The Geneva Bible: The First English Study Bible

The Geneva Bible was at the foundation of the American Colonies. It was the Bible used in Jamestown and the preferred Bible of the early Pilgrim settlers of New England. The Geneva Bible was the Bible of the leading English writers John Bunyan, William Shakespeare, and John Milton.

The Geneva Bible was at the foundation of the American Colonies. It was the Bible used in Jamestown and the preferred Bible of the early Pilgrim settlers of New England. The Geneva Bible was the Bible of the leading English writers John Bunyan, William Shakespeare, and John Milton.

When Mary Tudor became queen in 1553, many English Protestants fled to Europe, seeking refuge from religious persecution. By 1560, English exiles in Geneva produced a Bible in English especially designed for use by families and individuals. The translation, the first complete Bible into English from both the Hebrew and Greek, was excellent. Yet, the most important element of this Bible, which came to be known as the Geneva Bible, was its notes. Marginal notes included cross-references, alternative translations, and explanations of the “hard places” of Scripture. The notes provided a running commentary on Scripture and shaped the understanding of the Bible for generations of ordinary English-speaking people

After Darkness, Light

16th Century Geneva was a center of the Reformation, and scholars from throughout Europe came to study there. The city’s numerous printing presses spread the biblical teaching of the Reformation from Geneva to the rest of Europe. Geneva adopted as its motto, post tenebras, lux (after darkness, light) as a declaration of the light the teaching of the Scripture brought to the life of the city itself.

The Geneva Bible included several “firsts” for an English Bible:

- Used Roman type (rather than black letter or Gothic), making the text

easier to read; - Divided the text into verses, making cross-references and concordances easier to use;

- Added italicized words for words not in the original Greek or Hebrew but needed for English understanding.

In addition, - Chapter summaries were placed before each chapter;

- Subject headliners were placed at the top of each page;

- A synopsis preceded each book;

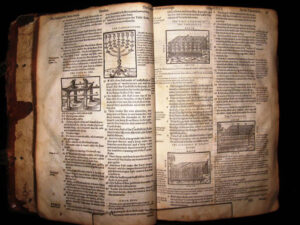

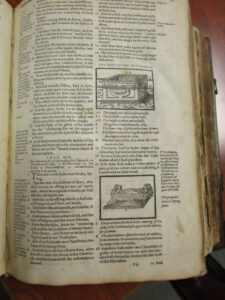

- 26 illustrations were incorporated in the Old Testament;

- Five maps on separate leaves were included;

- End supplements included interpretation of proper names, principal teachings of Scripture, and Bible chronology.

This was a Bible for the ordinary Christian to read and study.

Biblical Texts Used by the Genevan Translators

The Genevan translators built upon a half century of translation work and scholarly study of the biblical texts. They  consulted not only the earlier English translations, but also recent translations into German, French, Italian , Spanish, and Latin, as well as scholarly editions of the Greek and Hebrew texts.

consulted not only the earlier English translations, but also recent translations into German, French, Italian , Spanish, and Latin, as well as scholarly editions of the Greek and Hebrew texts.

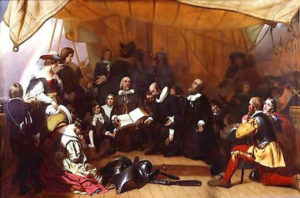

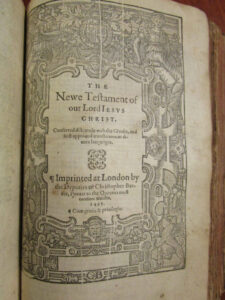

The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ: Published in 1526; William Tyndale, translator; Andover: Gould and Newman, 1837.

This is an 1837 reprint of William Tyndale’s New Testament translation. William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament into English was an important reference for the Genevan translators, probably in the 1552 edition published by Richard Jugge.

Biblia Sacra, Theodore Beza, translator; Amsterdam, 1648.

Biblia Sacra, Theodore Beza, translator; Amsterdam, 1648.

Theodore Beza (1519-1605) was a professor of theology and assistant to John Calvin, who succeeded him as leader of the Genevan Church and Academy. He published several editions of a Greek text of the New Testament. Even more influential than his Greek New Testament was his heavily annotated Latin translation. His Latin translation with notes was extensively used by the Genevan translators as well as the later translators of the King James Bible.

