By: Richard H. Jonsen

ABSTRACT

Christian historian R. H. Tawney’s book, The Acquisitive Society, was published in 1920 as Britain and the world emerged from the human tragedy and economic disruption that followed World War I and the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic. Tawney sought to influence the direction of reconstruction in the United Kingdom, arguing for an alternative path for business—serving the common good—as opposed to building personal wealth. This article examines Tawney’s functional society and contemporary common good conceptions of business for application in our emerging post-pandemic context. Several examples of businesses serving the common good are explored, and a framework for transitioning toward common good business practices is offered.

INTRODUCTION

Disruptions in our economic lives predictably result in periods of reflection about the causes of the turmoil and what we can do to avoid similar troubles in the future. A discussion of the need for accounting rules reform following the collapse of Enron, Worldcom, and other high-profile companies in the early years of this century prompted federal legislation imposing those rules.1 The financial collapse of 2008 and the resulting great recession amplified and accelerated the need for rethinking management in the twenty-first century.2 As we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, our current circumstance has prompted the same: witness this volume of Christian Business Review.

One hundred years ago, R. H. Tawney, a historian, scholar, and Anglican follower of Jesus, participated in a similar discussion through his book The Acquisitive Society.3 As the United Kingdom was emerging from the economic disruption and human tragedy of World War I and the 1918-1920 influenza pandemic, Tawney argued for an alternative path for business—serving the common good—instead of the one trodden before the war that focused on building personal wealth. Our American circumstance in 2021 is by many measures not as severe as that faced by Britain on the heels of World War I. Yet, the combination of our twenty-first century pandemic, heightened racial and political strife, and continuing disruption of our natural environment have spotlighted social, economic, and environmental systems that are not working for many of our fellow citizens, all of whom bear the image of God. Like our twentieth-century British counterparts, we face a choice of how to proceed into the century unfolding before us. Will we choose to return to our pre-pandemic “normal” or take this opportunity to change our business design and practice to address the social, economic, and environment-related difficulties experienced by many of our fellow image-bearers?

THE ACQUISITIVE SOCIETY

R.H. Tawney was an early critic of what we commonly refer to today as shareholder primacy: management’s primary duty is to build shareholder wealth.4 He viewed shareholder primacy as a fundamental flaw of business and industry rooted in Western individualism.5 This individualism resulted in what Tawney described as the “acquisitive society,” one in which the “whole tendency and interest and preoccupation is to promote the acquisition of wealth.”6 He contrasted this with a “functional society” in which businesses and industries serve a social function or purpose. In a functional society, the purpose of business is to supply humanity with goods and services that are “necessary, useful, or beautiful, and thus bring life to body or spirit.”7 Tawney credited humanity with recognizing the social role of economic activity from time to time and celebrated activities that result from this recognition. He mourned, however, the generally short-lived nature of these activities that predictably succumbed to the forces of individualism, greed, and wealth-building.

Tawney’s primary concern in The Acquisitive Society was to examine and challenge shareholder primacy and resolve industrial strife in Britain. His narrative traced the development of acquisitive societies in history and argued for creating purposeful institutions characteristic of a functional society. The key to emerging from the rubble of World War I and the influenza pandemic was understanding the purpose of industry from the proper perspective. That perspective views economic interests as but one aspect of life. It encourages citizens to put aside opportunities for wealth building that do not bring life by being necessary, useful, or beautiful; a proper view of industry subordinates wealth building to meeting social needs by recognizing business as “the servant, not the master, of society.”8

It is important to note here that Tawney understood capital and profit as necessary; its purpose and deployment were his points of concern. He drew distinctions between capital invested and profits taken by entrepreneur owners/ managers who were actively involved in a business versus shareholders who had no interest in a company other than profiting from their investment. Tawney was also a product of his time. He was a socialist who served on a commission that recommended coal industry nationalization (which Parliament did not implement). However, we must be careful not to dismiss Tawney’s observations and perspective because of his advocated solutions. Tawney himself recognized that time and circumstances change, and as such, so do potential solutions. He viewed his writings as contextual or topical, as platforms from which to measure changes in society over time. And as societies and their problems evolve, so will their potential solutions.9

