[By: Cora Barnhart, 2024]

Abstract

During the Exodus, time spent in the desert was intended to provide the Israelites the discipline necessary to learn to rely on God. Once inside the Promised Land, they moved away from this discipline. In the same way success can lead organizations to forsake core values and lose their competitive advantage. The Israelites’ experience from their initial entry into and eventual exit (exile) from the Promised Land provides a useful framework for studying decline in otherwise successful companies. The Israelites’ behavior during their occupation of the Promised Land is analyzed using Collins’ five stage model of corporate failure, where comparable missteps committed by corporations are highlighted. This comparative study offers helpful insights from the Promised Land experience and suggests how a repentance process could help mitigate strategic errors that contribute to organizational failures.

Introduction

In October 2018, a Lion Air 737 Max crash in Indonesia killed 189 passengers. Less than five months later, global regulators grounded Boeing’s newly designed Max 737 after 157 people died in an Ethiopian Airlines 737 Max crash. Emails revealed Boeing bragged about using “Jedi mind tricks” to persuade airlines and regulators that pilots familiar with the earlier version of the 737 would not need simulator training on the Max, a significant cost saving that Boeing knew would appeal to its customers.1 Evidence also indicated that Boeing executives failed to adequately inform pilots about the new system and disregarded engineers’ recommendations for more advanced flight controls.2 In addition, former managers have alleged that Boeing set ambitious cost targets to offset orders placed at prices unattainable from an engineering standpoint.3 A recent FAA inspection confirmed that the 737 Max failed 33 of 89 safety checks.4

Leaders at Boeing and other great companies can succumb to hubris. They lose the discipline necessary to sustain the organization’s competitive advantage, grow too quickly, undertake projects outside of their scope, and commit other blunders. The pattern of these missteps resembles the Israelites’ mistakes after they entered the Promised Land. Prior to entering the Promised Land, time spent in the desert was intended to provide the Israelites with the discipline necessary to learn to trust God. Upon entering a land occupied by people who did not know God, the Israelites began straying from God’s conditions for remaining in the Promised Land. In a similar manner, success can sway organizations to forsake their core values, overreach, and lose their competitive advantage.

This article explores the sequence of poor decision making that leads to decline in successful companies in light of the Israelites’ experience in the Promised Land. The discussion begins with a brief review of Collins’ five stage model of corporate decline, focusing on the mistakes that result as discipline is lost. It then examines how each stage along the path of decline (i.e., Hubris Born of Success, Undisciplined Pursuit of More, Denial of Risk and Peril, Grasping for Salvation, and Capitulation to Irrelevance or Death) has characteristics that also mark the periods of the Israelites’ experience in the Promised Land (i.e., Conquest and Judges, Kingdoms of Saul and David, Solomon’s Reign, the Divided Kingdom, and Exile). The insights gained from this analysis suggest a possible mediating mechanism in the form of a repentance process that can help restore success during organizational decline.

Collin’s Stages of Decline

Conventional wisdom ascribes the failure of many great companies to causes outside of management control, but research suggests otherwise. A study of 500 top corporations over the latter part of the 1900’s examined stall points – sudden and ongoing nosedives in revenue growth.5 The researchers found that if a company was not able to reverse a stall in a couple of years, it was unlikely to resume healthy revenue growth. Their analysis traced stall points to external factors only thirteen percent of the time, with the remaining eighty-seven percent attributable to either strategic factors or organizational design – factors under the control of management. Common strategic missteps included premium position captivity, where a competitor challenged the firm by either lowering costs or changing the consumer’s perception of the product’s value; malfunctions in managing innovation; and failure to capitalize on an existing core’s growth possibilities. A common organizational factor identified in the analysis was a lack of managers and workers able to competently implement a strategic initiative. These four factors accounted for more than half of the stall points that occurred.

In his book How the Mighty Fall, Jim Collins also attributed declines in highly successful businesses to factors within the control of its leaders.6 The four factors cited in the study above appear throughout different stages of Collins’ approach. He deconstructed paths of the decline of eleven successful companies into five stages:7

Stage 1: Hubris Born of Success

Stage 2: Undisciplined Pursuit of More

Stage 3: Denial of Risk and Peril

Stage 4: Grasping for Salvation

Stage 5: Capitulation to Irrelevance or Death

Although failure to innovate or change is often cited as a cause of corporate decline, “overreaching better captures how the mighty fall.”8 According to Collins, arrogance in Stages 1-3 leads to strategic mistakes and slows the organization’s growth trajectory. However, the organization appears to be strong and thriving until Stage 4, where its internal decline becomes apparent to outsiders.

Just as firms can eventually lose the discipline necessary to sustain their competitive advantage when they become successful, the Israelites began straying from God’s conditions for remaining in the Promised Land as soon as they entered it. Prior to their entry into the Promised Land, Moses reminded the Israelites that God’s covenant with them was contingent on their obedience to him (Deut. 7:12-16). Over the previous forty years, God had used the desert to teach them to rely on him, especially during times of uncertainty. The desert had forced the Israelites to depend on God for food, water, and protection. Reliance on God manifested itself as obedience. They followed the cloud/fire in the desert, staying put or moving according to his instruction (Exodus 13:21). In other words, the time the Israelites spent in the desert provided the discipline that they needed as they learned to trust and obey God.

Moses articulated two concerns regarding their future adherence to the covenant. First, he warned the Israelites that times of plenty in the Promised Land could cause them to forget God and his faithfulness to them (Deut. 8:11-14). Second, their stubbornness troubled him: “For I know how rebellious and stiff-necked you are. If you have been rebellious against the Lord while I am still alive and with you, how much more will you rebel after I die!” (Deut. 31:27).9 Telling the Israelites they were stiff-necked was intended to call them out as a people not amenable to being led by God.10

One of the promises included in the covenant was that the blessings promised to Abraham’s descendants would eventually be available to everyone (Genesis 12:2-3).11 Abraham’s descendants were intended to be set apart and serve as an example. Remaining distinct required not blending in with those living in the surrounding countries by adopting their customs and habits. It also meant not forming alliances with people in the area or worshipping idols (Deut. 7:2-3 and Deut. 8:19-20).12

The call for the Israelites to resist becoming indistinct, forgetful, or stubborn provides insights for organizations seeking to cement their competitive advantages. Decision-makers in successful companies understand the source of their distinctiveness – principles or values that set them apart from their competitors. Maintaining a competitive advantage requires the discipline to choose only those actions that align with the company’s core values. Collins argued such discernment requires the understanding of why things are done the way they are done (their processes) and under what circumstances those processes might be changed.