Beza published several editions of his Latin Bible during his lifetime, and it continued to be published after his death. This version, published in Amsterdam in 1648, includes Beza’s Latin New Testament and a Latin translation of the Hebrew Old Testament by Francis Junius.

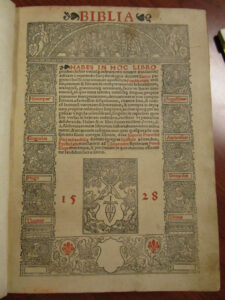

Biblia, translated by Sanctes Pagninus, Lyons, 1528.

Biblia, translated by Sanctes Pagninus, Lyons, 1528.

Sanctes Pagninus’ translation of the Bible into Latin was the first complete translation of the Bible from the original Hebrew and Greek since Jerome’s Vulgate translation of the fourth century. Since Latin was still the universal language of education, Pagninus’ translation was for the educated, and

translation of the fourth century. Since Latin was still the universal language of education, Pagninus’ translation was for the educated, and

demonstrated the degree to which the medieval Latin Vulgate deviated from the original Hebrew and Greek. This edition was also the earliest in which the text is divided into numbered verses. Pagninus’ verse divisions were not adopted by later Bibles, however. 09.728 Donald Brake Collection

Novum Testamentum Jesu Christi ; Printed by Robert Estienne ;

Geneva, 1551.

Robert Estienne (1503-1559) was a Paris printer who relocated to Geneva to escape persecution. Skilled in ancient languages, Robert printed four editions of the Greek New Testament, the last in Geneva. His editions not only show excellent printing craftsmanship, but they include careful comparisons of the available Greek manuscripts, early steps in modern textual criticism. Estienne’s New Testament published in Geneva included Erasmus’ Latin translation and the Latin Vulgate.

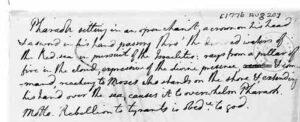

John Calvin & the Council of Geneva, 1549

John Calvin & the Council of Geneva, 1549

Early 20th century print, after painting by

Pierre Labouchere (1807 – 1873).

John Calvin and his teaching had a powerful influence both in Geneva’s government and church. Calvin worked intimately with the translation and production of French Bibles in Geneva. Many of the features of the French printed Bibles were incorporated into the English Geneva Bible – features such as verse divisions, summaries before each book, chapter headings, page headers, and extensive marginal commentaries.

Popularity of the Geneva Version

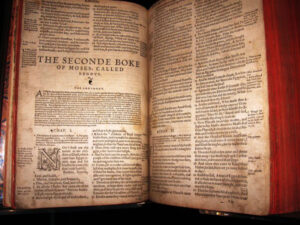

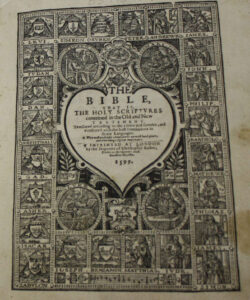

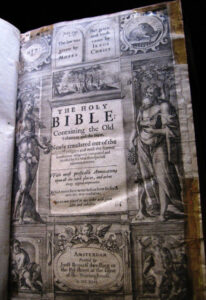

The Bible and Holy Scriptures conteyned in the Olde and Newe Testament; First edition; Geneva, printed by Rowland Hall, 1560.

This English Bible translation became known as the Geneva Bible, for the place it was translated and first printed. Because of its compact size, readable Roman type, affordability, and explanatory notes, it soon became popular with the English people. The Bible also included 26 engravings and 5 individual maps. The first edition included a dedication to “the moste virtuous and noble Quene Elizabeth”, who ascended the throne in 1559. Here the English exiles encouraged the Queen from the Scriptures in the godly responsibilities of a Christian ruler. An address “To our Beloved in the Lord our brethren in England, Scotland, Ireland” encouraged the people in the Scri

This English Bible translation became known as the Geneva Bible, for the place it was translated and first printed. Because of its compact size, readable Roman type, affordability, and explanatory notes, it soon became popular with the English people. The Bible also included 26 engravings and 5 individual maps. The first edition included a dedication to “the moste virtuous and noble Quene Elizabeth”, who ascended the throne in 1559. Here the English exiles encouraged the Queen from the Scriptures in the godly responsibilities of a Christian ruler. An address “To our Beloved in the Lord our brethren in England, Scotland, Ireland” encouraged the people in the Scri ptures.

ptures.