THE FUNCTIONAL SOCIETY AND HUMAN FLOURISHING

Dawney’s reflections on the potential for a functional society in which wealth serves the interests and needs of society rather than simply increasing shareholder prosperity were deeply rooted in his understanding of Jesus as God Incarnate.10 The incarnation and the Trinity were foundational to Tawney’s belief in equality and human dignity. This belief had implications for industry and society. Equality was the foundation for order, authority, and justice: “a belief in equality means that… nothing can justify my use of power which chance gives me (the chance of a majority as well as wealth or birth) to the full, that nothing can justify my using my neighbor as a tool, or treating him as something negligible which may be swept aside to realize my ends, however noble those ends may be.”11

Tawney’s understanding of the value of the human per- son, relationships between persons, and justice are consistent with the biblical concept of shalom. The Hebrew word shalom and Greek word eirene are commonly translated into English as peace. But shalom has a much broader and deeper meaning in the Hebrew Bible that also applies to eirene in the New Testament.12 Shalom encompasses completeness, fulfillment, individual and relational wholeness, community, harmony, tranquility, friendship, and prosperity.13 Nicholas Wolterstorff describes shalom as the human person living in peace with, and enjoying or delighting in relationships with God, self, others, and nature.14 A more representative translation of shalom into English may be “wellbeing in every dimension of life,”15 or flourishing: the full development of the God-given design and potential in all persons.16 Importantly, shalom or flourishing is only realized in the context of justice. Shalom “is the real presence and fruition of divinely created design and intention in the created order” and “requires objectively realized justice.”17 Shalom cannot be achieved by simply persuading people they are happy or content in their situation.

Tawney’s purpose of business in a functional society—to supply humanity with goods and services that are “necessary, useful, or beautiful, and thus bring life to body or spirit”18 —is a conception of business that honors and promotes human flourishing both inside and outside the organization. This is similar to the “common good” theme found in many contemporary Christian examinations of the purpose of business.19 The common good purpose of business recognizes humanity as created in the image of God. As such, each person has inherent dignity and worth and is made for relationship. Further, each person is inherently creative and has been called by the Creator to partner with him in stewarding his physical and social creation.20 This stewardship requires work, which as a part of God’s good created order, also has inherent value. The common good purpose of business is to partner in God’s mission of redemption by creating for-profit workplace communities that produce goods and services which promote human flourishing inside and outside the organization. This includes providing meaningful, creative work, facilitating the healing of economic relationships throughout the supply chain, and giving voice to the marginalized.21

Tawney’s functional society sought social and individual wellbeing or human flourishing, and he understood the vital role business and industry played in realizing human flourishing. While the specific solutions he proposed in his time are unlikely to gain traction in the early twenty-first century United States, his aspirations as a follower of Jesus remain relevant today; indeed, they have been similarly articulated by our contemporaries. It seems fitting for us to follow Tawney’s tradition as we emerge from a pandemic era that brought economic, social, and environmental challenges to the fore. Now is the time to recommit ourselves to structuring businesses and institutions that actively facilitate human flourishing.

REALIZING HUMAN FLOURISHING

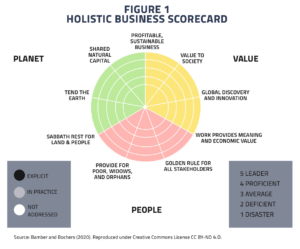

The contemporary conception of common good business has further developed Tawney’s early faith-informed view; this development includes guidelines for practical application. Two recent frameworks for practical application borrow from the balanced scorecard22 and triple bottom line (people, planet, profits)23 to construct new tools: the Quadruple Bottom Line framework24 and the Holistic Business Scorecard.25 Will Oliver’s quadruple bottom line model adds “praising God” to the more familiar triple bottom line. Joseph Bamber and Andy Bochers’ holistic scorecard also draws up- on the triple bottom line, seeking to operationalize the concepts of wellness and redemption discussed in the common good conception of business without using the terms shalom and flourishing. Indeed, their application of George Ladd’s “kingdom as a present gift”26 bears a resemblance to Tawney’s functional society. This article focuses on the holistic scorecard in the interest of brevity.