Great companies are disciplined in sustaining their competitive advantage. Jay Barney’s Resource Based View ascribes sustainable competitive advantage to possessing resources that are valuable, rare, and difficult to imitate or substitute.13 In the case of the Israelites, this discipline to sustain a competitive advantage is upheld by God’s command that his people remain distinct and not seek to worship God-substitutes. Yet their forgetfulness once they settled in the Promised Land led to idol worship and other forms of disobedience. Their spiritual separation eventually led to physical dislocation from the exile. The same could happen to enterprises which are disciplined in the initial stages but become lax once a record of success is established.

Stage 1: Hubris Born of Success (the Conquest)

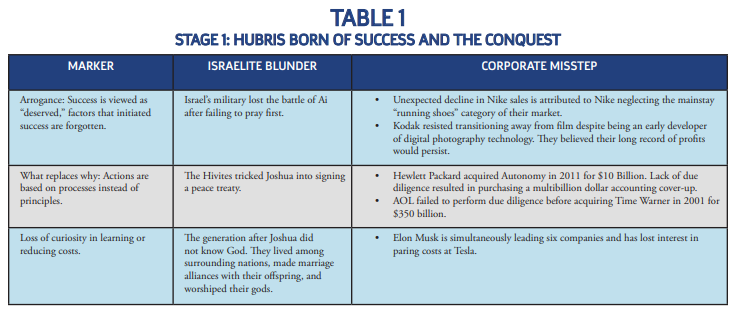

Collins described an organization’s initial stage of decline as “hubris born of success.” Table 1 lists selected characteristics associated with this stage. In this stage, the organization perceives success as deserved and expects it to continue regardless of what it chooses to do. Leaders attribute success to processes, or what the organization does, as opposed to principles – the “why’s” for things done in a specific manner and the circumstances that would make those processes ineffective. A decline in the readiness of the organization to keep learning is evident as leaders become less inquisitive.

The characteristics in Table 1 are apparent soon after Joshua led the Israelites into the Promised Land. Prior successes led Joshua and the military leaders to rely on self-confidence instead of prayer prior to the first battle of Ai, in which they suffered devastating losses (Joshua 7:2-5).14 Being enamored of their previous accomplishments, they expected success in the battle because of their record of victory rather than the true cause of their success – God’s favor on them as a people set apart to trust and obey him. Learning from the defeat at Ai, Joshua and the army won their next battle and had miraculous victories over the Canaanites as they obeyed God.

Joshua 9:3-15 describes another misstep that occurred when Joshua and the leaders formed an alliance with Gibeon, one of the surrounding countries with whom God instructed the Israelites not to make agreements. The Gibeonites were able to mislead Joshua because he failed to seek God’s counsel. The lack of due diligence in the decision-making process reveals the Israelites’ arrogance and expectation of unmitigated success, putting their trust on processes as opposed to principles. In both missteps the Israelites discounted the role of a factor beyond their control – God’s favor, and relied too much on their own capabilities.

Despite these mistakes, Israel prospered, serving God throughout the lifetime of leaders who outlived Joshua (Joshua 8:3-27 and Joshua 24:31). However, the next generations did not know God and refused to obey his laws. Displaying the traits of Stage 1, the new generations became less learning oriented. God sent judges to remind the Israelites of his faithfulness and to guide them, but they stubbornly refused to turn away from their evil practices. Ignoring the instructions in Deuteronomy 7:2-3, they lived among the seven nations, made marriage alliances with their sons and daughters, and worshiped their gods, perpetuating cycles of sin, outside occupation, and peace (Judges 1:1–2:10 and Judges 3:7-11). The last verse of Judges concludes: “In those days Israel had no king; everyone did what as they saw fit” (Judges 21:25). It speaks to the Israelites’ refusal to educate themselves in God’s word.

As with the Israeli experience, there are many parallel corporate examples in this stage. Table 1 lists a few recent instances. An arrogant attitude that renders success as “deserved,” such as what happened at Ai, could describe Nike’s surprising decline in sales recently as it shifted the focus from running, a core business, to limited-edition sneakers.15 The Hivites tricked Joshua into signing a peace treaty after he failed to conduct due diligence because of his arrogance and a focus on process instead of principles. In the same way bad outcomes ensued from AOL’s merger with Time Warner and Hewlett Packard’s acquisition of Autonomy.16 At Tesla, as Elon Musk simultaneously runs SpaceX, The Boring Co., Neuralink, X Corp. and xAI, he has lost interest in reducing costs at the EV company.17 These mistakes happen when decision-making becomes process-oriented instead of principles-based. They are a reminder to leaders of the need to focus on core capabilities, maintain discipline, and continue learning about their businesses and the environment.

Stage 2: The Undisciplined Pursuit of More (the Kingdoms of Saul and David)

