of Erasmus’ works. Erasmus praised Laski’s “golden disposition” and spotless purity, calling him “a true pearl.”

For seven years Laski was pastor of the Protestant church in Emden. When persecution forced him to leave, he went to England. There he stayed at Lambeth with Cranmer, advised Edward VI, and oversaw congregations of foreigners in London. With Mary’s accession, Laski had to flee again. He finally returned to Poland where he became a leader of the Polish Reformation. He is one of the translators of the 1563 Brest Bible, the first Polish Bible translated from the Hebrew and Greek.

Lady Jane Grey (1537-1554) was an extremely well educated teenager who knew Latin, Greek, and Hebrew and corresponded with leading reformers on the continent. Queen for nine days after the death of King Edward VI, the people did not accept Jane, and Queen Mary assumed the throne. Mary executed Jane for treason in 1554. The day before her execution, Jane gave her Greek New Testament to her sister Katherine. At the back of the Testament, she wrote a letter expressing her Christian faith:

I have sent you, my dear sister Katherine, a book, which although it be not outwardly trimmed with gold, or the curious embroidery of the artfulest needles, yet inwardly it is more worth than all the precious mines which the vast world can boast of: it is the book, my only best, and best loved sister, of the law of the Lord: it is the Testament and last will, which he bequeathed unto us wretches and wretched sinners, which shall lead you to the path of eternal joy: and if you with a good mind read it, and with an earnest desire follow it, no doubt it shall bring you to an immortal and everlasting life: it will teach you to live, and learn you to die: it shall win you more, and endow you with greater felicity … (Lady Jane Grey Reference Guide.)

Textus Receptus

The Greek text of the New Testament printed by Erasmus was based on manuscripts no earlier than the twelfth century. Revised and corrected by comparison with other manuscripts, also dated late, this became known as the Textus Receptus or the received text. Since the 16th century, thousands of earlier manuscripts have been found, some dating to the second century, which have variants from the Textus Receptus, showing scribal additions over the centuries. The famous Johannine Comma, the last verses of Mark 16, and the woman taken in adultery in John 8 are three examples of additions found in the Textus Receptus and not in the earliest manuscripts. Most modern translations are based on earlier manuscripts, hence the differences between the text of the King James Version and later translations

Novum Testamentum. Robert Stephanus, Geneva, 1550.

This third edition of the Greek New Testament printed by the famous printer Robert Estienne, whose Latinized name is Stephanus, is known as the Editio Regia because of the elegance of its Greek font. This text is the first Greek Testament with a critical apparatus, marginal notes giving the variant readings from different Greek manuscripts.

In preparing this Greek text, Estienne closely followed Erasmus’ Greek text, as in his fourth and fifth editions, and compared the readings with fifteen manuscripts and the Complutensian Polyglot. For many, this edition of the Greek text became the norm for the Greek New Testament. Stephanus’ oldest son, Henri, was a young classical scholar who did much of the work for the collation of the manuscripts and Greek texts.

Kaine Diatheke. Novum Testamentum: Ex Regiis aliisque optimis editianibus, hac nova expressum: cui quid accesserit, præfatio docebit. Lugd. Batavorum [Leiden], Elzevir, 1633.

This Greek text of the New Testament, published by the famed Dutch printers Bonaventure and Abraham Elzevir, is based on Erasmus’ and Stephanus’ earlier work in textual criticism and claims to have removed all mistakes in the printing and text. The preface stated in Latin “ so you hold the text, now received by all, in which (is) nothing corrupt” (Textum ergo havhabes, nunc ab omnibus receptum: in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum damus). This came to be known as the Textus Receptus, or the received text, and was retroactively applied to Erasmus’ Greek text, which was foundational to all others.