The Holistic Business Scorecard consists of three categories of measurement: caring for people, tending to the earth, and creating value. Each category is divided into sub-categories that define the category and more readily lend themselves to assessment.

- Caring for people: work provides sacred meaning and value; the Golden Rule as applied to customers, employees, and stakeholders; provide for the poor, widows, and orphans.

- Tending to the earth: sabbath rest for land and people; tend the earth/natural environment; the earth is the Lord’s (natural capital shared by/for all).

- Creating value: profitable, sustainable business; value to society; global discovery/innovation.

These elements are organized into a spider diagram (Figure 1) for graphically assessing the degree to which a business is achieving or addressing each measure. Importantly, Bamber and Borchers note that the goal is not perfection in any category but rather balance and identifying growth opportunities.

The good news is that companies small and large are striving to operate as common good businesses and actively facilitate human flourishing. Some excel at caring for people, others tending to the earth or creating sustainable value. All are actively seeking creative ways to help realize what R. H. Tawney would have referred to as a functional society.

HOWDY HOMEMADE ICE CREAM

Tom Landis opened his first Howdy Homemade Ice Cream store in Dallas, Texas, in 2015.27 Tom had prior success in the restaurant business but imagined and designed the Howdy concept for a different purpose. His goal was not simply to make money selling good, original ice cream (they do) but to create a business that could be staffed and run by neurodivergent employees such as those with Down syndrome or on the autism spectrum. Landis’ experience as a restaurateur taught him that positive customer experience is crucial to success and difficult to deliver. Exceptionally high employee turnover rates, fierce competition among restaurants for qualified staff, and constant hiring and training of new staff present were persistent challenges. Tom also recognized an untapped pool of potential employees gifted in welcoming strangers and making people happy who are eager to learn and want meaningful work. Howdy Homemade is organized to hire, develop, and run each store with a predominantly neurodivergent workforce. “It is a business about people first, then the food” says Landis. “We want our ice cream to be as good as our people.”28

Tom’s business model prioritizes caring for people by designing his business to provide work and a career path for neurodivergent people, an often marginalized group in our society. The relationships Howdy Homemade has built go far beyond those with his employees. The COVID-19 pandemic affected Howdy Homemade as it did most other service-industry businesses, placing Landis’ business model at risk in late 2020. By September 2020, the outlook for Howdy Homemade was not good, but the community stepped in by raising over $100,000 through a GoFundMe page. This was enough to keep the enterprise going and invest in an ice cream truck that serves Howdy Homemade treats in a socially distanced manner.29 As Tom Landis said in a recent interview, “It’s no longer our restaurant. It is truly the city of Dallas’ restaurant.”30 And now the company is expanding beyond Dallas. Howdy Homemade recently opened one of its first franchise locations in Katy, Texas.31

FIRST FRUITS

Ralph Broetje had a dream as a teenager to establish an orchard and use the profits to feed hungry children. Ralph and his wife Cheryl bought their first cherry orchard in 1968. They later sold that land and expanded into apples. In the 1980’s they saw a shift in the Central Washington seasonal workforce from predominantly local residents who were no longer interested in farm work to migrant workers, many from Mexico.

The Broetjes set out to learn more about their new workers and came to empathize with their situation: the difficulties of the migrant life, problems associated with the safety of workers and their children as they moved from farm to farm with the seasons, and their aspirations for a better life. So the Broetje’s decided to redesign and operate their business in a way that could help meet these needs. They began by modifying their business model, adding packing to growing, providing cold storage, and expanding tree fruit varieties to extend the harvest season. Ralph also experimented with new apple varieties, eventually patenting Broetje Orchard’s own variety, the Opal, a sweet and tangy apple with fruit that doesn’t brown when exposed to air. These changes meant that Broetje Orchards could offer a large number of workers full-time jobs year-round, resulting in families not being on the road all year. Their workers could establish a home. The Broetje’s soon created an onsite childcare center—very unusual in the agricultural industry—to care for children and keep them safe while parents were working. They then began building housing for their employees and families, a community named Vista Hermosa (Beautiful View) by the workers. A school was eventually established, along with a chapel, laundry, and convenience store. And now, a number of Vista Hermosa children are becoming first-generation college students.32