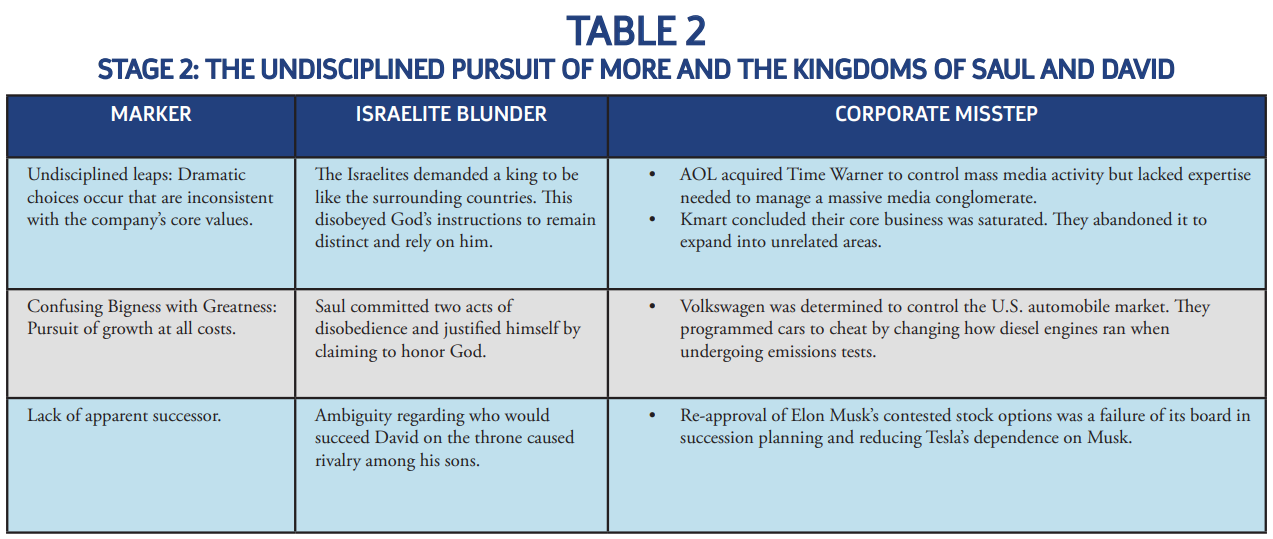

The next stage of decline in Collins’ analysis occurs when the organization pursues more scale and scope to the point of overreach. Table 2 lists selected characteristics associated with this stage. Dramatic changes occur that are inconsistent with the organization’s core values. Previous successes lead to unrealistic growth expectations, creating an obsession that confuses getting bigger with principles that have made it great in the past. Leaders pursue their own self-interests instead of those of the enterprise, allocating more resources for themselves and their inner circle. Long term organizational success is sacrificed for short term gains. Undisciplined growth increases costs, and the organization responds by increasing prices instead of becoming more disciplined. Undisciplined growth results in bureaucratic rules replacing an environment of freedom and responsibility that was associated with discipline. The proportion of right people in key positions declines due to an exodus of talent or growth beyond the organization’s ability to execute competently. Future leadership succession becomes less apparent.

Several characteristics of Stage 2 are apparent in the reigns of Israel’s first two kings. God rescued the Israelites from slavery in Egypt to provide them with the freedom to worship him. Although they were supposed to rely on God for security, the Israelites demanded a king to be like the nations around them and to feel safe (1 Samuel 8:5).18 When Saul was anointed king he succeeded militarily but “his explosive disposition caused trouble more than once with both people and prophet” (1 Samuel 10:23-24).19 Saul’s hubris reflected his insecurity and obsession with his self-image, symptomatic of an attribution bias causing an extreme belief in one’s abilities.20 Consider Saul’s disobedience at Gilgal when he became worried that his army would leave. He sacrificed the animals before battle instead of waiting for Samuel as instructed (1 Samuel 13:7-14). He prioritized enhancing his image over obeying God, pursuing self-promotion at the risk of the organization’s success. He made a second decision that reflected another trait of Stage 2, overreaching. God instructed him to attack the Amalekites and destroy everything for the purpose of a holy war (1 Samuel 15:1-3). After battle he disobeyed and “spared King Agag and the best of the sheep, the oxen, the more valuable animals, the lambs, and everything that was good” to enhance his standing with his own people and offer a sacrifice (1 Samuel 15:9-24). Saul prioritized the process (the sacrifice) over the principle (obedience to God) and was rejected by God as king.

David replaced Saul as king and enjoyed numerous military successes that included victory over the Philistines (2 Samuel 5:4-5).21 Although often described as a man after God’s own heart, David committed missteps emblematic of Stage 2. David placed his own interests ahead of those in his organization. He remained in Jerusalem instead of staying with his troops during the Ammonite war, which led to his adultery and murder of Uriah (2 Samuel 11:1-27). He called for a census for military draft and taxation purposes that was opposed by the Israelites and angered God (2 Samuel 24:1-2).22 Unlike the census taken while the Israelites were in the desert, David’s order was an undisciplined leap that violated a core value of the covenant – relying on God’s provision of adequate resources for security. As a result, David’s rule provided increased protection against external threats but came at the cost of personal freedom for the Israelites as they were expected to join the military.23 He replaced discipline with bureaucracy and a system of rules that eroded freedom and raised cost and taxes.

David’s choices resulted in a lack of clear succession to leadership, another indicator of Stage 2. It is apparent in Scripture (2 Samuel 13:1-18:33) that David’s multiple wives were among those who wondered who David’s successor would be.24 Rivalry among David’s sons induced instability. Absalom murdered David’s oldest son, Amnon, and later died in battle after rebelling against David (2 Samuel 13:20-29, 2 Samuel 15:1-12, and 2 Samuel 17:24-18:33). Adonijah, the oldest surviving son, proclaimed himself king before Nathan and Bathsheba convinced David to select Solomon as king instead (1 Kings 1:5-30).

Table 2 offers a number of corporate examples that illustrate Stage 2 missteps. Israel’s desire to be like other nations led them to abandon their single focus on God as King, a “core” reason for flourishing. In a similar manner AOL acquired Time Warner to diversify from its core business (internet operations), yet it lacked the expertise to manage the massive media conglomerate. Kmart expanded from its core retail operations to a network of unrelated businesses (fast foods, Payless drug stores, Sports Authority, and OfficeMax) that challenged its leadership. Volkswagen cheated on emission tests with built-in software that reflected an “overwhelming desire to dominate the U.S. market with diesel-powered vehicles.”25 In the case of Tesla, the board re-approved founder Elon Musk’s contested stock options and failed to strategically lay out a plan of succession,26 in a way that is reminiscent of David’s failure to execute a succession plan. These examples demonstrate the risk of failing to take advantage of “core” opportunities, adhere to foundational principles of greatness, and execute meaningful succession plans as organizations scale.

Stage 3: Denial of Risk and Peril (Solomon’s Kingdom)