Vernacular Translations

Preserved Smith noted that Erasmus’ Greek New Testament “was the fountain and source from which flowed the new translations into the vernaculars which like rivers irrigated the dry lands of the medieval Church and made them blossom into a more enlightened and lovely form of religion.” (Preserved Smith. Erasmus, A Study of His Life, Ideals, and Place in History. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1962, 185.) Within a few decades, entire households at all levels of society had the Bible to intimately influence their daily lives. The following are early Bible translations flowing from Erasmus’ Greek text –

- 1522 – German by Martin Luther

- 1523 – New Testament in Dutch

- 1524 – Danish New Testament

- 1525 – English by William Tyndale

- 1526 – Swedish

- 1526 – whole Bible in Dutch

- 1530 – Italian New Testament from Erasmus’ Latin

- 1532 – Italian whole Bible

- 1533 – Benedek Komjati used Erasmus’ Greek text to translate Paul’s epistles into Hungarian

- 1535 – French Neuchâtel Bible by Olivetan from Erasmus’ Latin text

- 1543 – Spanish New Testament by Francisco de Enzinas

- 1548 – Finnish New Testament, translated from the Greek

- 1563 – Brest Bible, translation into Polish from Hebrew and Greek

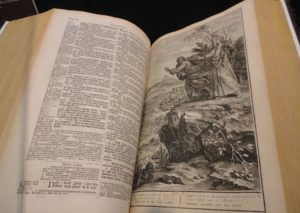

The Holy Bible Conteyning the Old Testament and the New London: Robert Barker, 1611/1613.

The translators of the King James Version followed the Greek text known as the Textus Receptus, founded in Erasmus’ Greek Testament. This second folio edition of the King James Version is sometimes called the “she” Bible, for the reading at Ruth 3:15 “and she went into the citie.”

Biblia, dat is De gantsche H. Schrifture, vervattende alle de Canonijcke Boecken des Ouden en des Nieuwen Testaments. The Stattenvertaling, or States Bible. Hendrick and Jacob Keur, Marcus Doomick, Dordrecht, Amsterdam, 1682

In 1618/19 the Synod of Dort requested the States-General of the Netherlands to commission a translation of the Bible into Dutch from the original Hebrew and Greek languages. The States-General commissioned the work in 1626. The translation was completed in 1635, and the States-General authorized the work in 1637. The New Testament was translated from the Textus Receptus. The States Bible became the standard Dutch translation of the Bible, influencing the Dutch language and underlying a unified culture in the Netherlands.

In the Scriptures are my Joy and Peace

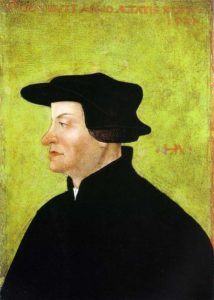

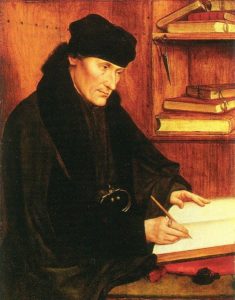

Portrait of Erasmus painted in 1517 by Quentin Massys in Antwerp. The painting was a gift to Sir Thomas More, at whose house Erasmus had stayed while in England and while More was working on his Utopia.

Portrait of Erasmus painted in 1517 by Quentin Massys in Antwerp. The painting was a gift to Sir Thomas More, at whose house Erasmus had stayed while in England and while More was working on his Utopia.

Erasmus was working on his Paraphrase of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans. However, Erasmus’ writing has been erased and the page is blank, probably out of antipathy to the importance of Paul’s Roman epistle to the Reformation and that Erasmus’ writings had been prohibited by the Council of Trent. The portrait is in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica in Rome.

In 1526, Erasmus wrote a letter to Gattinara, Chancellor to the Emperor Charles V, in which he said,

It is I, as cannot be denied, who has aroused the study of languages and good letters. I have brought academic theology, too much subjected to sophistic contrivances, back to the source of the holy books and the study of ancient orthodox authors; I have exerted myself to awaken a world slumbering in pharisaic ceremonies to true piety.

Erasmus believed

The sum of all Christian philosophy amounts to this: – to place all our hopes in God alone, who by his free grace, without any merit of our own, gives us every thing through Christ Jesus; to know that we are redeemed by the death of his Son; to be dead to worldly lusts; and to walk in conformity with his doctrine and example, not only injuring no man, but doing good to all; to support our trials patiently in the hope of a future reward; and finally, to claim no merit to ourselves on account of our virtues, but to give thanks to God for all our strength and for all our works. This is what should be instilled into man, until it becomes a second nature. (Ad Joh. Sclechta, 1519.)

To Erasmus, the most important of all his endeavors was the study of the Scriptures, and he wrote, “I am firmly resolved to die in the study of the Scriptures; in them are all my joy and all my peace.” Ad Servatium.