Like Tom Landis, Cheryl and Ralph Broetje designed their business model to care for people. They employed and improved the lives of people often marginalized in our society by creating value through the operation of financially sustainable businesses. For the Broetjes, this included innovating product lines and agricultural practices. Broetje Orchards was sold in 2019 to the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan for an undisclosed amount amid challenges related to industry consolidation, climate change, water rights, and agricultural labor shortages. The company formed to operate the orchards, FirstFruits Farms, intends to continue operating according to the values that guided the Broetjes.33

INTERFACE CARPETS

There are myriad examples of for-profit common good businesses started by followers of Jesus34, is not unique to the Christian community. Interface Carpet is a long-standing example of a company choosing a common good path. Company founder Ray Anderson and the people of Interface Carpet had no idea how they would become carbon-neutral by 2020 when they embarked upon that quest in the late 1990s. Nobody knew how to transform a business model built on oil—as a power source and raw material—to a sustainable, carbon-neutral operation. Combining internal research with partnerships throughout their supply chain, Interface and industry partners have invented new technologies and transformed their product line, meeting their 2020 goal.35

One example that both tends to the earth and cares for people is the Interface Net Effect product line. In partnership with fiber supplier Aquafil and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), Interface developed a supply chain that utilizes discarded fishing nets as the raw material for carpet tiles. The Net Effect circular supply begins in fishing villages (their first was in the Philippines), where abandoned fishing nets damage the marine ecosystem. Villagers generate supplemental income by retrieving and bundling the nets for sale. Aquafil, a major buyer of the nets, recycles the nylon into fibers and yarn used in the Net Effect carpet tile line. Importantly, the supply chain was designed to ensure that the majority of net retrieval revenue remains in the fishing villages. ZSL worked with local villagers to set up community banks which, in turn, have supported economic improvement in the village as a whole.36 The Net Effect product line is just one example of how Interface creates value through what Anderson envisioned as restorative business practices: business practices that not only stop contributing to adverse environmental and social impacts but seek to repair damage already done with the goal of restoring the environment and communities to wholeness.37

THE FUNCTIONAL SOCIETY: DESIGNING BUSINESS FOR THE COMMON GOOD

R.H. Tawney’s functional society is one in which industry prioritizes delivering products and services to society that are “necessary, useful, or beautiful, and thus bring life to body or spirit.”38 We see these qualities in the three companies profiled above. The ice cream made and served by Howdy Homemade may not be necessary, but it is certainly beautiful and brings life to body and spirit for both the community and its workforce. Broetje Orchards, now FirstFruits Farms, brings life to body and spirit by facilitating wholeness in community and family life and providing nutritious food distributed across the United States year-round through their growing and packing operations. Interface Carpets provides useful and beautiful carpet in a carbon-neutral manner. In the case of its Net Effect products, Interface does so in a fashion that restores marine life habitat and builds the economic vitality of all people in its supply chain.

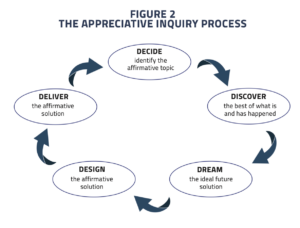

These businesses were intentionally designed or redesigned to address social and environmental needs by operating a financially sustainable business. Tawney described this as a functional approach to business: seeking to serve society rather than simply accumulating wealth. Tawney credited humanity with recognizing the social role of economic activity from time to time and celebrated actions that resulted from this recognition. He mourned, however, the generally short-lived nature of these activities often succumbed to the forces of individualism, greed, and wealth-building.39 In the early twenty-first century, we are well-positioned to resist these forces and multiply common good business efforts. In addition to myriad common good examples,40 benefit corporation legislation in many states enables companies to identify multiple stakeholders beyond shareholders in the articles of incorporation, protecting company management from shareholder lawsuits claiming inattention to share- holder interests.41 We also benefit from change leadership research42 to help us transform our companies into common good businesses. Appreciative Inquiry is one such change leadership tool.