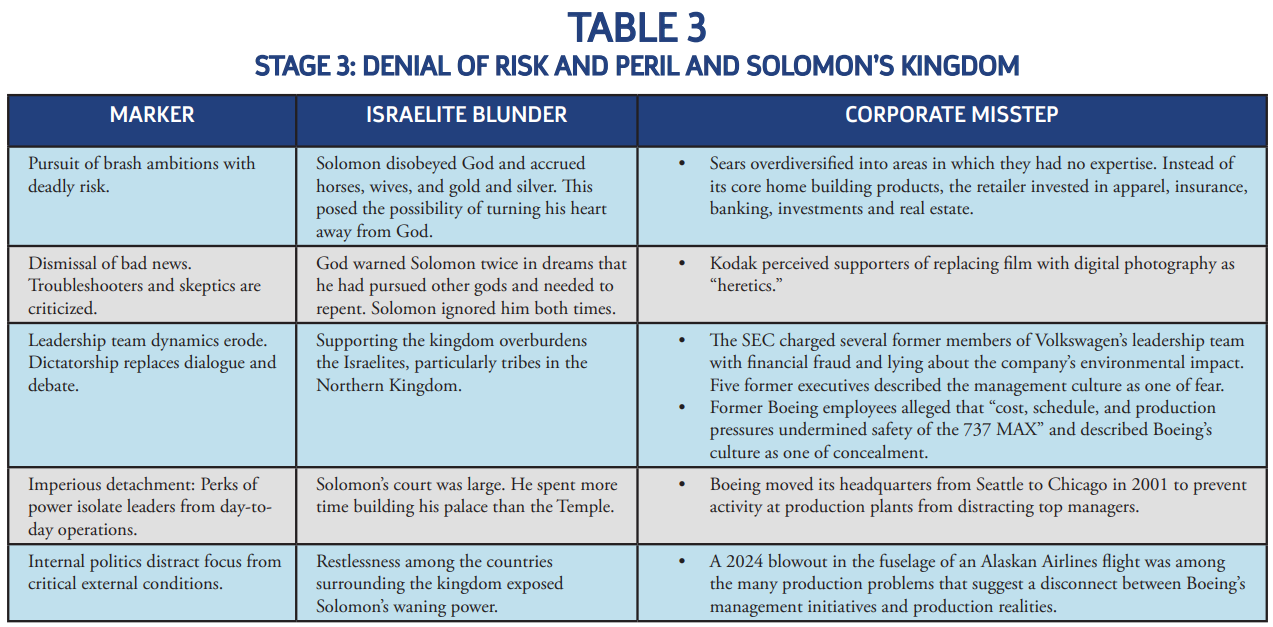

Collins’ third stage of organizational decline is characterized by the denial of risks and perils. Table 3 lists selected characteristics associated with this stage. Mounting arrogance over the previous stages results in a decision-making process that is overly optimistic. Excessively ambitious forecasts of sales, costs, and other metrics ignore production realities and the accrued experience. Over optimism and arrogance are evident – negative news is disregarded, and external praises are embraced. Team dysfunction emerges as the decision-making process regresses from one characterized by debates producing unified decisions to authoritarian pronouncements leading to unhappy detractors. Leadership perks insulate management from day-to-day operations and further contribute to the culture of arrogance. Decision-makers become preoccupied with reorganization and other aspects of internal operations at the expense of remaining informed of crucial external circumstances.

At the beginning of his reign, Solomon asked for wisdom but God gave him wealth and honor as well, on the condition that he continued to obey God (1 Kings 3:4-14). Despite such promising beginnings, Solomon subsequently made other disastrous decisions. He succumbed to the endowment effect, a tendency to overvalue possessions. He made choices that were prohibited: many horses, multiple wives, and stockpiles of silver and gold.27 Solomon’s foreign wives led him to build “high places” for worshipping their own false gods (1 Kings 11:1-10). God admonished Solomon twice in dreams about his transgressions but he ignored them, exhibiting a confirmation bias where one chooses to ignore unfavorable information and favor information that is consistent with currently held values and beliefs.

Before granting the Israelites’ request for a king, God had warned that their sons, daughters, and money would be taken to support a kingdom (1 Samuel 8:11–17). Erosion of healthy team dynamics, a characteristic of Stage 3, was apparent as people in the kingdom became overburdened from supporting Solomon’s kingdom, particularly the northern tribes.28 Solomon eventually drafted workers from the southern tribes, angering that portion of the kingdom as well.29

In Solomon’s quest for more (the “imperious detachment” characteristic of Stage 3), he embarked on grandiose projects including the Temple and his palace, which took six more years to complete than the Temple (1 Kings 6:36 and 1 Kings 7:1). He also had a large court (1 Kings 4).30 Resentment among the Israelites increased as they realized that they were being exploited for Solomon’s enrichment rather than for national welfare.31

The spending needed to support multiple wives, lavish building projects, and a growing bureaucracy forced Solomon to sell territory, causing him “to lose control of strategic routes.”32 This confirms another sign of Stage 3: a leader who becomes distracted by internal politics would pay less attention to strategic external conditions. Growing restlessness in surrounding countries testified to Solomon’s waning power.33 Hadad led a revolt in Edom and became an adversary of Solomon by interrupting trade routes and attacking his kingdom (1 Kings 11:14-22). Additional headaches for Solomon occurred after Rezon took over Damascus and weakened Solomon’s ability to control Aramean territories (1 Kings 11:23-25).

Some corporate examples are illustrative of Stage 3. Sears’ overly ambitious diversification into clothing, banking, investments, and real estate outside of its core retail business contributed to its ultimate downfall. Kodak dismissed the threatening “bad news” of digital photography as “heretic.”34 Just as erosion in leadership trust ensued from the overburdened Israelites, employees at Volkswagen and Boeing described their corporate cultures as ones of fear and concealment.35 Boeing’s management decided in 2001 to move its headquarters from Seattle to Chicago so that senior executives would not be distracted by its production plants.36 A recent blowout in the fuselage during an Alaskan Airlines flight has been attributed to “manufacturing error or lack of quality control” and is among the production problems that indicate a disconnect between Boeing’s top-level initiatives and production realities.37 Aside from imperious detachment, these production problems also reflected a preoccupation with internal politics at the expense of a focus on external conditions, which is reminiscent of Solomon’s problems as neighboring countries became restless.

The denial of risk and peril apparent throughout Solomon’s reign is a sober warning of how easily downfall can happen, despite extraordinary beginnings. Arrogance hampers an organization’s ability to recognize downside risks. Solomon’s leadership fails serve as a reminder of the dangers of dismissing bad news, detachment from the needs of the rank and file, and allowing internal politics to overshadow external circumstances.

Stage 4: Grasping for Salvation (The Divided Kingdom)