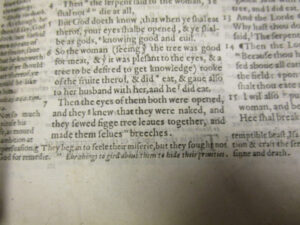

The Geneva Bible has sometimes been called the “Breeches Bible”, after the translation of Genesis 3:7: Adam and Eve “sewed figge tree leaves together, and made themselves breeches.” However, the Wycliffite translation of the 14th century had also translated the first couple’s fig-leaf clothing as

“breeches.”

The second and third edition of the Geneva Bible were printed in Geneva in 1562 and 1570. Not until after the death of Archbishop Parker in 1575 was a Geneva version printed in England. Archbishop Parker led the Anglican bishops in a translation published in 1568, known as the Bishops’ Bible. Parker vainly hoped that this translation would supersede the Geneva translation. The Geneva version easily surpassed the Bishops’ translation in popularity, and over 140 editions were printed in ensuing years.

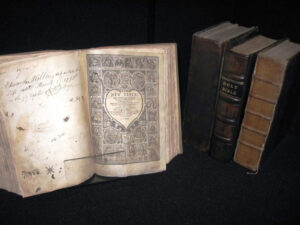

Knightley Family Bible – Holy Bible, printed by Christopher Barker, London, 1577.

This Geneva Bible, one of the earliest printed in England, belonged to Richard and Elizabeth Knightley. The Knightleys were Puritans and close to the court of Elizabeth I. Elizabeth Knightley was the niece of Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s wife and mother of Edward) and the daughter of Edward Seymour (Lord Proector under young

This Geneva Bible, one of the earliest printed in England, belonged to Richard and Elizabeth Knightley. The Knightleys were Puritans and close to the court of Elizabeth I. Elizabeth Knightley was the niece of Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s wife and mother of Edward) and the daughter of Edward Seymour (Lord Proector under young  King Edward VI). The blank pages in the front of the Bible were used for noting the births of children and for some Bible study notes. Notice that the witness to the birth of the child born in October 1588 (a few weeks after the defeat of the Spanish Armada’s invasion of England ) was “her Majesty [i.e. Queen Elizabeth] and the Lord Treasurer…”

King Edward VI). The blank pages in the front of the Bible were used for noting the births of children and for some Bible study notes. Notice that the witness to the birth of the child born in October 1588 (a few weeks after the defeat of the Spanish Armada’s invasion of England ) was “her Majesty [i.e. Queen Elizabeth] and the Lord Treasurer…”

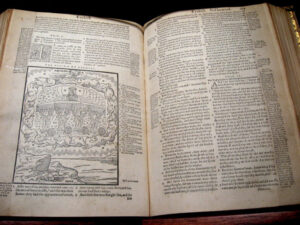

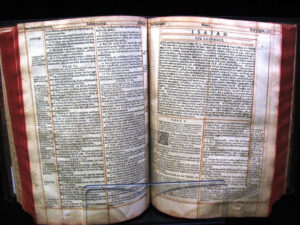

The Bible that is, the Holy Scriptvres conteined in the Olde and Newe Testament. Translated according to the Ebrewe and Greeke, London, printed by Christopher Barker, 1577.

Maps and illustrations in the Geneva Bible were specifically designed for instruction. Here the articles of furniture in the Jewish tabernacle are illustrated. These illustrations were originally designed for Robert Estienne’s Lat

Maps and illustrations in the Geneva Bible were specifically designed for instruction. Here the articles of furniture in the Jewish tabernacle are illustrated. These illustrations were originally designed for Robert Estienne’s Lat in Bible, printed in Paris in 1540. They were made with the assistance of Hebrew scholars François Vatable. Other illustrations in the Geneva Bible included the Tabernacle of Moses, the Temple of Solomon, and the visionary Temple of Ezekiel.

in Bible, printed in Paris in 1540. They were made with the assistance of Hebrew scholars François Vatable. Other illustrations in the Geneva Bible included the Tabernacle of Moses, the Temple of Solomon, and the visionary Temple of Ezekiel.