The Appreciative Inquiry change leadership process (Figure 2) has been widely used in industry and churches.43 It is a collaborative, holistic, strengths-based model that matches well with companies aspiring to transform themselves for the common good. Appreciative Inquiry consists of five basic steps: decide on the change agenda and topic, discover what’s working today, dream about future opportunities, design what the future should be, deliver and execute the design. Ideally, all stakeholders are in the room concurrently for an Appreciative Inquiry summit: employees, management, suppliers, community members, etc. Summits have the advantage of accelerating the change process, but they are also complicated and costly to facilitate given they require pausing company operations for 1-3 days. A more workable approach for many companies may be the progressive Appreciative Inquiry, a series of 12 two to four-hour meetings that take place over several weeks or months. The downside of a progressive inquiry is that participants can miss meetings and get sidetracked over time with other priorities. Maintaining continuity is critical to the success of a progressive approach.44

DECIDE

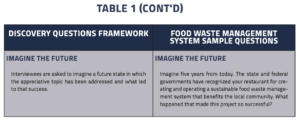

Appreciative Inquiry begins with decisions about the affirmative topic to be addressed. Affirmative topics are strategic and contribute positively to organizational effectiveness when achieved or expanded. Notably, topics are framed in the positive. Here, an organization may use the Holistic Business Scorecard discussed earlier to identify current strengths and development opportunities in the three scorecard categories. Identified development opportunities are then converted into affirmative topics. For example, perhaps a restaurant has scored itself low on “tending the earth” due to food waste going to landfill. An affirmative topic from this assessment might be “create a food waste management system that benefits the local community” rather than “reduce food waste to landfill.”46

DISCOVER

The objective of discovery is to identify the best of what’s happening now and what has happened in the past. Importantly, this strengths-based approach avoids problem analysis and focuses on eliciting positive stories about organizational strengths. These stories are gathered through stakeholder interviews using appreciative questions that elicit information about the past, present, and future. Each interview lasts about 20 minutes. Table 1 includes a generic discovery questions framework and a set of hypothetical questions using our food waste management system example.

The next step in the discovery stage is meaning-making. In this stage, participants listen to the stories generated during the interviews, then identify the root causes of organizational success and articulate the organization’s positive core—the strengths and competencies that characterize the organization at its best. The specific methods used during meaning-making will vary based on group size and Appreciative Inquiry structure (e.g., summit vs. progressive inquiry). Still, they will likely use some form of narrative analysis or the KJ method (affinity diagrams) to facilitate the process.47 Once identified, the organization’s positive core is referenced and integrated into the dream, design, and delivery stages.

DREAM

In the dream stage, participants develop a shared image of how to address the Appreciative Inquiry topic: their “dream” or most desired solution for the topic. This dream will serve as the vision or guidepost for energizing the organization in its change efforts during the delivery stage as it implements the topic solution developed during the design stage.

Like the discovery stage, the dream stage is collaborative. If stakeholders outside the organization were involved in the discovery phase, they should be involved here. If they were not involved in discovery, inviting them to make presentations on their view of the challenge will be helpful as the organization begins its dream work.48 Better yet, involving external stakeholders in the dream process will help ensure the development of a holistic dream that is more likely to be fully realized.

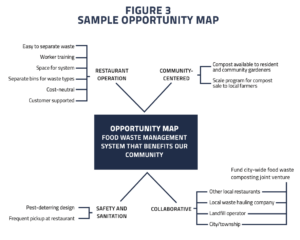

The end product of the dream stage is an opportunity map and a dream or vision statement for the topic solution (Figure 3). Both are developed collaboratively through steps that include reflection, dialogue, theme identification, and concept clarification.49

DESIGN

The human-centered design process50 is beneficial in the Appreciative Inquiry design stage. Human-centered design seeks to develop solutions that are desirable (people will want to use or buy the product or service), feasible (can be done in the relatively near future), and viable (sustainable over the long-term, including financially sustainable). The process consists of three stages: inspiration, ideation, and implementation. Organizations utilizing Appreciative Inquiry get a head-start on inspiration in the define, discovery, and dream work already completed, enabling them to quickly move into the ideation and implementation (prototype testing) phases of design. Ideation may include developing “provocative propositions,” affirmatively worded statements that capture the ideal intentions of the solutions to be tested and developed.51 Prototypes should be checked against the opportunity map and vision statements developed in the dream stage to ensure solutions meet stakeholder needs.