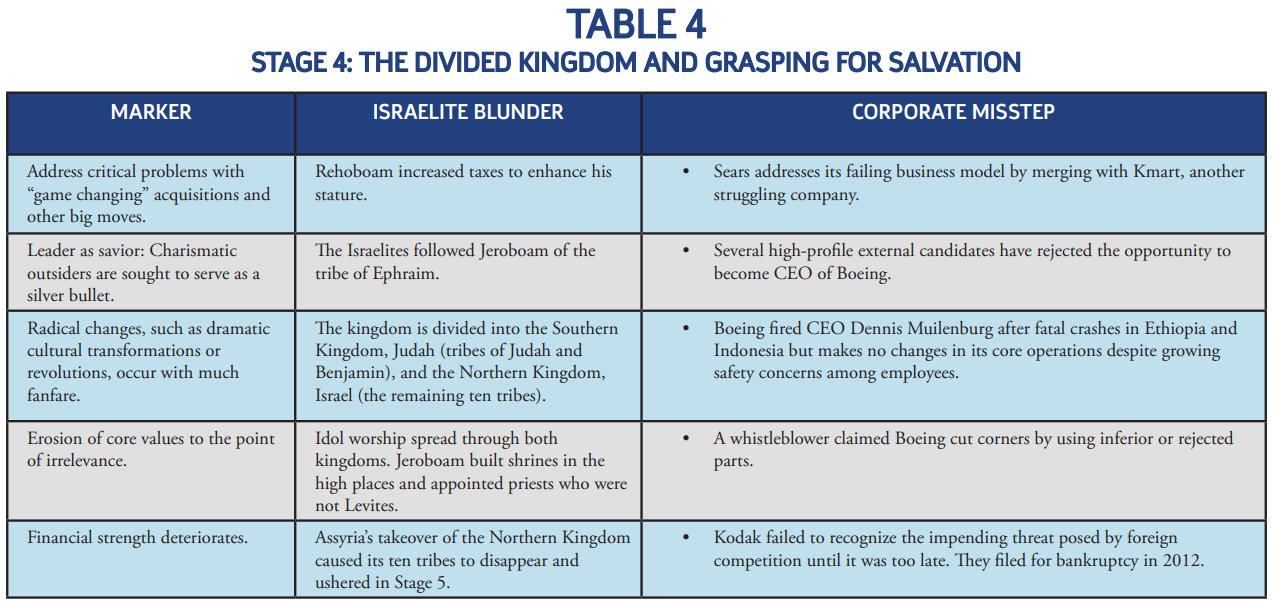

Ongoing internal deterioration becomes apparent to outsiders as the organization grasps for salvation in Stage 4. Table 4 lists some characteristics associated with this stage. The organization frantically searches for “game changing” acquisitions, exciting innovations, or other silver bullet solutions that are inconsistent with its core values or competency. Desperation also causes it to seek a charismatic leader-as-savior, often an outsider. The culture becomes obsessed with a highly publicized radical change or transformation. Members become confused or cynical as the organization drifts further away from its core values. Decreased cash flows and financial distress force repeated organizational restructuring and further narrow its range of choices and strategic options. Temporary improvements are followed by letdowns.

An important point emphasized in Collins’ analysis is that despite issues hampering internal processes in Stages 1-3, the organization appears to be healthy and thriving to outsiders. Similar impressions apply to the Promised Land at this point in history. The reigns of David and Solomon are often described as the “Golden Era.”38 The northern and southern tribes were strong militarily and economically, enjoying “unprecedented wealth and fame.”39

The internal decline of the kingdom became visible after Solomon’s death when his son Rehoboam became king, pushing the kingdom into Stage 4. The high taxation necessary to support the kingdom had provoked growing public resentment. When the Israelites asked Rehoboam to lower taxes, he took advice from his young advisors (and ignored his elder advisors) to toughen his image by making the “big move” of further increasing the tax burden (I Kings 12:7-14). Consistent with Collins’ prediction that “big moves” are more likely to occur when a manager succeeds a legendary leader, Rehoboam intended the move to elevate his image above Solomon. In response, the northern tribes rebelled. Like desperate firms that find themselves in Stage 4, the breakaway tribes sought a silver bullet – they gravitated toward an outside leader, Jeroboam of the tribe of Ephraim.

Upon establishment of the divided kingdom (The Southern Kingdom of Judah led by Rehoboam and the Northern Kingdom of Israel led by Jeroboam),40 the trust of God gave way to idol worship in Israel, reducing core values to the point of irrelevance (another trait of Stage 4). Jeroboam permitted this violation of God’s law to protect his leadership and to discourage the people from going to the Temple in Jerusalem (I Kings 12:26-27). He also built shrines in high places and appointed priests who were not Levites (1 Kings 12:31-35).

Chronic restructuring and erosion of financial strength, another trait of Stage 4, became evident in both Judah and Israel. Egypt plundered the Temple and the King’s palace, decreasing the Southern Kingdom’s financial strength (I Kings 14:25-26). Assyria took over the Northern Kingdom, a “restructuring” that caused the ten tribes to disappear, pushing that part of the Promised Land into Stage 5 – the capitulation to death (2 Kings 17:23).41

Upswings and disappointments, a Stage 4 trait, characterized much of the Southern Kingdom. Attempts to lead the kingdom in an obedient manner were apparent throughout Asa’s 41-year reign as he eliminated prostitutes and idols and returned silver and gold to the Temple (1 Kings 15:1-15). King Hezekiah’s 29-year rule was another upturn. He “reestablished worship” in the Temple after cleansing it, removed high places and idols in Judah, and reinstated Passover (2 Kings 18:1–5, 2 Chronicles 29:1–36, and 2 Chronicles 30:1–27). Later in his reign, he became mortally ill but God spared his life. Once healed, Hezekiah boasted of Judah’s wealth to the Babylonians. Interestingly he actually found comfort in Isaiah’s warning about the future invasion of the Babylonians (Micah 3:12) because it would not have occurred during his lifetime (a trait harkened back to Stage 3’s “Denial of Risk and Peril”).42 Hezekiah chose personal comfort and safety at the cost of security for his kingdom.43

After Hezekiah’s death, his son Manasseh allowed Judah to return to idolatry, restore the high places, and practice sorcery (2 Kings 21:1–9 and 2 Chronicles 33:1–9). The last righteous ruler of Judah was Josiah, who reigned for 31 years. He tried to eliminate idolatry in Judah, oversaw repair of the Temple, and rediscovered the Book of the Law.44 His reign was followed by kings who disobeyed God and oversaw a suffering kingdom.45

Table 4 offers a few corporate examples illustrative of Stage 4 malaise. Much like Rehoboam’s bold move to raise taxes, Sears made the “game changing” decision to merge with Kmart, another failing company.46 While the ten northern tribes sought in Jeroboam an outside savior,47 Boeing sought a new “savior” external candidate as CEO including former executives from GE and Carrier Global.48 The radical transformation of the unified Israel Kingdom into North and South echoed Boeing’s 2023 claim that it transformed its culture to one more tolerant of dissent. More recently, claims have emerged that Boeing was cutting corners by using nonconforming and inferior parts.49 If true, they confirm that core values in this once stellar manufacturer have eroded to the point of irrelevance, much like the return of idol worship in the Promised Land. The Northern Kingdom’s demise after it was taken over by Assyria also reminds us of Kodak’s bankruptcy after it ignored the threat posed by foreign competition.50

Much can be learned from these experiences. Leaders are well advised to resist “big moves” to enhance the organization’s image or as a panacea for problems. Outside candidates need not be sought as a natural in leadership succession plans. Most importantly, organizations must not allow the pressure of a desperate situation to promote choices that compromise core values. Just as external factors failed to pose serious threats to the divided kingdom until they were well into Stage 4, businesses could very well survive external threats (e.g., innovation or structural shocks) unless they had progressed through deterioration in values and competence during the beginning stages of decline.