King James’ Disdain for the Geneva Bible

Though King James VI of Scotland authorized the Geneva Version to be

the first Bible printed in Scotland, he came to vehemently dislike the

marginal notes – such as those at Exodus 1:

- At verse 19, the note concerning the midwives who did not follow Pharaoh’s command to kill the newborn boys of Israel said: “Their disobedience was lawful, but their dissembling was evil.”

- At verse 22: “when tyrants cannot prevaile by craft, thei burst for the into outrage.”The Geneva Bible notes always were against tyranny and did not support the divine right of kings so dear to James. When James became King James I of England, he authorized a Bible translation specifically to be

without notes – the King James Version of 1611.

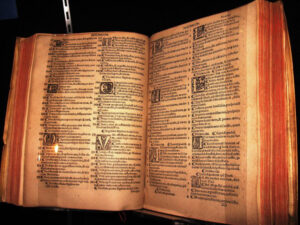

First Bible Printed in Scotland – The Bible and Holy Scriptures Conteined in the Ole and Newe Testament, printed by Thomas Bassandyne, 1579.

First Bible Printed in Scotland – The Bible and Holy Scriptures Conteined in the Ole and Newe Testament, printed by Thomas Bassandyne, 1579.

Scotland’s King James VI (later King James I of England) authorized the Geneva Version as the first Bible printed in Scotland. . The King also authorized at least one  copy be kept in every church in Scotland. The Scottish parliament went further and required every “householder worth 300 marks of yearly rent and all yeomen and burgesses worth 500 pounds in lands and goods” have a Bible and psalm book in the common language. A fine of £10 was assessed for non-compliance.

copy be kept in every church in Scotland. The Scottish parliament went further and required every “householder worth 300 marks of yearly rent and all yeomen and burgesses worth 500 pounds in lands and goods” have a Bible and psalm book in the common language. A fine of £10 was assessed for non-compliance.

Chained Geneva Bible with wooden cover; London, printed by deputies of Christopher Barker, 1595.

Chained Geneva Bible with wooden cover; London, printed by deputies of Christopher Barker, 1595.

In 1538 Henry VIII for the first time ordered that an English Bible be placed in every church in England. Often Bibles were chained to the pulpit to prevent theft. Most of the “chained Bibles” were Great Bibles, a translation completed by Myles Coverdale and usually published as large folio Bibles designed specifically for church use. Geneva Bibles were usually used at home, and it is unusual to find a chained Geneva Bible. The wooden cover of the Bible is adorned with a carving of an angel and the Ten Commandments.

The Bible translated according to the Hebrew and Greek, and conferred with the best translations in diuers languages; with most profitable annotations upon all the hard places, and other things of great importance, London, Christopher Barker, 1594.

This Geneva Bible edition has a notable misprint on the New Testament title page – which states it was published in 1495!

1495!

Many later Geneva Bibles included extra materials for study and worship beyond the initial Geneva notes. The Book of Common Prayer, which included Bible reading schedules and prayers, was placed in front of many Bibles. This included the translation of the psalms used in Anglican Church services (a translation of the psalms done by Myles Coverdale for the Great Bible of 1540). Often, Thomas  Sternhold and John Hopkins’ metrical version of the psalms used for singing was placed at the end of the Bible. In such cases, the Bible would have three translations of the book of psalms – Coverdale’s in the Book of Common Prayer, the Geneva translation in the Bible itself, and the metrical psalms placed at the end of the Bible!

Sternhold and John Hopkins’ metrical version of the psalms used for singing was placed at the end of the Bible. In such cases, the Bible would have three translations of the book of psalms – Coverdale’s in the Book of Common Prayer, the Geneva translation in the Bible itself, and the metrical psalms placed at the end of the Bible!

The Bible: That Is, the Holy Scriptures Conteined in the Olde and Newe Testament, Translated According to the Ebrew and Greeke, and conferred with the best translations in divers languages. With most profitable annotations upon all the hard places, and other things of great importance. London, Christopher Barker, 1587

Like many later Geneva Bibles, this contains at the end The Whole Booke of Psalmes, collected into English metre” byThomas Sternhold and John Hopkins.