DELIVER

Scaling and implementing the selected prototype is a matter of effective project management and leadership. Continuing leadership of the change process will be just as crucial as solution implementation in this stage. John Kotter’s eight-stage change leadership process is an often-referenced model and can be helpful here.52 The first four stages of Kotter’s model are embedded in the Appreciative Inquiry process.53 Keeping Kotter’s last four stages front-of-mind during delivery will help ensure effective implementation and lasting success: empowering broad-based action, generating short-term wins, consolidating gains and producing more change, and anchoring new approaches in the organizational culture. It is important to remember that many organizational change efforts fail not due to the solution quality but rather the failure to engage the organization and stakeholders in the change process.

CONCLUSIONS

Whether designing a common good business from scratch or transforming an existing business using Appreciative Inquiry or another change leadership process, it is essential that moral, faith-informed principles and voices guide our common good business design efforts. Our endeavors to create a functional, more just society will be incomplete if they are independent of understanding human flourishing and God’s shalom.54 R. H. Tawney argued that the inherent value and importance of the human person guide the United Kingdom’s economic reconstruction following World War I and the influenza pandemic of 1918-20. Industry’s primary purpose should be facilitating human flourishing. Tawney played an essential role in advocating the moral dimensions of economic life even if his proposed solutions were not embraced.55 Christian businesspeople have a similar role today in speaking to the moral elements of business. Speaking and living God’s shalom as followers of Jesus, combined with the resources, tools, and examples discussed herein, will help us avoid succumbing to the temptations of individualism. The effort would enrich life and spirit of our fellow image-bearers by delivering products and services that are necessary, useful, beautiful.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

RICHARD H. JONSEN is Lecturer in the Rohrer College of Business at Rowan University in Glassboro, NJ. He transitioned to higher education in 2009 following a 19-year career leading change management, talent acquisition, and people development strategy in the consumer electronics, medical device, and pharmaceutical industries. This included work in the United States and Scotland. Rick received his undergraduate degree from San Francisco State University, his master’s from the University of San Francisco, and his Ph.D. from Eastern University. He has presented at the Academy of Management and Christian Business Faculty Association annual conferences. The Journal of Management Spirituality and Religion and the Journal for Biblical Integration in Business have published his written work.

NOTES

1Scott Green, “A Look at the Causes, Impact and Future of the Sar- banes-Oxley Act,” The Journal of International Business and Law 3(1) (2004), 33-51.

2Gary Hamel, “Moon Shots for Management,” Harvard Business Re- view 87(2) (2009), 91-98.

3R. H. Tawney, The Acquisitive Society (New York, NY: Harcourt Brace, 1920).

4Tawney, The Acquisitive Society.

5R. H. Tawney, Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (New York, New York: Harcourt Brace, 1926).

6Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, 29.

7Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, 8.

8Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, 183.

9Lawrence Goldman, The Life of R. H. Tawney: Socialism and History (New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

10R. H. Tawney, R. H. Tawney’s Commonplace Book, editors J. M. Winter and D. M. Joslin (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1972).

11R. H. Tawney, R. H. Tawney’s Commonplace Book, 54, emphasis in original.

12Ronald F. Youngblood, “Peace,” In The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Volume 3: K-P, 4th Edition, eds. Geoffrey W. Bromiley, Everett F. Harrison, Roland K. Harrison, Wiliam Sanford LaSor, Lawrence T. Geraty and Edgar W. Smith Jr. (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1986), 731-733.

13Youngblood.