Stage 5: Capitulation to Death vs Restoration (the Exile)

When distinguishing organizations in Stage 4 that capitulate to death from those that eventually bounce back, Collins identifies two factors. First, spending more time in Stage 4 increases the odds that an organization will fail as its financial strength and morale wear away. Failed companies lack liquidity and the ability to repay debt.51 Second, although no single leader can build an organization, the wrong leader with power can bring it down. Research shows that ethical failures, when key leaders operating with malicious intent, characterize some of the most spectacular business failures over the past twenty-five years.52 Research also shows that leaders evaluated as having “high character” generate a return on assets (ROA) that is five times of those evaluated as “low character.”53 Consider this in the context of Solomon’s decision to marry multiple foreign wives. The alliances that ensured access to resources came at the cost of violating God’s mandates and destroyed Solomon’s faith and his ability to uphold God’s law. 1 John 2:15-17 remind us that:

Do not love the world or anything in the world. If anyone loves the world, love for the Father is not in them. For everything in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life—comes not from the Father but from the world. The world and its desires pass away, but whoever does the will of God lives forever.

Solomon’s love for women and wealth reflects priorities that are world-centric instead of God-centric. If he had an eternity perspective and prioritized choices with long term spiritual benefits, the outcome for him and his kingdom could have been very different.54

The Northern and Southern kingdoms show the divergence in paths possible once companies enter Stage 4. Twenty monarchs (and nine different dynasties) ruled the Northern Kingdom between its beginning and its destruction by the Assyrians, and Scripture describes them all as evil.55 Despite warnings sent by God through his prophets, the Northern Kingdom never repented. It entered Stage 5 and capitulated to death when its tribes completely disappeared. Many organizations also find themselves irrelevant or dead subsequent to the deterioration of morale and finance during previous stages of decline. In contrast, the Southern Kingdom underwent periods of occupation, exile, and restoration. In the same way some companies experience ups and downs in Stage 4 but eventually regain success.

Exile serves an important role in both kingdoms. God physically transplanted the Israelites to a spiritual situation that was apart from God.56 Jeremiah warned the Northern tribes that they needed to repent, but they ignored him (Jeremiah 7:5-8). Although God disciplined the Israelites, his ultimate purpose of exile was restoration.57 When King Cyrus of Persia allowed the Israelites to return to Jerusalem, some chose to stay in Persia and be spiritually separated from God. The choice to return to Jerusalem and reconstruct the Temple required conversion, a more challenging commitment than staying put.58

Great companies can also decide to stay put. Kodak enjoyed a long tradition of success that shielded it from market changes impacting its competitors.59 This prevented Kodak from recognizing the crisis at hand until they were in Stage 5. God sent prophets to remind the people of what he had said and to call for them to repent. Reversing organizational decline requires developing a process of repentance as well.

A Process of Repentance

What would a process of repentance look like in the context of corporate decline? The arrogance apparent in many characteristics throughout this analysis stems from cognitive biases. The stubbornness of the Israelites in response to God’s admonitions and companies in response to warnings regarding unrealistic goals and targets reflects confirmation and optimism biases. These biases describe a tendency to favor information that is consistent with current beliefs, and a tendency to underestimate the likelihood of negative events and overestimate the likelihood of positive events. Proximity bias, a tendency to favor whoever and whatever is closest, describes problems stemming from succession planning and imperious detachment as in the kingdoms of David and Saul, and perhaps at Tesla as a modern-day example.

Attribution bias, the tendency to ascribe positive outcomes to personal ability and negative outcomes to outside circumstances, is characteristic of Saul’s acts of disobedience.60 The Dunning-Kruger effect that occurs when people with limited expertise overestimate their abilities, is apparent when the Hivites duped Joshua into signing a peace treaty. HP’s acquisition of Autonomy and AOL’s Time Warner merger are possible victims to such biases on the part of the leadership as well.

A repentance process involving introspection and re-examining and guarding core values and principles provides a useful way to counter biases. The process needs to test the accuracy of views embedded in strategic assumptions, which must be made explicit. One way to challenge optimism and confirmation biases is to form a “core-belief identification team” that identifies the organization’s most “deeply held” assumptions/principles rather than relying on conventional wisdom in the executive suite.61 Problems posed by the Dunning-Kruger effect and the attribution bias can be mitigated by forcing leaders to more thoroughly consider implications of strategic assumptions. One approach that has proven successful is to have decision-makers imagine implementing a particular strategic initiative and write an autopsy of it one year into the future after it fails.62 To avoid succession planning and other issues associated with proximity bias, organizations can identify talented employees, form a shadow cabinet, and have them attend executive meetings on a rotational basis.63

The effectiveness of a repentance process will be influenced by the culture where strategic assumptions and decisions reside. Former employees at Boeing and Volkswagen have described their corporate culture as ones of concealment and fear. In Google’s study of what makes a team function well, it identified psychological safety, an environment where an organization’s members are comfortable sharing questions and concerns, as being most important.64 In this context, organizations must strive to find the appropriate balance between psychological safety and accountability.65 Psychological safety must also apply to those who are willing to admit mistakes, and they are more likely to do so if their leader does the same. Finally, in analyzing failures, it is more effective in identifying the process that led to the failure rather than finger pointing the immediate cause.66

Conclusion

Successful firms that decline follow stages that also describe the experience of the Israelites after they entered the Promised Land. The Israelite’ experience offers a number of strategic insights for businesses. These include reminders for leaders to exploit opportunities within their core values and competence, distinguish principles from processes, and continue learning about their business. Mistakes committed by Saul and David emphasize the importance of adhering to core principles, not confusing growth at all costs with greatness, and keeping the organization’s interests ahead of those in the leadership. Many of the failures associated with Solomon’s reign stemmed from an arrogance that compromised his ability to recognize choices with significant downside risks. Other revealing mistakes he made include dismissing bad news, detaching from the rank and file, and allowing internal politics to distract his attention from external circumstances. Desperation during the divided kingdom culminated in the Northern tribes selecting an outside leader in a grasp for salvation, but their subsequent struggles warn of the downsides of such “leader as savior” and “big move” strategies.