The New Testament of Our Lord Jesus Christ, translated out of the Greek by Theodore Beza, whereunto are added brief summaries of doctrine, and also a short exposition on the phrases and hard places, Englished by L. Tomson, Second edition, London, 1589

The first edition of Puritan Laurence Tomson’s New Testament was issued in 1576. This English translation of Theodore Beza’s Latin translation from the Greek included copious notes. The translation itself was marked by translating the definite article “that” as in John 1:1 here. Most Geneva Bibles published after 1590 replaced the original New Testament translation and notes with Tomson’s. Tomson was a Member of Parliament and an aide to Sir Francis Walsingham, a key advisor to Queen Elizabeth I.

The first edition of Puritan Laurence Tomson’s New Testament was issued in 1576. This English translation of Theodore Beza’s Latin translation from the Greek included copious notes. The translation itself was marked by translating the definite article “that” as in John 1:1 here. Most Geneva Bibles published after 1590 replaced the original New Testament translation and notes with Tomson’s. Tomson was a Member of Parliament and an aide to Sir Francis Walsingham, a key advisor to Queen Elizabeth I.

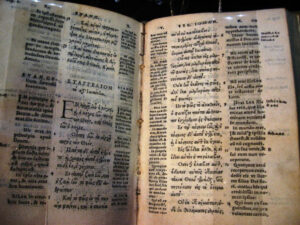

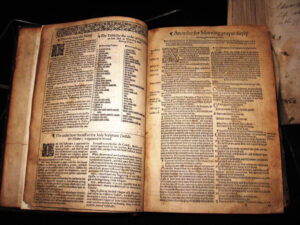

Geneva Bible’s notes in Romans – The Bible, London, Christopher Barker, 1599

Laurence Tomson’s English translation of Theodore Beza’s New Testament and notes were used in most G eneva Bible editions after 1590. The notes were most extensive in the book of Romans and reflected the biblical teaching of Calvin’s Geneva.

eneva Bible editions after 1590. The notes were most extensive in the book of Romans and reflected the biblical teaching of Calvin’s Geneva.

The notes made the Scriptures more understandable to the reader and were of several kinds:

- Variant translation possibilities

- Scriptural cross-references (for, Scripture was its own best interpreter)

- Doctrinal explanations

- Definitions

- Historical background and information about Hebrew rituals.

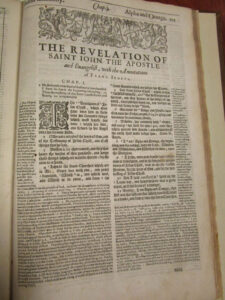

Francis Junius’ Notes in Revelation – The Bible, That is, the holy Scriptures conteined in the Olde and New Testament printed by Robert Barker; London, 1616

Probably the most influential commentary on the book of Revelation ever written  was Francis Junius’ A Brief and Learned Commentary, first published in English in 1596. In 1599, Junius’ notes on Revelation were incorporated in the Geneva Bible. The “Order of Time” placed before the Book of Revelation, was to help the reader understand the progress of historical events in the book. Junius, along with John Bale and John Foxe, interpreted the book of Revelation as the unfolding history of the church. They saw two churches in Revelation, one of the spirit and one of the flesh. One followed Jesus in humble poverty and truth; the other accumulated wealth and worldly power, teaching blasphemous errors. Junius, Bale, and Foxe were among the Reformers who saw the Pope and the Roman Church as the false religion of Revelation.

was Francis Junius’ A Brief and Learned Commentary, first published in English in 1596. In 1599, Junius’ notes on Revelation were incorporated in the Geneva Bible. The “Order of Time” placed before the Book of Revelation, was to help the reader understand the progress of historical events in the book. Junius, along with John Bale and John Foxe, interpreted the book of Revelation as the unfolding history of the church. They saw two churches in Revelation, one of the spirit and one of the flesh. One followed Jesus in humble poverty and truth; the other accumulated wealth and worldly power, teaching blasphemous errors. Junius, Bale, and Foxe were among the Reformers who saw the Pope and the Roman Church as the false religion of Revelation.