14Nathan D. Shannon, Shalom and the Ethics of Belief: Nicholas Wolterstorff’s Theory of Situated Rationality (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2015).

15Michael E. Cafferky, “Toward a Biblical Theology of Efficiency,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business 16(2) (2013), 48.

16Shannon. Wolterstorff’s conception of shalom and flourishing are used by Jeff Van Duzer, and Kenman Wong and Scott Rae in their common good conceptions of business. Jeff Van Duzer, Why Business Matters to God (and What Still Needs to be Fixed) (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2010). Kenman L. Wong and Scott B. Rae, Business for the Common Good: A Christian Vision for the Marketplace (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2011).

17Shannon, 90.

18Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, 8.

19See for a review: Richard Harvey Jonsen, “Strategic Person and Organization Development: Implications of Imago Dei for Contemporary Human Resource Management,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business 20(1) (2017), 8-23. Reviewed scholarship includes: Helen J. Alford and Michael J. Naughton, Managing as if Faith Mattered: Christian Social Principles in the Modern Organization (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2001); Bruno Dyck, Management and the Gospel: Luke’s Radical Message for the First and Twenty-First Centuries (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan 2013); Alejo José G. Sison and Joan Fontrodona, “The Common Good of the Firm in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition,” Business Ethics Quarterly, 22(2) (2012), 211-246; Van Duzer; Wong and Rae.

20For a discussion of personal Christian stewardship in capitalist societies see: James Halteman, The Clashing Worlds of Economics and Faith, 2nd edition (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2007/1995); Ronald J. Sider, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger: Moving from Affluence to Generosity, 6th edition (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2015); Nick Spencer, Robert White and Virginia Vroblesky, Christianity, Climate Change, and Sustainable Living (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2009).

21Jonsen, p. 13. Michael E. Cafferky, “Redemption,” Christian Business Review 6(1) (2017), 18-23. David Miller & Timothy Ewest, “Redeeming Business Through Stewardship,” Christian Business Review 6(1) (2017), 24-29.

22Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, 1996).

23John Elkington, Cannibals with forks: The Triple Bottom Line of Sus- tainability (Gabriola Island: New Society Publishers, 1998).

24Will Oliver, “The Quadruple Bottomline,” Christian Business Review 9(1) (2020), 52-60.

25Joseph Bamber and Andy Bochers, “Revisiting the Purpose of Business,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business 23(1) (2020), 47- 57.

26George Eldon Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rap- ids, MI: Eerdmans, 1974), p. 72.

27Cheryl Hall, “Tom Landis and His Special Needs ‘Peeps’ Pick Up Steam With Howdy Homemade Ice Cream,” The Dallas Morning News, October 7, 2018, https:/www.dallasnews.com/busi- ness/2018/10/07/tom-landis-and-his-special-needs-peeps-pick- up-steam-with-howdy-homemade-ice-cream/.

28Texas Country Reporter, “Howdy Homemade,” YouTube video, 5:30, April 4, 2016, https:/youtu.be/w9QLM_1KW1s.

29Jake Lourim, “Ice-cream Store with Special-needs Employees Overcomes Pandemic’s Business Obstacles,” The Washington Post, October 29, 2020, https:/www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/10/29/howdy-homemade-ice-cream-pandemic/.

30Today, “Ice Cream Shop Hiring those with Special Needs Gets Surprise Grant,” Today video, 7:45, December 30, 2020, https:/www. today.com/video/ice-cream-shop-hiring-those-with-special- needs-gets-surprise-grant-93518405561.

31KTRK-TV, “Traetha Truth’s ‘Howdy Homemade Ice Cream’ Opens in Katy, Employing Adults with Special Needs,” ABC 13 Eyewitness News, July 25, 2021, https:/abc13.com/traetha-truth- howdy-homemade-ice-cream-special-needs-houston-activist/10903601/.