One of the most important insights from the Promised Land experience is to not allow a desperate situation to force a compromise of core values and principles. Consider Boeing’s 1997 merger with McDonnell Douglas, when it intended to expand into the military market. Collins observed:

If in fact there’s a reverse takeover, with the McDonnell ethos permeating Boeing, then Boeing is doomed to mediocrity. There’s one thing that made Boeing really great all the way along. They always understood that they were an engineering-driven company, not a financially driven company. If they’re no longer honoring that as their central mission, then over time they’ll just become another company.67

The Promised Land experience analyzed in this article can offer a roadmap for Boeing and other businesses that have experienced failures. Life’s questions can be clearly framed and viewed through the “corrective lens of Scripture.”68 In addition, although this article applies the Scriptural framework to corporate decline, the same experience can be profitably applied to circumstances affecting other institutions, including the fall of democracies and economies.

About the Author

Dr. Cora Barnhart is an associate professor of economics at Palm Beach Atlantic University in Palm Beach, FL. Her current research interests include the dynamics of creative destruction and innovation on the economy and applications of faith in business practices. Prior to teaching at Palm Beach Atlantic University, she served as the editor of the Tax section of the Bankrate Monitor and was a visiting scholar with the Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta. She has written several tax and personal finance articles published on websites that include Bankrate, Yahoo, and USA Today. Her academic publications include articles in the Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, Organizational Dynamics, Christian Business Review, Christian Business Academy Review, Economic Inquiry, Journal of Biblical Perspectives in Leadership, Public Choice, The Journal of Futures Markets, and Financial Practice and Education.

Notes

1Peter Robison, Flying Blind: The 737 Max Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing (New York: Doubleday, 2021).

2 Ibid.

3 Jonathan Smart, Zsolt Berend, Myles Ogilvie, and Simon Rohrer, Sooner Safer Happier: Antipatterns and Patterns for Business Agility (Melbourne, Florida: IT Revolution Press, 2022).

4 Peter Georgescu, “Boeing’s Last Chance: Meaningful Purpose, Powerful Culture, Enlightened Leadership,” Forbes, April 30, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/petergeorgescu/2024/04/30/boeingslast-chance-meaningful-purpose-powerful-culture-enlightenedleadership/

5 Matthew Olson, Derek van Bever, and Seth Verry, “When Growth Stalls,” Harvard Business Review 86, no. 3 (2008): 50-61. https://hbr.org/2008/03/when-growth-stalls

6 Jim Collins, How the Mighty Fall (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2009).

7 Ibid, 20.

8 Ibid, 21. For an interesting counterview, see Clayton Christensen, The Innovators Dilemma (New York: HarperBusiness, 2011). He focuses on failure in previously successful companies occurring because a business method they have relied upon suddenly becomes outmoded.

9 Oxen that were stubborn or difficult to guide when pulling a plow were described as stiff-necked.

10 https://www.internationalstandardbible.com/S/stiff-necked.html

11 See John Piper, “The Covenant of Abraham” Desiring God, October 18, 1981. https://www.desiringgod.org/messages/thecovenant-of-abraham.

12Romans 2:12 is among many reminders in the New Testament that make it clear that Christians should remain distinct and not conform to the world.

13See Jay Barney, “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage,” Journal of Management 17, no. 1 (1991): 99-120. He also makes the case that difficulty in substitutability requires the resource to satisfy at least one of three conditions: acquired due to unique historical conditions, linked ambiguously to the resulting competitive advantage, and/or possessed a socially complex nature.

14Note that Joshua made a similar error when he agreed to make a covenant with the Gibeonites without praying first (Joshua 9:3-15).

15Inti Pacheco, “Nike Misses the Boom in Running,” The Wall Street Journal, June 28, 2024, B1-B2. Similarly, Kodak resisted transitioning from film despite being an early developer of digital photography technology as leaders refused to believe that their long record of profits would stop. See Richard Randall, “Kodak’s Failure to Exploit its Digital Edge is a Lesson on Complacency,” Central Penn Business Journal 27, no. 42 (2011): 15. http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/trade-journals/kodaks-failure-exploit-digitaledge-is-lesson-on/docview/903809989/se-2. See also Theodore Kinni, “Rita Gunther McGrath on the End of Competitive Advantage,” Strategy+business, February 17, 2014, https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00239.

16Peter Sayer, “The HP-Autonomy Lawsuit: Timeline of an M&A Disaster,” CIO, June 7, 2024, https://www.cio.com/article/304397/the-hp-autonomy-lawsuit-timeline-of-an-ma-disaster.html.

17See Steve Wilm, “Tesla Can’t Be All About Elon Musk,” The Wall Street Journal, June 14, 2024, B12. See also Lora Kolodny, “Elon Musk Wants Tesla to Invest $5 billion into His Newest Startup, xAI — if Shareholders Approve.” https://www.cnbc.com/2024/07/24/elon-musk-wants-tesla-to-invest-5-billion-into-his-newest-startupxai-if-shareholders-approve.html.

18See Alva McClain, The Greatness of the Kingdom: An Inductive Study of the Kingdom of God (Winona Lake, Indiana: BMH Books, 2001): 110. McClain argues the Israelites’ mistake is not their request for a king, but rather asking for a king like other nations. They eventually had a king like those who reigned over other nations and had many wives, great wealth, and other benefits that came at the Israelites’ expense.

19Also see William Sanford Lasor, David Allan Hubbard, and Frederic William Bush, Old Testament Survey: The Message, Form and Background of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1991), 138.

20For more about Saul’s struggle with his self-image, see Garrett Lane Cohee and Samuel Voorhies, “The Impact of Self Deception on Leadership Effectiveness,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business 24, no. 1 (2021): 5-15. https://doi.org/10.69492/jbib. v24i1.589

21For more details concerning David’s victories, see 2 Samuel 8:1-18.

22Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, Old Testament Survey, 248.

23Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, 248.

24Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, 251.

25“Exhausted by Scandal: ‘Dieselgate’ Continues to Haunt

Volkswagen,” Knowledge at Wharton, March 19, 2019, https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/podcast/knowledge-at-whartonpodcast/volkswagen-diesel-scandal/.

26Wilm (2024), B12.

271 Kings 10:21: “All of King Solomon’s drinking vessels were of gold, and all the vessels of the House of the Forest of Lebanon were of pure gold;” 1 Kings 10:26: “And Solomon gathered together chariots and horsemen. He had 1,400 chariots and 12,000 horsemen;” 1 Kings 11:3: “He had 700 wives, princesses, and 300 concubines.”

28Wayne Brindle, “The Causes of the Division of Israel’s Kingdom,” SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 76, no. 1 (1984):223-233. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/76

29See Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, Old Testament Survey, 254; Brindle, “The Causes of the Division of Israel’s Kingdom,” 229; and 2 Kings 5:13-18.