This folio Geneva Bible contains both the Book of Common Prayer and the metrical Psalms, as well as the Geneva translation and notes. Though most Geneva Bibles were in roman type, some, as this edition, were printed in black letter, with the notes in roman font.

People of a Book

With the widespread availability of the Geneva Bible, the Bible became the one book familiar to every Englishman. England became a people of a book – the Bible. The Bible was the literature of the people, molding their speech , shaping their language, permeating their thoughts, and changing the entire moral character of the nation. As the Bible was read and discussed, literacy and education grew among all classes of both men and women.

Reading the Bible by Hughes Merle, c. 1859

Reading the Bible by Hughes Merle, c. 1859

Courtesy of The Wallace Collection, London

Geneva Bibles from 1599?

King James could not abide the Geneva Bible. Its notes were clearly republican in nature and against absolute monarchy. But, when the King James Version was published in 1611, it could not compete with the popularity of the  Geneva Bible, the household Bible of the English. To encourage the production of his sponsored translation (which actually followed the Geneva Version in most places!), King James in 1616 banned the production of the Geneva Bible in

Geneva Bible, the household Bible of the English. To encourage the production of his sponsored translation (which actually followed the Geneva Version in most places!), King James in 1616 banned the production of the Geneva Bible in

England. When Geneva Bibles continued to be printed abroad and imported into England, Archbishop Laud banned the importation of the Geneva Bible. The Geneva Bible continued to be printed abroad and imported, however . Printers in Amsterdam printed Geneva Bibles for several decades, with title pages saying the Bibles were printed in 1599 by Christopher Barker in London! Bibliographers carefully studying these editions have been able in many cases to date them into the 1630’s and 1640’s.

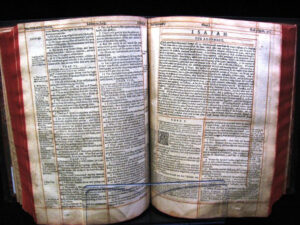

Geneva Bible; c. 1630 (though title page says 1599, Christopher Barker, London)

Geneva Bible; c. 1630 (though title page says 1599, Christopher Barker, London)

This Bible has red lines hand-drawn throughout, separating the notes from the text and marking the two columns, making it easier to read.

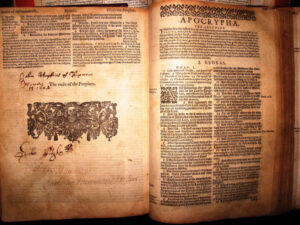

Hammond Family Bible, with Apocrypha; Geneva Bible, labeled as 1599, but published in 1630

The books called “Apocrypha” were twelve books not in the original Hebrew Bible, but included in the Septuagint, a third century B.C. Greek translation of the Old Testament. Though Jerome did not consider these books as Scripture,  they were included in his Vulgate translation and came to be accepted as canonical. The books were often intermixed with the canonical Old Testament and even used in church liturgies. The leaders of the Reformation did not recognize these books as Scripture. In his English translation, Myles Coverdale was the first to separate apocryphal books from the Old Testament. He placed them between the two testaments, explaining they contained things which were “repugnant to the manifest truth of the other books of the Bible.” The 1547 Council of Tent, however, affirmed the books as Scripture for the Roman Catholic Church. The 1560 Geneva Bible contained the Apocrypha, but it was

they were included in his Vulgate translation and came to be accepted as canonical. The books were often intermixed with the canonical Old Testament and even used in church liturgies. The leaders of the Reformation did not recognize these books as Scripture. In his English translation, Myles Coverdale was the first to separate apocryphal books from the Old Testament. He placed them between the two testaments, explaining they contained things which were “repugnant to the manifest truth of the other books of the Bible.” The 1547 Council of Tent, however, affirmed the books as Scripture for the Roman Catholic Church. The 1560 Geneva Bible contained the Apocrypha, but it was  separated from the rest of Scripture and contained almost no marginal notes. Many later editions of the Geneva Bible did not contain the Apocrypha. When the books were included, the preface always noted that these might be read for edification, but did not have the authority of Scripture. Hammond Family Bible includes handwritten family records dating from 1609-1874. Charles Hammond, d. 1794, was a Secretary of the Virginia House of Delegates before the Revolutionary War. He moved to South Carolina at the beginning of the Revolution; his 5 sons all fought in the Revolution.

separated from the rest of Scripture and contained almost no marginal notes. Many later editions of the Geneva Bible did not contain the Apocrypha. When the books were included, the preface always noted that these might be read for edification, but did not have the authority of Scripture. Hammond Family Bible includes handwritten family records dating from 1609-1874. Charles Hammond, d. 1794, was a Secretary of the Virginia House of Delegates before the Revolutionary War. He moved to South Carolina at the beginning of the Revolution; his 5 sons all fought in the Revolution.