32Cheryl Broetje, “Shaping Workers: Calling, Valuing, Training & Empowering – Cheryl Broetje,” YouTube video, 14:52, January 25, 2015, https:/youtu.be/Me11A3NNV9Q. FirstFruits Farms, “Our Story: Bearing Fruit That Will Last,” FirstFruits Farms, 2021, https:/first- fruits.com/our-story/

33FirstFruits Farms

34See, for example, the growing number of companies featured in Seattle Pacific University’s Faith & Company film series: https:/ faithandco.spu.edu/films.

35Ray C. Anderson and Robin White, Confessions of a Radical Industrialist: Profits, People, Purpose – Doing Business by Respecting the Earth (New York NY: St. Martin’s, 2009).

36Interface, “Networks: Turning Waste Nets into Carpets,” YouTube video, 4:23, September 8, 2014, https:/youtu.be/DX6Uidpg3VM.

37Anderson & White.

38Tawney, The Acquisitive Society, 8.

39Tawney, The Acquisitive Society.

40See endnote 34.

41Note that publicly held companies may make use of benefit corporation laws that provide an incorporation framework explicitly identifying stakeholders with an interest in the company, protecting management from shareholder lawsuits claiming inattention to shareholder interests. For more information about benefit corporations: https:/benefitcorp.net/what-is-a-benefit-corporation. For a directory of Certified B Corporations: https:/bcorporation.net/ directory. While benefit corporation law does not integrate all elements of common good business from a Christian perspective, it can be a helpful place to begin. See Richard Harvey Jonsen, “Other Constituency Theories and Firm Governance: Is the Benefit Corporation Sufficient?,” Journal of Management, Spirituality, and Religion, 13(4) (2016), 288-303.

42Jeroen Stouten, Denise M. Rousseau, and David de Cremer, “Successful Organizational Change: Integrating the Management Practice and Scholarly Literatures,” Academy of Management Annals, 12(2) (2018), 752–788.

43Diana Whitney and Amanda Trosten-Bloom, The Power of Appreciative Inquiry: A Practical Guide to Positive Change (San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler, 2010). Mark Lau Branson, Memories, Hopes, and Conversations: Appreciative Inquiry, Missional Engagement, and Congregational Change (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016).

44Whitney and Trosten-Bloom.

45Based on Whitney and Trosten-Bloom; and Bernard J. Mohr and Jane Magruder Watkins, The Essentials of Appreciative Inquiry: A Roadmap for Creating Positive Futures (Waltham, MA: Pegasus Communications, 2002).

46The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals may also be useful as a reference during the decide stage. https:/sdgs.un.org/ goals.

47See Whitney and Trosten-Bloom, Mohr and Watkins, and Branson for method discussions and examples. For an early discussion of affinity diagrams (KJ method) see Raymond Scupin, “The KJ method: A technique for analyzing data derived from Japanese ethnology,” Human Organization, 56(2) (1997), 233-237.

48Gina Hinrichs and Jim Ludema, “AI in Business Renewal: Turning Around a Manufacturing Division at John Deere,” David Cooperider and Associates, 2012, https:/www.davidcooperrider.com/wp-con- tent/uploads/2011/11/John-Deere-Case3-1x.pdf.

49See Whitney and Trosten-Bloom for a helpful discussion of this process.

50Tim Brown and Barry Katz, Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation (New York NY: HarperCollins, 2019). This entrepreneurship text includes a helpful chapter-length summary of design thinking: Heidi M. Neck, Christopher P. Neck, and Emma L. Murray, Entrepreneurship: The Practice and Mindset, 2nd ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2021). The IDEO. org Field Guide provides helpful design thinking tools and guidance: IDEO.org, The Field Gude to Human-Centered Design (Palo Alto, CA: IDEO.org, 2015) https:/www.designkit.org/resources/1.

51Whitney and Trosten-Bloom, 204-205.

52John Kotter, Leading Change (Boston, MA: Harvard Business Re- view Press, 2012).

53Stouten, Rousseau, and de Cremer.

54Michael E. Cafferky, “Sabbath: The Theological Roots of Sustain- able Development,” Journal of Biblical Integration in Business, 18(1) (2015), 35-47.

55Tim Rogan, The Moral Economists: R. H. Tawney, Karl Polanyi, E. P. Thompson, and the Critique of Capitalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017).