30Brindle, “The Causes of the Division of Israel’s Kingdom,” 223.

31Brindle, 229.

32Ibid, 229.

33See Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, Old Testament Survey, 256; and Brindle, “The Causes of the Division of Israel’s Kingdom,” 227.

34Richard Randall, “Kodak’s Failure to Exploit its Digital Edge is a Lesson on Complacency.” Central Penn Business Journal 27, no. 42 (2011): 15. http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/trade-journals/kodaks-failure-exploit-digital-edge-is-lessonon/docview/903809989/se-2. See also Theodore Kinni, “Rita Gunther McGrath on the End of Competitive Advantage,” Strategy+business, February 17, 2014, https://www.strategybusiness.com/article/00239.

35For more about Volkswagen’s culture see “Fear and Respect: VW’s Culture under Winterkorn,” CNBC, October 11, 2015, https://www.cnbc.com/2015/10/11/emissions-scandal-vws-demandingculture-under-winterkorn-led-to-crisis.html. For more about Boeing’s culture, see Jonathan Smart, Myles Ogilvie, Zsolt Berend, and Simon Rohrer, Sooner Safer Happier.

36See Steven R. Strahler, “Did Relocating to Chicago Help Boeing or Hurt It? The Move was Based on the Professed Need to Buffer Top Execs from the Distraction of the Production Plants,” Crain’s Chicago Business 47, no. 6 (2024): 1. http://search.proquest.com.proxy.pba.edu/trade-journals/did-relocating-chicago-helpboeing-hurt/docview/2926689948/se-2. Note that Boeing moved its headquarters to Arlington in 2023 and is currently debating a return to Seattle.

37Ibid.

38See Lasor, Hubbard, and Bush, Old Testament Survey, 244.

39Ibid.

40Brindle, “The Causes of the Division of Israel’s Kingdom,” 232.

41Note that the Northern Kingdom had also worshipped idols (I Kings 14:22-24) before it was eventually attacked.

42Although this marker is associated with Stage 3, it occurs in Stage 4. Collins indicates these markers may occur in different stages.

43Ernest P. Liang, “Modern Finance Through the Eye of Faith: Application of Financial Economics to the Scripture,” Christian Business Academy Review 7, no. 1 (2012): 69-75. https://doi.org/10.69492/cbar.v7i0.56.

44These events are detailed 2 Chronicles 34:3-21, including discovery of the Book of the Law after it had disappeared.

45Twelve of the twenty rulers in Judah are described as evil. See “Week 25: Southern Kingdom,” THE BIBLE INITIATIVE, accessed July 8, 2024, https://www.thebibleinitiative.com/southern-kingdom. See also Michal Hunt, “The Davidic Kings of Judah 930 – 30AD to Eternity, Agape Bible Study,” 2016, accessed July 23, 2024, https://www.agapebiblestudy.com/charts/Chart%20of%20the%20Kings%20of%20Judah.htm.

46Lauren Thomas and Lauren Hirsch, “Here Are 5 Things Sears Got Wrong That Sped Its Fall,” CNBC, October 12, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/10/11/here-are-5-things-sears-got-wrongthat-sped-its-fall.html.

471 Kings 12:1-24

48Emily Glazer and Sharon Terlep, “Many Balk at Chance to Pilot Boeing,” Wall Street Journal, June 18, 2024, p. B1-B2.

49Clara McMichael, “Boeing CEO Apologizes to Families of Plane Crash Victims before Senate Grilling,” ABC News, June 19, 2024, https://abcnews.go.com/US/boeing-whistleblower-steps-forwardahead-ceos-testimony-washington/story?id=111206197.

50Matthew Olson, Derek van Bever, and Seth Verry, “When Growth Stalls.”

51See James Schaap and Jonathan Breiter, “Ten Reasons Why Companies Keep Failing—An Update”. Working Paper; S.

Bhandari, “Two Discriminant Analysis Models of Predicting Business Failure: A Contrast of the Most Recent with the First

Model,” American Journal of Management 14, no. 3 (2014): 11-19; and S. Bhandari and R. Iyer, “Predicting Business Failure Using Cash Flow Statement-based Measures,” Managerial Finance 39, no. 7 (2013): 667-676.

52G. Rossy, “Five Questions for Addressing Ethical Dilemmas,” Strategy & Leadership 39, no. 6 (2011): 35-42.

53Leaders are evaluated on characteristics including integrity, forgiveness, responsibility, and compassion. See James Schaap and Jonathan Breiter, “Ten Reasons Why Companies Keep Failing—An Update” (working paper) and Mary Crossan, William Furlong, and Robert Austin, “Make Leader Character Your Competitive Edge,” MIT Sloan Management Review 64, no. 1 (2022): 1-12.

54This is one of many helpful insights offered by the referees.

55See https://www.esv.org/resources/esv-global-study-bible/chart-11-02/.

56“The Bible in a Year Study Guide – Era 8: Exile.” Their enemies included the Egyptians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greece, and Rome.

57Ibid.

58Ibid.

59Matthew Olson, Derek van Bever, and Seth Verry, “When Growth Stalls.”

60Examples in the New Testament include the debate among the early Christians regarding whether dietary restrictions and circumcision were required for salvation (Acts 15).

61Matthew Olson, Derek van Bever, and Seth Verry, “When GrowthStalls.”

62Ibid., Pre-mortem analysis is described in D.J. Mitchell, J.E. Russo, and N. Pennington, “Back to the Future: Temporal Perspective in the Explanation of events,” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 2, no. 1(1989): 25–38; and Garrett Lane Cohee and Cora M. Barnhart, “Often Wrong, Never in Doubt: Mitigating Leadership Overconfidence in Decision-making, Organizational Dynamics 53, no. 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2023.101011

63Matthew Olson, Derek van Bever, and Seth Verry, “When Growth Stalls.”

64Isabel Berwick and Brooke Masters, “Why Successful Companies Need to Be Good at Failure,” Working It Podcast (October 9 2023). https://www.ft.com/content/c2c2529e-9829-4484-bc25-1ab51888408b

65Note that David could not repent until he confessed that he had sinned. (2 Samuel 12 and Psalm 51).

66Danny Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow (New York: Farrar,Straus and Giroux, 2011).

67Jon Smart, “Lack of Psychological Safety at Boeing,” IT Revolution (January 28, 2021). https://itrevolution.com/articles/lack-ofpsychological-safety-at-boeing/

68Albert Wolters, Creation Regained: Biblical Basics for a Reformational Worldview (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans

Publishing Company, 2005): 96.