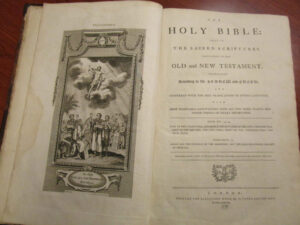

King James Version with Geneva Notes, Amsterdam, 1642

The first King James Version avowedly printed abroad was this edition printed in Amsterdam. Though King Jame s clearly forbade his commissioned version to have notes, the Amsterdam publishers saw fit to place the very popular Geneva Bible notes, including Junius’ notes on Revelation, with the King James Version.

s clearly forbade his commissioned version to have notes, the Amsterdam publishers saw fit to place the very popular Geneva Bible notes, including Junius’ notes on Revelation, with the King James Version.

Imagery on the title page includes the sacred name of God, the Lamb of God and the book with the 7 seals, a scene of man’s fall, Adam and Noah (the progenitors of the human race), and a child (the seed of the woman of Genesis 3:15) overcoming death and the serpent.

Geneva Bible; London, printed by Alexander Hogg, 1778

Many have asserted that no Geneva Bibles were printed after 1644. Yet, this folio Geneva Bible was printed over 130 years later – in London in 1778. Though the Bible opens with Archbishop Parker’s preface to the Bishops’ Bible, the text and notes are all the Geneva version.

Many have asserted that no Geneva Bibles were printed after 1644. Yet, this folio Geneva Bible was printed over 130 years later – in London in 1778. Though the Bible opens with Archbishop Parker’s preface to the Bishops’ Bible, the text and notes are all the Geneva version.

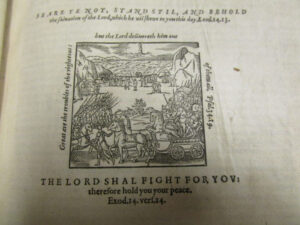

Freedom from Tyranny

The title page of the Geneva Bible featured the scene of the Israelites preparing to cross the Red Sea. Pharaoh’s army is in pursuit, and Moses, with the pillar of cloud overhead, raises his rod to part the waters. The picture is surrounded by Scripture quotes: “Great is the trouble of the righteous, but the Lord delivers them out of all, Psalm 34:19 “Fear not, stand still and beholde the salvation of the Lord which he will shew to you this day,” Exodus 14:13

The title page of the Geneva Bible featured the scene of the Israelites preparing to cross the Red Sea. Pharaoh’s army is in pursuit, and Moses, with the pillar of cloud overhead, raises his rod to part the waters. The picture is surrounded by Scripture quotes: “Great is the trouble of the righteous, but the Lord delivers them out of all, Psalm 34:19 “Fear not, stand still and beholde the salvation of the Lord which he will shew to you this day,” Exodus 14:13

The scene and Scriptures symbolized the longings of the English exiles in Geneva – a longing to return to their own land and be free from the oppressive rule of a tyrannical ruler.

After the approval of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson recommended a design for a state seal for the new United States. Their design was very similar to the Geneva Bible’s illustration of the Israelites preparing to across the Red Sea – Pharaoh’s army is in pursuit, and Moses, with the pillar of cloud overhead, raises his rod to part the waters. Many in the young United States saw parallels between their war for freedom against Great Britain and Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian tyranny.

design for a state seal for the new United States. Their design was very similar to the Geneva Bible’s illustration of the Israelites preparing to across the Red Sea – Pharaoh’s army is in pursuit, and Moses, with the pillar of cloud overhead, raises his rod to part the waters. Many in the young United States saw parallels between their war for freedom against Great Britain and Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian tyranny.